It is claimed that the Viking exploration of North America was one of the great achievements in human history. And that statement may very well be true. So I wanted to know Viking origin. In the pre-Copernican Age, the dark mystery of the Atlantic Ocean was well known to lead mariners to certain death from sea monsters that existed along the edge of the flat world. So why did the Norsemen relentlessly push their boats across a bleak, ocean waste toward the horizon’s edge for certain hardship and misfortune?

***

The Norse had notorious war galleys, known as Longships, which were swift and maneuverable, ideal for quick hit-and-run raids in sea harbors and waterways of Europe. These raiding expeditions were known as “going-a-Viking,” and because of that phrase the Norse were feared throughout Europe. But the Norsemen who sailed their way to Newfoundland were not fierce raiders like the Danes. The Norse’s expansion across the Atlantic was another step for their livestock farmers to take part in the same development that was happening throughout the British Isles, Iceland, Greenland, and then Vinland.

Norse interest to trek into the North Atlantic occurred from AD 800 through AD 1000. Their expeditions may have been caused by population pressures and political unrest in the Norse homeland. It seemed probable that the Norsemen left their homeland to find a place where their customs and freedoms were not threatened.

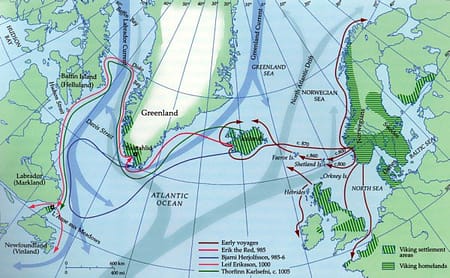

The Norse occupied the Shetlands, Faroes, and Orkneys by AD 800 and by AD 860, the Norse discovered Iceland. They settled Iceland by AD 874 and fully occupied it by AD 930. The occupation of Iceland was so rapid that after a short time, the island felt the pressures of overpopulation. By AD 975, a massive famine struck, which increased their interest to search for new lands to relocate and remain strong. They heard rumors of land to the west, possibly spread by previous Irish voyages that led Erik the Red to discover Greenland in AD 982.

In the North Atlantic, the Norse did not utilize the typical Longships that were employed in Europe, but used vessels constructed to withstand hardship, strain, and exposure to the sea. These vessels were known as Knarrs, and they were specifically suited for carrying cargo. Knarrs were also open to the elements and, although driven by sail, it was small enough to be rowed. Most knarrs were built in Europe and exported to Greenland, and this made Greenland dependent on secure trade links with Europe.

The people of Iceland and Greenland subsisted on livestock, farming, and trade. These regions were not suitable for growing grain. They raised sheep and goats, which dominated their agricultural economy. The impact on this region from large numbers of settlers, livestock, soil damage, and the felling of trees caused the decline of the environment. It was quite probable that these impacts were one of the reasons why the Norse found it necessary to venture out on the North Atlantic and sail west in AD 1000.

- Post Contents -

NORSE PROFILES AND NORTH AMERICAN FOOTPRINTS

Erik the Red

Several medieval Icelandic sources, specifically The Saga of the Greenlanders, The Saga of Erik the Red, The Book of Icelanders, The Book of Settlements, The Saga of Olaf Tryggvason, and The Saga of the People of Eyri, recorded common details of Erik the Red’s life though slight variations existed between them. The overall view of Erik by historians was that he was an important historical person.

Erik Thorvaldsson was born in Rogaland, Norway in AD 950. He was the son of Thorvald Asvaldson (also spelled Osvaldson). and later was known as Erik the Red because of his red hair and beard. When he reached the age of ten, Erik left with his father – who was exiled from Norway after he killed someone – and they settled in Dranga, Iceland. After his father’s death, Erik married Thorhild, a woman from a wealthy family. Erik inherited a large farm north of Dranga, and there he cleared land and built a home called Erikstad. In AD 970, his son, Leif, was born and who would become another famous Norse explorer.

Around 982, an unexpected landslide destroyed the dwelling of Erik’s neighbor, and the cause was found to have come from an accident by Erik’s servants. Enraged, the neighbor sought retribution against Erik by killing his servants. Erik wasted no time and avenged his servants’ deaths by killing his neighbor.

Erik was then outlawed from Haukadalur because of the killing. He then claimed the islands Brokey and Oxney, and farmed at Tradir on Sudurey Island the first winter. Thorgest, someone Erik knew, asked to borrow Erik’s bedstead boards and Erik lent them to him. Sometime later, Erik moved to Oxney where he farmed at Eiriksstadir. Erik then wanted his bedstead boards back and when he found Thorgest, he would not return them. Erik went directly to Thorgest’s dwelling and took the boards. Thorgest came after him. They fought each other near the farm at Drangar where two of Thorgest’s sons were slain, including several other men.

Erik and his companions were sentenced as outlaws at the Thorsnes Assembly. Erik went on trial and was found guilty of murder. He was once again banished from his home. Immediately, Erik was relocated by his friends to a hideout where he made a ship ready to sail. Meanwhile, Thorgest and his men searched the islands for him. Finally, the ship was ready and Erik and his men slipped away around the islands. Erik could not return to Norway, so he had to look for the land to the west he heard described by an Icelandic settler, Gunnbjorn Ulfsson.

Erik was having no luck until his ship was driven off course by a sudden weather system of strong winds that changed their direction. After the storm, they found the ship had sailed further westward and there before them was unfamiliar land – Greenland. He spent three years (982-985) exploring the coasts of Greenland.

After his exile ended, Erik returned to Breidafjordur and declared he wanted to settle in the new land permanently. He named the land Greenland, and it was a fitting name for the chosen areas of settlement because the areas were a noticeably green contrast to the otherwise barren landscape. The Saga of the Greenlanders and The Book of Settlements coincided over the 14 ships that made it to the new area. Since the sources placed the voyages 14 or 15 winters prior to Iceland becoming Christianized – an event known to have taken place in AD 999 or 1000 – the dates for the 14 ship expedition were either AD 984 or 985. Archaeological evidence confirmed the Norse settled southern Greenland around this time. The Saga of the Greenlanders mentioned nine settlers and the land given to them by Erik. Most likely, they were livestock farmers raising cattle, sheep, and goats.

Later in life, Erik gained considerable status when he gained full recognition as the highest chief of Greenland. The Saga of Erik the Red stated, “he was held in the highest esteem, and everybody referred to his authority.” The year and cause of Erik’s demise remains unclear. The Saga of the Greenlanders mentioned he died the winter after his son Leif’s return from Vinland (AD 1000) during an epidemic at Brattahlid. According to the Saga of Erik the Red, Erik was still alive in the eleventh century after the epidemic and when explorer Karlsefni sailed to Vinland.

There are few mentions of Erik the Red’s characteristics in the sagas, but his exploits made his personality apparent – headstrong and quick-tempered, with a mindset for status and influence as well as improving his destiny. After a failed defense in the Icelandic court of law, he grabbed the opportunity to venture west out to sea and seek new land unknown to the Europeans. He succeeded in settling and developing the new land, which still carries the name he gave it, Greenland.

Bjarni Herjólfsson

According to the sagas, Bjarni Herjólfsson had set sail from Iceland to Greenland in AD 986 when he was blown off course by a relentless storm. After the storm, he found his ship off an unfamiliar shore. It was not his intended destination because it didn’t look like anything he was told. It was too forested. He had no map or compass and he wasn’t certain of the location of Greenland. He was looking for a Norse colony where he was told his father had gone with Erik the Red to resettle in Greenland, and he was sure he was too far south. He turned his boat and headed north. During his journey north, Bjarni recorded various landscapes of wooded hills to flat, forested coastlines, and glaciated mountains. A week later, he arrived in Greenland.

According to the Grœnlendinga saga, Bjarni Herjólfsson was an experienced pilot who intended to follow his father from Iceland to Greenland:

“Then Bjarni said, ‘This voyage of ours will be considered foolhardy, for not one of us has ever sailed the Greenland Sea.'”

Grœnlendinga saga continued the story that they had gone to sea as soon as they were ready. They sailed for three days and watched land disappear below the horizon, lost from sight. The fair wind stopped and soon the northerly winds set in along with a heavy fog. For days they struggled to determine their course, then finally the sun reappeared and they were able to get their bearings again. They quickly hoisted sail and after a day’s travel they sighted land. They discussed what land this might be and Bjarni thought it might be Greenland since the land was not mountainous, but wooded and with low hills. They continued their journey and after sailing for two days, they once again sighted land. They brought their ship close to the shore and saw that it was flat and wooded. They turned the boat out to sea again and sailed in front of a south-west wind for three days before sighting another land. This one was high and mountainous, and topped with a glacier. They continued to follow the coastline and discovered it to be an island. Again, they sailed out to sea with the same fair wind, and traveled for four days until another land was sighted.

“This tallies most closely with what I have been told about Greenland,’ replied Bjarni. “And here we shall go in to land.” The Vinland Sagas 1965:52–54

Bjarni was a merchant and his primary interest was trading with established settlements. He was not interested in risky investments or speculative efforts in organizing new ones; therefore, he had no intention to return to his discovery. Even the Greenland colonists were not motivated to take their own action and return to the new discovery right away because they were still in progress of organizing their new settlement. There was no return trip for almost a decade.

Leif Eriksson

In AD 1000, either by accident – according to the Karlsefni Saga – or with forethought – AD 1002, according to the Saga of the Greenlanders – Leif Eriksson (Leifur Eiriksson), son of Greenland leader Erik the Red, took special interest in Bjarni’s stories of the unfamiliar land with woodlands after he returned from his sailing journey that went astray. Leif then bought the ship that Bjarni had used and set out with a crew of 35 seamen to retrace Bjarni’s route in reverse to find and explore the new land with woodlands – North America.

Leif named the regions as he traveled southward. First was Helluland – named flatstone land with forbidding mountains and glaciers. Then he sailed south and went ashore on a sandy beach with woodlands he called Markland (forestland). He continued further south, and his boat came upon land “so choice, it seemed to them that none of the cattle would require fodder for the winter. Salmon in the river and lake…bigger than they had ever seen before,” and so were the wild grapes. He named the place, Vinland (wineland). Leif and his men built typical Norse dwellings made of sod walls and peaked roofs of timber and sod. They wintered there.

Most historians agreed that Helluland was Baffin Island and Markland was Labrador. Vinland has not been positively identified, though some speculated it may be the Island of Newfoundland.

Thorvald Eriksson

Thorvald Eriksson, Leif’s brother, also ventured to the unknown mainland and explored further into the new continent from AD 1004 to 1007 using Leif’s base of operations in Vinland. It was recorded that at a certain headland, he and his party encountered “three skin boats…and three men under each.” From saga descriptions, it was not possible to confirm whether the Skraelings (old Norse) were Indians or Inuit. Eight of the Skraelings were killed except one. He escaped. More Skraelings returned and attacked the Norsemen, killing Thorvald with an arrow.

Thorstein Eriksson

A second brother, Thorstein Eriksson, launched another effort in AD 1008 to locate Vinland with his wife Gudrid and bring back his brother’s body. Unfortunately, they spent much of the summer fighting turbulent winds and seas. Finally, they gave up and sailed back to Greenland. Just before winter, Thorstein and his crew arrived at Lysufiord in Greenland, which was a western settlement where they spent the winter with friendly inhabitants. During that winter, a widespread sickness afflicted the inhabitants of the settlement, killing Thorstein and several others.

Thorfinn Karlsefni

Another ambitious effort was led by Thorfinn Karlsefni, who was born Thorfinn Thordarson (~AD 980 to 995). He was an Icelandic explorer and chief leader of the medieval expedition for North America’s colonization from AD 1002 through 1007. He has been referred to by his nickname, Karlsefni, which means “the makings of a man.” Karlsefni appeared in several historical sources – specifically, a long passage in The Saga of the Greenlanders that was devoted to him, chief subject in The Saga of Erik the Red, and The Saga of Thorfinn Karlsefne. There are also short accounts in the Old Norse manuscripts known as the Arni Magnusson codex 770b and Vellum codex No. 192.

An Icelandic aristocrat and wealthy merchant ship owner, Karlsefni acquired his wealth from a share in an ocean-going, commerce ship trading merchandise between Iceland and Norway. He extended his trading reach to Greenland where he made port at Erik the Red’s settlement, Brattahlid, with his business partner, Snorri Thorbrandsson, a crew of 40 seamen, and a ship loaded with goods. They wintered with Erik the Red and Karlsefni grew captivated by Gudrid – Thorstein’s widow – who was also a native to Iceland and noted for her beauty and intelligence. Erik gave Thorfinn permission to wed Gudrid – from The Saga of Erik the Red – and Erik’s son Leif – The Saga of the Greenlanders – had the wedding take place at Brattahlid.

There was much discussion among the men about the importance of the natural resources on Vinland; the self-sown wheat, wild grapes, lumber, and burl wood (mösurr – Old Norse), which the Norse prized for its intricate ring patterns. Since Leif Eriksson had already explored it, they urged Karlsefni to make the journey.

Karlsefni organized three vessels with 140 seafarers and some women, including Gudrid and Freydis (daughter of Erik the Red [The Saga of the Greenlanders differed from The Saga of Erik the Red regarding the Freydis expeditions]), as well as ample livestock and sailed northwest to Vesterbygd or “Western Settlement” of Greenland to Bear Island, then south till they reached the land called Helluland (Baffin Island) with its great flat slabs of stone. They sailed further southward to a land thickly wooded they called Markland (Labrador). After the first winter, the voyagers divided into two groups. One went north and the other, led by Karlsefni, headed south.

Karlsefni and his companions settled in L’Anse aux Meadows and built dwellings at the northern tip of Newfoundland. The settlement was positioned alongside an oval formed beach protected by headlands and islands. A water stream moved down to the bay and salmon lurked along its banks. The settlement prospered for three years and during that time, and it was recorded that Karlsefni’s wife, Gudrid, birthed a boy named Snorri – the first white child born in North America.

Karlsefni set out again with his party and they traveled for a long time. Finally, they arrived at a river that flowed from a lake into the sea. It had wide sandbars at its mouth and was impossible to enter until high tide. On the shore of this lagoon, they made camp and called it, Hóp (tidal lagoon). It was here that they saw the wheat fields and vines of Leif’s Vinland. All around them was a land of plenty. In the low-lying areas, there were fields of self‑sown wheat, animals in the forests, and wild grapes thriving on the thickets of small trees along the riverbanks. Streams were filled with fish and the Norsemen caught halibut in tidal pools. Though Hóp never became a settlement, it remained as a summer base. According to the Hauk’s Book version (1306-1308) of The Saga of Erik the Red, Karlsefni spent two summer months there with his 40 men, while the rest of the party stayed at Straumfjord (current fjord), their base camp.

The Sagas’ stories regarding Karlsefni were noteworthy for the pictorial descriptions of the meetings with the natives on the land, called Skraelings by the Norse. They came in canoes covered with animal skins and watchfully, approached closer to the Vikings on shore. Their initial encounter was peaceful; they were curious. These natives were dark complexioned with dread hair, great eyes, and broad cheeks. Both parties stood and looked at each other with surprise and interest. Some sources supported the theory that these natives were most likely ancestors of the east coast, North American indigenous peoples like the Mi’kmaq, the Beothuk, Innu, and Dorset.

The Skraelings returned in spring, this time carrying animal pelts. In exchange, the Norse offered milk or red cloth for the furs. It’s unclear as to why a fight occurred between the two parties, one source mentioned the Skraelings were terrified of a bull that belonged to the Norse and they fled. Another source described the Skraelings fixed interest in the strange iron implements the Norse possessed. They had never seen such tools before and, according to The Saga of the Greenlanders, the Skraelings may have understood the value of these tools but not how they were made. One Skraeling, as it was told, picked up a forgotten axe and struck another Skraeling, killing him. This scared the reckless Skraeling, and the axe was thrown far into the water. The Norse then refused to trade any iron tool for Skraeling goods.

A few weeks later, the Skraelings returned to fight but they were defeated. The Norsemen narrowly escaped with only two of their party slain. Karlsefni realized that although this rich land had much to offer, the Norse would be under constant fear from attacks by the indigenous people.

Karlsefni and his men returned to Straumfjord where they spent the winter. The next spring, Karlsefni set out again to revisit Hóp and stayed two months. He made an additional voyage northward in search of Thorhall, rounding Keelness and continued westward along the north coast – Cape Breton Island – then southward again until they reached the mouth of a river that flowed east to west. They spent that winter back in Straumfjord (1005-1006).

The following spring, Karlsefni’s party prepared for their return to Eriksfjord in Greenland. On their way back, the Norsemen captured two Skraeling boys from a small party encountered in Markland, where the expedition party separated. Karlsefni and his party arrived safely in Greenland with a boatload of valuable wild grapes, wood, and furs, but the other party was lost to the Irish Sea with only half the crew escaping back to Ireland in the boat.

Karlsefni’s expedition to Vinland was successful, increasing his prominence among the Norsemen. Karlsefni and Gudrid spent the following winter with Erik the Red before returning to Iceland the next summer and finally settling at his family estate, Reynisnes. The boy captives were eventually baptized and taught the Norse language in Greenland.

Though the regional names used between Karlsefni’s visit and those explored by the sons of Eric the Red were very similar, the actual geographical descriptions revealed enough differences to doubt they were in the same area. The ventures of the Eric-sons, according to a shared perspective among Norse historians, were confined along the east coast of North America; whereas, a real possibility emerged that Karlsefni may have sailed into Hudson Bay instead of coasting along Labrador or Newfoundland.

The Flatey Book narrative is a slightly different account of Karlsefni’s expedition – Thorvald Eriksson and Freydis undertook separate explorations to find Vinland; one before Karlsefni and the other after Karlsefni. Thorvald was killed on his expedition (Saga of Eric the Red [described previously]), and Freydis committing atrocities against her comrade Icelanders, Helgi and Finnbogi, which were not mentioned in the Saga of Eric the Red. Flately Book, on the other hand, mentioned domestic conflicts between the women in the colony during the third winter. It also neglected to mention the voyage of Bjarni Herjólfsson, but included Thorvald and Freydis on Karlsefni’s expedition.

VINLAND

Norwegian explorer and author, Helge Ingstad, along with his wife Anne Stine, an archaeologist, sailed the sea route outlined in the Viking sagas. Their voyage took them to a grassy location on the northernmost tip of Newfoundland called, L’Anse aux Meadows. The first excavations began in 1961 to 1968 and another from 1973 to 1976 (Williams, 1991:222). The remains of eight turf‑walled dwellings were uncovered. One of them was a longhouse with five rooms and a great hall with a “smithy“ – a place where bog iron was smelted. Several of the dwellings had stone ember pits exactly like the Norse ones found in Greenland. A soapstone spindle whorl was also unearthed, an artifact similar to those in the Norse ruins in Greenland, Iceland, and Scandinavia. The discovery of the soapstone suggested women were also present at the site, along with men. These findings were compatible with the Viking sagas.

The meadows’ soil was fertile. Fishing and hunting game were abundant. The environment was stable for crops and the climate mild. And there was iron. So was this Vinland? No one knows for certain, but the site was undoubtedly a Norse settlement from approximately AD 1000. It is the only documented Viking site in North America, and it may have been a base camp easily reached from Greenland.

The Icelandic sagas depicted Vinland as a place with a mild climate, abundant timber, salmon, and wild grapes, but not enough information was provided to pinpoint its exact location. Because of this Norse settlement, it became the prevailing thought that the Vikings were most likely the first Europeans to land on North America.

Today, L’Anse aux Meadows is a Canadian National Historic Site as well as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. There is a small museum for the artifacts unearthed in the excavations and three recreated Viking sod dwellings depicting daily Norse life.

According to Graeme Davis, author of VIKINGS IN AMERICA, from an interview on medievalists.net:

“In saying that Newfoundland is not Vinland I don’t think I have said anything that any serious scholar would disagree with. Rather Newfoundland may correspond with the Markland of the Sagas. Vinland is somewhere further south, plausibly New England, and may be a term used for a vast area of land rather than a single location.”

L’Anse aux Meadows appeared to have been a small settlement of approximately eight buildings with no more than 75 people, mostly seamen, carpenters, blacksmiths, hired hands, and possibly persons bound to a master in servitude (serfs) or slaves. It is probable that the settlement was a base camp for the repair and maintenance of Norse ships. A bloomer (iron smelting) and a smithy were identified, which confirmed where the bog iron was smelted into sponge iron, then purified for the making of nails, rivets, and other iron needs. It may also have been a base camp for expeditions further south, most likely two-thirds of the camp would have been venturing as far south as the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Various sources mentioned women were present there, as artifacts like a spindle whorl, bone needle, and small whetstones for sharpening were discovered. These were typical tools of a Norse woman’s daily work. Archaeologists agreed that this settlement was no more than a seasonal camp. It was inhabited for only a few seasons, never developing into a permanent settlement like those in Greenland. In 1997, some historians agreed that “Vinland” was not a specific site but a region that included Newfoundland and extended south into the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Why was the Norse unsuccessful settling permanently in North America? They thrived in Greenland for 500 years, yet they abandoned Vinland with its rich resources and milder climate. The sagas described voyaging as very risky for such a remote location. The Norse also met hostility from the native inhabitants.

Helge Ingstad, co-founder of the Viking site L’Ans aux Meadows along with his wife Anne Stine, commented on why the site failed to become permanent by saying that it was probable the Vikings were outnumbered by Skraelings, and that their weapons were not better than those the Skraelings possessed.

Greenland settlements in the early eleventh century were relatively new and in a pioneering phase. They did not have the population or wealth to support a new settlement in a remote location. The fragile economy in Greenland left little incentive to consider expansionism, especially to an uncharted land in North America.

According to Thomas McGovern, leading authority on Norse expansion to North America, “Greenland simply did not produce enough people or riches to act as a successful base for sustained colonization attempts, and Norse Greenlanders may have seen little immediate benefit in expending either in Vinland.” (McGovern, 285-308).

Geoffrey Scammell, British historian and educator, agreed, “The Norse had gone as far as they were going…as the settlements in Iceland and Greenland decayed they were deprived of bases, material, and incentives for any further endeavor.“

The Norse were the first Europeans to live in North America, though briefly, and their chance discovery and experience was quite limited. According to Daniel J. Boorstin, historian and writer at the University of Chicago, who said that what they did in America did not change their own or anybody else’s view of the world. What was most remarkable was that the Vikings reached America and settled there for a while, without really discovering America. It was not that the Vikings actually reached America.

THULE AND NORSE EVIDENCE IN CANADA

Evidence of Norse explorers in Canada has come from sites with iron tools or unique figurines. Their range extended from sites on the Hudson Bay to Newfoundland and further south. Mainland presence was scarce, but their arrival from Greenland is clear. Norse settlements with ample inhabitants explored lands to the north. The Thule – were the ancestors of various Inuit groups and who displaced the prior Dorset culture of the region – likely interacted more with the Vikings as their carvings indicated some form of contact with the Vikings. The Norsemen had brought to the New World the chess game for entertainment and these chess figurines became more common among the possessions the Thules left behind (McGhee, 1978:83).

The carvings in Thule archaeological sites very closely resembled them. Every Thule village excavated produced some evidence of the use of iron. Since no Native American sites in this area produced evidence for the smelting of iron, they must have obtained their iron artifacts from the Vikings. The Norse was the only foreign culture known to have this technology and to have contacted these Native Americans. The iron trade was at least partially direct, as the Vikings obtained hides and ivory, which traveled as far as China in trade (McGhee, 1978:99).

At a late Dorset site on the Hudson Bay, a copper amulet in the shape of a harpoon head was found. It was determined to be of European origin, but it was unknown if the Vikings actually traveled this far westward or whether intertribal trade brought the piece so far inland (Maxwell, 1985:244).

VIKING EVIDENCE IN WRITTEN HISTORY

Early Viking Sagas and Skaldic Epics

The primeval written sagas of the Vikings came from Iceland during the Middle Ages. It told of Norse lords, chiefs, and kings but, more importantly, the stories revealed information about Viking society; such as shipbuilding and boat wharfs, ship provisions, water barrels, sleeping arrangements, seafaring clothing, rules for women, and fleet size for attacks (i.e., against England). Ancient Scandinavian poet-singers (skaldics) passed down the epics orally from generation to generation and, still today, are considered important sources for the Viking Age.

Scandinavian Viking society, like other human societies, was built on family and social community. Their way of life was founded on family land/properties and inner solidarity. Their customs and rules of laws were unwritten but passed down orally. Their organization was a system of common war and limited royal power. In the Ansgar Biography, the usual custom was described as letting common cases be decided by the agreement of the people rather than the king’s demand.

A problem similar to Denmark and Sweden, Norway’s historical, primary sources for information regarding the ancient Viking legal system are missing. They must have referred to the medieval laws of Forstatingloven and the Gulatingloven – both Norwegian laws and in accordance to the sagas. The later Norwegian Gulatinglov was the main assembly for western and southern Norway, and its rule of law is considered the best likely model for the earliest Icelandic law, Ulvljotslovi, from approximately AD 930. So it is believed that the Gulatingl Law must be even earlier because it was initially recorded in AD 1100 to 1200. The main text of the law consisted of several chapters on boat building, navigation, and weapons.

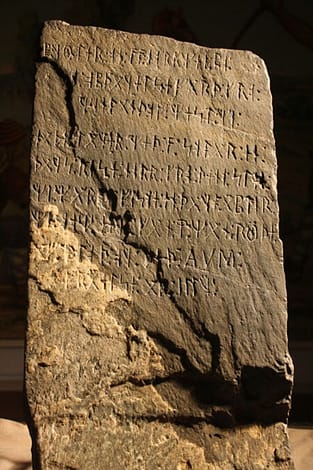

Runic Inscriptions and Foreign Sources

Runic inscriptions are the best, reliable written sources because they were usually recorded at the time of the events. Runic texts, however, were normally limited to a few lines and occurrences, lacking a definite pattern chronologically and geographically. Wooden sticks with inscribed runes were also found, but only a few survived. These sticks were once used to relay information. On 140 curious stones in Denmark, there were runic inscriptions. These stone inscriptions gave insight into the political and social conditions.

The majority of Viking sources that originated outside of Denmark were recorded simultaneously. These primary elements of foreign text sources were from annals, chronicles, biographies, and travelogues. They were originally recorded in the fifteenth century and are still considered a reliable account of earlier annal predecessors.

- Annals were chronological yearbooks of a country’s domestic and foreign policy events recorded by clerics. These annals made it possible to track Viking activity – plundering, conquests, and trade in the Christian world.

- Chronicles were written history books – Adam Bremen’s History of the Hamburg Archbishops – as well as oral accounts – Danish King Svein Estridson, Description of the Islands in the North.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles were a collection of documents about the Anglo‑Saxon history in England to AD 1154, although much of its material was from sources based on legends and stories. The chronicles also contained accounts of events not found elsewhere. Among the testimonials were tales of Viking raids and conquests of English towns.

- Biographies / Travelogues Ansgar’s Biography, written by Archbishop Rimbert, was a work on the missionary monk Ansgar and his journey to the episcopacy in Scandinavia. The work described accounts of ninth century Denmark and Sweden.

The travelogues were primarily Arab sources on the Vikings. In the tenth century, an Arab envoy met some Vikings along the River Volga. They described Viking ceremonies and rituals for chieftain burials, including slave sacrifice.

ANCIENT NORSE HISTORY

Throughout the New Stone Age, Scandinavians lived in small autonomous communities. Their region had long coastlines with many excellent harbors and fishing, including timber rich for shipbuilding. They fished, farmed, kept domestic animals, and hunted. They were born aggressive warriors and shrewd merchants, and traded as often as they invaded. These early Norse communities bred leaders who used their authority to overpower and dominate other communities. Those who became very powerful, enriched themselves further from raids and conquests overseas in foreign lands.

Most kings and jarls (or earls) of the Viking north governed from stately farmsteads. The chief business of the courts – specifically during the long winters – were centered on nightly drinking games. Scandinavian royalty possessed a limitless capacity for alcoholic liquor made from a mixture of fermented honey and water.

From the end of eighth century (AD 700) to the middle of eleventh century (AD 1000), Viking warrior ships from Scandinavian lands harassed the coasts of Europe, which was most of the known world at that time and defenseless settlements fell prey to these ruthless predators. Their invasions became fierce and endless. These Norsemen terrorized a separated Europe left defiled by Charlemagne’s Frankish Empire. Their bold and aggressive pursuits during that era became uniquely identified as the Viking Age.

The harrying of the heathen miserably destroyed God’s church in Lindisfarne by rapine and slaughter.

– Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, AD 793 –

From the Vikings beginning, these Scandinavians were the best shipbuilders and sailors in the world. They were the only sailors who could hold a course by the sun and stars; whereas, others had to keep in sight of land. They also knew precisely the high risks of shipwreck. So for four centuries, these marauders, merchants, and colonizers manned fast ships out of Scandinavia to strike Europe and western Asia with fear and dread. They left not only a reputation for savagery, but also a legacy for daring exploration as well as the respect for personal freedom.

The ability of Norse sailors and settlers to extend outward from their base in Scandinavia and explore new places across parts of Europe, Iceland, Greenland, and North America was due to their adept resourcefulness to adapt to various environments. They made bold trans-Atlantic voyages, and traveled up shallow rivers in longboats equipped with oars and sails. They had cargo-carrier boats, short and fat like a tub, that could shelter large families, goods, and animals for six or seven days at sea.

These Norsemen sailed across rough seas in ships that were vulnerable to taking on water because of an imperfect freeboard design. The distance between the waterline and the vessel’s upper deck was dangerously short, but they came anyway from the northern most reaches in ships decorated with odd carvings of horses, serpents, and dragons on their prows.

The Vikings pushed out across the water and left behind a civilization that extended from Greenland to Kiev. However, not all Vikings sought the same thing. Norwegians who ventured to Iceland, the Faroes, Orkney and the far west wanted to colonize, whereas, the Swedes who penetrated Russia, known as Varangians, were more interested in trade. It was the Danes who did most of the plundering and piracy that became the Viking legend.

Norse colonization of remote islands was a story of extraordinary success. Their settlements replaced the Picts in the Orkneys and the Shetlands. They expanded their control to the Faroes – mostly uninhabited except for some monks and their sheep – and the Isle of Man. Occupation of Ireland and Scotland began in the ninth century but it did not last, whereas, settlements away from the mainlands were found to have existed longer. Yet the Irish language adopted Norse words in commerce and their maps were marked for Viking importance, with Dublin as an early trading post that the Vikings founded.

Norse impact on the northern and western Christendom was considerable and terrifying. They fearlessly came ashore on Britain’s eastern coastal islands and plundered its settlements. They invaded England in AD 793 and slaughtered large numbers of unarmed monks and looted their sanctuaries. They ransacked libraries that preserved literary legacies of the ancient world, and what they could not carry away, they ruthlessly burned. They attacked Lindisfarne monastery and their savagery shocked the ecclesiastical world. Ireland was raided two years later.

In 635 C.E. Christian monks from the Scottish island of Iona built a priory in Lindisfarne. More than a hundred and fifty years later, in 793, Vikings from the north attacked and pillaged the monastery, but survivors managed to transport the Gospels safely to Durham, a town on the Northumbrian coast about 75 miles west of its original location.

The Lindisfarne Gospels – by Dr. Kathleen Doyle at the The British Library, and Louisa Woodville.

After the turn of the ninth century, Swedes, Danes, and Norwegians left their clans and journeyed on the North Sea and the Baltic Sea toward northern Europe and western Russia. They sailed south along the western coast of France and Spain, then around Gibraltar into the Mediterranean Sea. They traveled further north on the Norwegian Sea around Norway and Finland into the White Sea, then further west on the Atlantic Ocean past Iceland and Greenland, and over the Labrador Sea along Canada’s coast of Labrador to Vinland.

The Danes harassed the inhabitants of Frisia along the North Sea coast, raiding the same towns year after year. In AD 842, they invaded the French coast and besieged Nantes, attacking its inhabitants and slaughtering them. They plundered the inland towns of Paris, Limoges, Orleans, Tours, and Angouleme. In AD 844, Spain was invaded and the Norse attacked Seville. In AD 859, the Norse raided the cities of Nimes in southern France, and Pisa, the chief port of Tuscany, Italy.

Large numbers of settlers migrated to the Iceland colony by the end of the ninth century. There were more than 10,000 Norse Icelanders by AD 930, who farmed and fished for their own personal use as well as for consumer production of salt fish for trade. The Icelandic state was also created that same year including their government, which met for the first time. It was described as a council of important men from their community following Norwegian custom.

The Greenland Viking colony was established in the tenth century and continued until the second decade of the fifteenth century; however, during the fourteenth century its connection to Europe weakened. Its active role as a colony ended with the sailing of the last royal ship to the island in 1367. It was noted that a party of Icelanders visited the colony in 1408 and a churchman sailed there in the second decade of the fifteenth century, but no further contacts were known.

These Norsemen, though crude, established earldoms and kingdoms from the Thames to the Volga, and since left an imprint not easily forgotten through the ages. They dominated Russia and gave it its name. Five hundred years before Columbus, they crossed the Atlantic. Twentieth century aircraft over Arctic wastelands used Viking navigational principles. Even their gods have endured in our days of the week – Thursday belongs to Thor and Friday is Frigg’s day.

NORSE RELICS: HOAX OR AUTHENTIC

Over many decades, archaeology revealed various articles and apparel from everyday life during the Viking Age. Written commentaries and sagas left behind from those who encountered the Vikings – most of which were composed in Iceland from the thirteenth century – were 200 to 300 years after the events, and they provided a valuable insight for others into northern history from stories of heroic exploits, prominent families, and life in their settlements.

Archaeology also exposed the last rites of the Viking Age as a mixed pattern of cremation and burial, which commonly interred weapons, household utensils, and food with the remains. A notable man or woman would be expected to have a fully fitted ship as a final resting place. Horses, hounds, and slaves were slaughtered to accompany the dead on their last voyage, and lesser men were buried with boats. Those with no resources had graves covered by stones in an outline of a boat.

Claims of Viking presence in North America are evaluated by scientific archaeology, and potential archaeological evidence and sites in North America continue to be hopeful for confirmation of Viking landings and physical presence in North America. However, one must bear in mind that archaeological sources tend to increase over time, and the evidence and interpretations from new and existing excavation sites may change. Current technology documents sites using various techniques like GPS receivers, metal detectors, and computers (film and 3D animation) among others, and these modern technological developments are not without skeptical questions and criticism. It is important to be aware that Viking hoaxes are real and are claimed as actual archaeological evidence.

The Newport Tower

Although the North American mainland revealed many Norse relics, unfortunately, most were either counterfeit or found under highly doubtful circumstances and dismissed by historians and scientists. There’s a round stone structure called the Newport Tower in Touro Park, Newport, Rhode Island, that was rumored for many years to be a Norse relic. Its original builder is still unknown today even though there were numerous scientific tests done to eliminate some of its engaging theories, which included Norse, Scots, Chinese, and Governor Benedict Arnold. Nevertheless, its case continues to be determined.

Kensington Runestone

The Kensington Runestone – is a 202 lb. (92 kg) sandstone with Runic inscriptions dated 1362 – found by Olaf Ohman of Minnesota in 1898.

“Runes are characters from an old Scandinavian alphabet, widely used from the third to the thirteenth centuries and continuing in lesser usage throughout the next centuries.

The Kensington Runestone’s inscription, dated 1362, tells of a band of Scandinavians moored near a lake in Minnesota, who returned to camp after a day of fishing to find their comrades massacred.”

Richard Nielsen, engineer and expert on the Kensington Runestone

www.geotimes.org/jan05/NN_MNrunestone.html

When the farmer, Olaf Ohman, found the stone in 1898, many of the words and runes were unknown to linguistics experts. Furthermore, a fair number of these words are part of the modern Swedish language, which led to suggestions that the farmer carved the inscription. Recent discoveries in Sweden, however, show that all of the words represented by runes on the stone can be found in Old Swedish and were in use in the 1300s. It is highly unlikely that a nineteenth century farmer would know these words were authentic, if linguistics experts did not even know that until recently.

Richard Nielsen, engineer and expert on the Kensington Runestone

www.geotimes.org/jan05/NN_MNrunestone.html

In 2000, the Kensington Runestone Museum in Alexandria, Minnesota, asked Scott Wolter, geologist and president of American Petrographic Services in St. Paul, to perform “an autopsy” to determine when the stone runes were carved. Dick Ojakangas, geologist at the University of Minnesota in Duluth, worked with Wolter on the geological examination of the stone. The results were positive for some facts like linguistics, historic record, and geologic details, and at this point, Wolter regarded the stone as authentic. However, other scientists remained unconvinced. They wanted an accurate date of the stone, but it was felt the technology was not there yet.

The Goddard Site

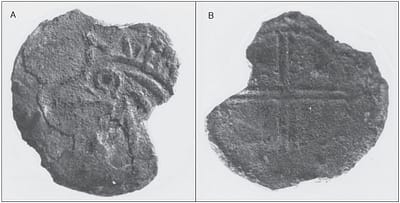

One actual artifact of Viking origin was discovered in 1957 in the United States. A Viking coin was found in Maine at the Goddard site, a prehistoric Native American site that was dated to AD 1070. The coin was determined to be the only Norse artifact found at the site.

Amateur archaeologists, Mellgren and Ed Runge, found the coin on a natural terrace about eight feet above the high tide line along with other artifacts of stone chips, knives, and fire pits on the Goddard shoreline property. The origin of the coin was initially attributed to twelfth century England, but there was no justification made as to how a medieval English coin crossed the Atlantic. Mellgren did not seek any attention for the find but, in 1978, a regional bulletin published a picture of the coin. The picture made its way to a prominent London dealer who recognized the coin immediately, and he knew the coin did not come from England. After Mellgren died, the coin’s identity became known. It was a Norse penny made between AD 1065 and 1093, and that it was made in medieval Scandinavia. It was proof that there was a Viking contact with North America before Columbus. But questions to how this small coin got to Maine have not been answered.

According to Svein H. Gullbekk, renowned numismatist at the University of Oslo and former student of coin expert Skaare, “the Norse penny cannot have originated from any recorded Norwegian hoard or single find.” In his view, the circumstantial evidence pointed to being a genuine find – even though it does not establish how the coin got to the Goddard site.

According to Bruce J. Bourque, former Maine State Museum Chief Archaeologist said it was possible the Norse penny was planted there as a hoax but, overall, the evidence strongly suggested it was an honest find.

Bourque sent the coin for a Raman spectroscopy test and remarked on its result by saying it clearly demonstrated quite strongly that the coin had laid horizontally at the site for a many, many years. The coin also showed consistent water-drip marks on it as well as more signs of it having been buried for centuries. The test was conclusive that the penny was not faked.

RECENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDINGS

The Baffin Island Debate

Content adapted from Paul Gessell’s post | January 2018.

https://artsfile.ca/ottawa-archaeologist-says-her-research-on-vikings-in-canada-being-disparaged/

In 2012, a team led by Patricia Sutherland, adjunct professor of archaeology at Memorial University in Newfoundland and a research fellow at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, found some very intriguing whetstones, while digging in the ruins of a centuries-old building on Baffin Island, far above the Arctic Circle. The whetstones, a blade-sharpening Norse tool, had noticeable wear grooves that contained traces of a bronze alloy – primarily copper and some tin. This metal element was widely used by Viking metal smiths, but its usage among the Arctic’s native inhabitants was unknown.

Sutherland’s new findings strengthened her earlier discoveries of a Viking camp on Baffin Island and her request for a further study. “While her evidence was compelling before, I find it convincing now,” said James Tuck – professor emeritus of archaeology at Memorial University in Newfoundland.

Professor Sutherland speculated groups of Viking seafarers traveled to the Canadian Arctic in search of valuable resources. During that time, walrus ivory and Arctic furs were prized by medieval aristocrats in northern Europe, and Helluland’s waters were plentiful with walrus and its coasts in Arctic fox, including smaller fur-bearing animals. The Dorset – indigenous ancestral forerunners of the Inuit people – were the hunters and trappers who could easily supply them.

Sutherland wanted to revisit the excavations in Tanfield Valley on the southeast coast of Baffin Island because she believed Viking seafarers had built a stone-and-sod dwelling there that, in the 1960s, U.S. archaeologist, Moreau Maxwell, had unearthed and found difficult to explain. Sutherland’s team cautiously excavated the remains of the Tanfield Valley ruins; unearthing pelt fragments from Old World rats, a type of shovel made of whalebone used by Vikings in Greenland to cut sod, large stones cut and shaped by a skilled person familiar with European stone masonry, and more whetstones and yarn. Stone ruins resembled Greenland Viking structures.

Unlike Sutherland, however, other Arctic researchers were unconvinced. Radiocarbon dates by earlier archaeologists already suggested Tanfield Valley was initially settled before Viking arrival to the New World. But Sutherland pointed out the site showed evidence of several occupations, and one radiocarbon date indicated the valley was inhabited in the fourteenth century. This date correlated to the same time when Vikings farmed along the coast of Greenland.

An energy dispersive spectroscopy was tasked to perform a more detailed, scientific examination of the worn grooves on the whetstones from Tanfield Valley and other sites. Microscopic lines of bronze, brass, and smelted iron clearly confirmed the influence of European metal refinement. Should Sutherland’s theory be correct, what she uncovered could open a new chapter in the history of North America.

The Norse Site Called Hóp

Content adapted from Live Science post by Owen Jarus | March 2018

https://www.livescience.com/61937-lost-viking-settlement-search.html

A Norse settlement called Hóp, recorded in Hauk’s Book version (1306-1308) of The Saga of Erik the Red, likely may be found in northeastern New Brunswick. If found, Hóp could be recognized as the second Norse settlement discovered in North America. The first being the L’Anse aux Meadows on the northern tip of Newfoundland.

Description from previous section about Karlsefni:

Karlsefni arrived at a river that flowed from a lake into the sea. It had wide sandbars at its mouth and was impossible to enter until high tide. On the shore of this lagoon, they made camp and called it, Hóp (tidal lagoon). It was here that they saw the wheat fields and vines of Leif’s Vinland. All around them was a land of plenty. In the low-lying areas, there were fields of self‑sown wheat, animals in the forests, and wild grapes thriving on the thickets of small trees along the riverbanks. Streams were filled with fish and the Norsemen caught halibut in tidal pools. Though Hóp never became a settlement, it remained as a summer base.

According to Birgitta Wallace, senior archaeologist emerita with Parks Canada who has done extensive research on the Vikings in North America, in an interview with Live Science in 2018:

“I am placing Hóp in the Miramichi-Chaleur bay area. Hóp may not be the name of just one settlement, but rather an area where the Vikings may have created multiple short-term settlements whose precise locations varied from year to year. Tales of Viking voyages were passed down orally before being written down, and Hóp may have been misunderstood as being just one site when it could have referred to several seasonal settlements.”

Brigitta Wallace continued:

“New Brunswick is the northern limit of grapes, which are not native either to Prince Edward Island or Nova Scotia.’

“Barrier sandbars occur along the coasts of [Prince Edward Island], Massachusetts and Long Island, but they are particularly dominant along the New Brunswick east coast. Wild salmon was abundant in eastern New Brunswick at the time, but research conducted by archaeologist Catherine Carlson shows that they were not found at pre-Colombian Native American sites in Maine or New England.’

“The only area on the Atlantic seaboard that accommodates all the saga criteria [for Hóp] is northeastern New Brunswick.”

DECLINE OF THE VIKINGS

After the failure in Vinland, the Viking’s world began to shrink. Viking seamanship declined. Few boats made the voyage across the Atlantic, either because of unwillingness or inability. The once thriving Greenland settlement was ultimately abandoned and it fell into decay. The isolation was fatal for the Greenlanders and, by 1500, the last Norse remnant departed or died.

The Icelanders too were eventually abandoned and were left dependent upon their own resources. But Iceland survived. In spite of its long solitude, Iceland endured to become a relic of the eleventh century. Only the Icelanders continued to speak a language Vikings would have understood. Their medieval isolation sustained the Viking culture and it was immortalized in their sagas. The Icelandic fundamental structure of their community remained unchanged until AD 1000, when Iceland’s legislative body accepted Christianity as their official religion. It was announced all should be baptized, and all were. There was no bloodshed or persecution. By the mid-eleventh century, old Norse patterns were broken throughout Scandinavia. The acceptance of Christianity by the Scandinavians was a major cause that led to end the Viking Age, as the Cross of Christ replaced the hammer of Thor everywhere.

– Comments –

While researching this post, I grew curious as to how sailing voyages in historical times were carried out on the Atlantic, and why adventuresome seamen confidently ventured out on such long-range enterprises on an ocean that was very unpredictable. What I found about the ancient achievements on the Indian Ocean – predating the Romans – trade, cultural contacts, and shipbuilding (3000 BC) quite enlightening, and many historical resources concurred antiquity was technically capable of sailing across the Atlantic, though some distant voyages may have been unintentional like ships being blown off course from heavy storms (see Norseman Bjarni Herjólfsson from a previous section).

I dug further and learned that the Atlantic Ocean’s winds and currents determined the best routes and safest sailing conditions, but an unfamiliar current on unknown waters meant going off course or entering dangerous waters. Apparently, the Vikings (or other earlier explorers) found the Atlantic Ocean’s current steady and consistent as well as the tidal current more favorable for sailing. Somehow, though, they figured out how to sail long distance with the tailwinds around the low‑pressure (rain, storms, and fronts) and high-pressure (clear skies and calm winds) systems. I also learned that cross-ocean trade winds at low latitudes were advantageous when traveling from east to west, as the westerlies were at mid-latitude if sailing from west to east. The Norse also must have determined that winds affected the waves, and large winds created large waves and, thus, dangerous sailing conditions.

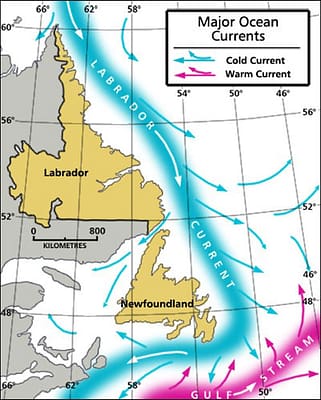

Then I wanted to know more about the North American eastern coast the Norse explored, so I found an illustration (shown) of the Labrador Current that showed a continuation of the Baffin Island Current and Flows southeastward from the Hudson Strait along the continental slope to the Tail of the Grand Banks (Smith et al., 1937). The surface ocean current flowed southward along the west side of the Labrador Sea, the route the Norse traveled along the east coasts of North America. These trade winds and drift moved the sea current in one direction along the coasts at a rate of approximately 22 miles (35 km) per day.

I also read that the Vikings learned to rely on birds, whales, the sun, moon, planets, and stars in order to help them understand how to navigate the seas and find new land. They also realized the connection between their travel experiences and multisensory observations, which gave them a greater awareness of the importance of wind, weather, wildlife, and solar time when the sun was highest in the sky.

It’s hard for me to even think about sailing the seas with no compass or radio communication, but it would make sense for the Norse to study how nature revealed itself especially if they knew how and where to look. For instance, the Vikings could hear screeching birds and waves crashing onshore; a sense of touch on the face from a sea breeze could detect wind speed and direction; their use of a plumb bob determined water depth and could also be tasted for mixtures of fresh water into sea water or vice versa; and using their sense of smell for detecting land – like plants, fire, and wet soil. Sailing through foggy and cloudy weather, however, was most unfavorable because they lost visuals of the sun, moon, and heavenly stars that guided their way. And any deviation from a planned route by only a few degrees back then would mean straying off course and a longer voyage.

Unfortunately, the Vikings only knew the concepts of north, south, east, and west, as well as the rising and setting of the sun including high noon. They didn’t know about the earth’s magnetism during their time, which is the basic function of the modern compass. Since they didn’t have seafaring charts, the Norse relied upon their medieval travelogues that were written narratives and rhymes that described foreign locations and directions.

So, considering all the information provided throughout, I would logically assume the Norse were very intelligent and carefully planned their voyages for the annual months that offered prime weather conditions for sailing. They built hardy, seaworthy ships and sailed with a warrior reputation, forging a legacy of bold exploration, adaptation, and respect for personal freedom.

– References –

Barstad, Jan. Undated. Who Built the Newport Tower? Chronognostic Research Foundation, Tempe, Arizona.

https://acmrs.org/about/online-resources/NewportTower

Bjarni Herjolfsson

http://spangenhelm.com/bjarni-herjolfsson/

Britannica Encyclopedia, Editors. Neolithic Period (New Stone Age). Recently revised and updated by John P. Rafferty, Editor. Accessed FEB2019.

https://www.britannica.com/event/Neolithic-Period

C.R.B. Theodora.com/Encyclopedia. Updated SEP2018. Thorfinn Karlsefni.

https://theodora.com/encyclopedia/t/thorfinn_karlsefni.html

Canadianmysteries.ca Bjarni Herjolfsson in “The Saga of the Greenlanders”

https://www.canadianmysteries.ca/sites/vinland/archives/chapterinbook/3876en.html

Doyle, Dr. Kathleen-at the British Library and Louisa Woodville. “The Lindisfarne Gospels,” in Smarthistory, 8 August 2015. Accessed March 2019.

https://smarthistory.org/the-lindisfarne-gospels/

Francis, C.S. 2011. The Lost Western Settlement of Greenland, 1342. MA-Thesis; California State University, Sacramento.

http://csus-dspace.calstate.edu/bitstream/handle/10211.9/1514/The%20Lost%20Western%20Settlement%20of%20Greenland,%201342.pdf

Geotimes. 2005. Geoarchaeology; Revealing a Rune Stone’s Secrets

http://www.geotimes.org/jan05/NN_MNrunestone.html

Gessell, P. 2018. Ottawa Archaeologist Says Her Research on Vikings in Canada Being Disparaged. Artsfile.

https://artsfile.ca/ottawa-archaeologist-says-her-research-on-vikings-in-canada-being-disparaged/

Goddu, A. 2015 (revised MAY2018). Nicolaus Copericus.

http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195399301/obo-9780195399301-0252.xml

Hanson, B. 2016. The Medieval Norse on Baffin Island. National Vanguard.

https://nationalvanguard.org/2016/04/the-medieval-norse-on-baffin-island/

Henriksen, L.K. Viking Ship Museum/Vikingeskibsmuseet.dk. Roskilde, Denmark

https://www.vikingeskibsmuseet.dk/en/professions/education/viking-knowledge/archaeology-and-history/written-sources-for-the-viking-age/

Hirst, K.K. 2017. Vinland Sagas – The Viking Colonization of North America.

https://www.thoughtco.com/vinland-sagas-viking-colonization-north-america-171968

Hurstwic.org. Iron Production in the Viking Age.

http://www.hurstwic.org/history/articles/manufacturing/text/bog_iron.htm

James, E., Professor. 2011. Overview: The Vikings, 800 to 1066

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/vikings/overview_vikings_01.shtml

Janzen, O. 1997. Updated AUG2004. Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Web Site Project.

https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/exploration/norse-north-atlantic.php

Jarus, O. 2018. Archaeologists Closer to Finding Lost Viking Settlement.

https://www.livescience.com/61937-lost-viking-settlement-search.html

Joanna Gyory, Arthur J. Mariano, Edward H. Ryan. “The Labrador Current.” Ocean Surface Currents.

https://oceancurrents.rsmas.miami.edu/atlantic/labrador.html

Kane, N. 2016. Spangehelm.com

http://spangenhelm.com/bjarni-herjolfsson/ see their references

Laskow, S. 2017. The Mystery of Maine’s Viking Penny.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/maine-norse-penny-archaeology-vikings-north-america

Law Manuscripts. Dan’s Topical Stamps. Medieval.

http://www.danstopicals.com/law.htm

Maxwell, Moreau S. 1985. Prehistory of the Eastern Arctic. Academic Press Inc. Orlando, FL. Pp. 244.

McCall, R. 2018. Archaeological Evidence Points to New Brunswick As Most Likely Site of Lost Viking Settlement.

https://www.iflscience.com/editors-blog/archaeological-evidence-points-to-new-brunswick-as-most-likley-site-of-lost-viking-settlement/

McGhee, Robert. 1978. Canadian Arctic PrehistoT\’. Van Nostrand Reinhold Ltd. Toronto. Pp 83, 99.

Medievalists.net. 2009. Interview with Graeme Davis-Vikings in America

http://www.medievalists.net/2009/12/interview-with-graeme-davis/

Nationalgeographic.com. 2016. Vikings in North America: A Saga’s New Chapter. Sara Parcak.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/archaeology-and-history/magazine/2016/11-12/space-archaeology-viking-settlement-excavation-canada/

New Brunswick. Where is Vinland?

https://www.canadianmysteries.ca/sites/vinland/whereisvinland/newbrunswick/indexen.html

Physics 139. 2012. The Birth of Physics – The Ancient Greeks to the Renaissance.

https://blogs.umass.edu/p139ell/2012/11/19/the-renaissance-and-the-scientific-revolution/

Pringle, H. 2012. Evidence of Viking Outpost Found in Canada. For National Geographic News.

https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2012/10/121019-viking-outpost-second-new-canada-science-sutherland/

Roberts, J.M. 1993. History of the World. Oxford University Press, New York, USA. Pp.324-25

Robinson, C.H. 1921. Medieval Sourcebook: Rimbert: Life of Anskar, the Apostle of the North, 801-865 – translated from the Vita Anskarii by Bishop Rimbert his fellow missionary and successor, (London: SPCK, 1921)

https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/anskar.asp

Sabo, D. and G. Sabo, III. 1978. A Possible Thule Carving of a Viking from Baffin Island, N.W.T. Canadian Journal of Archaeology / Journal Canadien d’Archéologie; No. 2, pp. 33-42. Canadian Archaeology Association

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23006521?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Septon, J. 1880. The Saga of Erik the Red. Translation from the original Icelandic “Eiriks saga rauoa’.

https://sagadb.org/eiriks_saga_rauda.e

Springer, K.L. 1999. The Fact and the Fiction of Vikings in America. Nebraska Anthropologist, 124. Univ. of Nebraska-Lincoln, Dept. of Anthropology

http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1123&context=nebanthro

The Columbia Encyclopedia. 1935. Columbia University Press; City of New York; pp. 1844.

The Viking Network

http://www.viking.no/

http://www.viking.no/the-viking-travels/vinland-the-vikings-in-north-america/

Thyra. 2015. The Vikings-Legal System-Survival of the Fittest

http://thyra2005.blogspot.com/2015/03/the-vikings-legal-system-survival-of.html

UBC ATSC 113 – Weather for Sailing, Flying & Snow Sports. 2016-2019 by Samantha James & Roland Stull. Last updated Feb 2019.

https://www.eoas.ubc.ca/courses/atsc113/sailing/met_concepts/09-met-winds/9g-wind-current-onwater/

Vilhjalmsson, Porsteinn. 1999. Paper given at the conference “Vestur um haf” on the sources for explorations and settlements of the Old Norse in the North Atlantic, Reykjavík, August 9-11, 1999. To be published in conference proceedings.

https://notendur.hi.is/thv/Nav_&_Viinl.htm

Wallace, B. 2006; updated MAR2015. Norse Voyages.

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/norse-voyages

Wallace, B. 2006; updated NOV2018. Karlsefni

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/karlsefni#

Wallace, B. Updated JAN2019. Erik the Red, Norwegian Explorer. Encyclopedia Britannica.

http://rmc.library.cornell.edu/exhibits/sagas/eric.html

Williams, Stephen. 1991. Fantastic Archaeology. University of Pennsylvania Press. Philadelphia, PA.

Updated 2020