Chief Pontiac was infuriated to see the schooner arrive safely at Fort Detroit, bringing needed necessities to those obstinate defenders. With renewed fierceness, Pontiac was determined to win the fort.

- Post Contents -

chief pontiac continues to blockade fort detroit – 1763

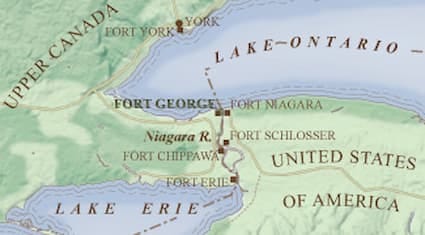

It was the 19th of June, 1763, when a rumor reached Detroit that one of the vessels had been spotted near Turkey Island, some miles from the fort. The wind slowed and the schooner dropped down with the current to wait for a more favorable wind opportunity. Several weeks before, the schooner sailed down Lake Erie to hasten the advance of Cuyler’s expected detachment to Detroit and, while on its way to Niagara, it met Cuyler’s detachment. It was there that Cuyler’s vessel remained until Cuyler and the survivors of his party returned. The catastrophic event that befell Cuyler’s captured soldiers from his detachment was being slowly relayed to the waiting vessel.

It wasn’t long before Cuyler and his remaining troops, along with a few other soldiers spared from the attack on the garrison of Niagara, returned to their vessel when they were immediately ordered to embark on the waiting schooner and make their way back to Detroit. They were almost in sight of the fort, when they found the river channel had areas that became very narrow and risky. And, unbeknownst to them, more than 800 Indians were waiting nearby to intercept their passage.

Days went by and the officers at Detroit heard nothing more from the schooner. Then on the 23rd of June, a huge ruckus was heard among the Indians nearby. Large parties were seen moving behind the fort along the outskirts of the woods. The Indians’ movements were puzzling. By evening, M. Baby arrived with intelligence that the missing schooner was trying to ascend the river when a legion of Indians came out to attack it. The garrison quickly fired two cannons to let the schooner know that the fort was still holding and protected. All the fort could do at that point was to anxiously await the boat’s outcome.

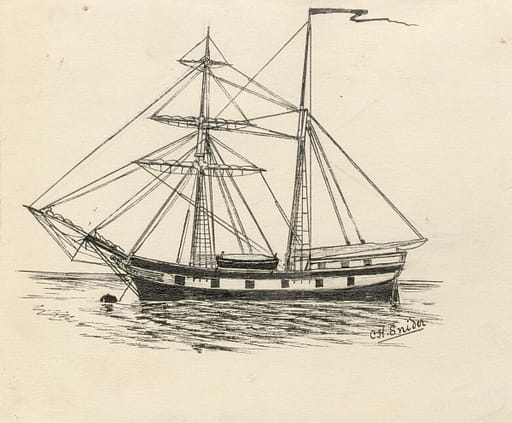

By late afternoon, a mild breeze pushed the schooner slowly upward between the main shore and the elongated border of Fighting Island. Sixty men were crowded on board with 10 or 12 men visible on deck. The rest of the men were ordered to lie hidden below and to anticipate the Indians making an open attack. As the boat reached the narrowest part of the channel, the wind disappeared and the anchor was dropped. The crew kept a strict watch. However, unknown to the occupants on the schooner, the Indians were positioned along the shore of Turkey Island behind a breastwork of logs. They were carefully concealed by bushes and within gunshot range. The Indians waited for the vessel to pass.

All was quiet during the night. The current bumped into the bow of the schooner with a monotonous splashing sound. On the wooded shores were the Indians, silently anticipating. The boat’s watchman grew concerned over suspicious moving objects on the water’s dark surface. The men below were alerted and ordered to their posts in absolute silence. The signal to fire was a blow from a hammer on the mast. The suspicious movements on the water became more obvious that they were Indian birch canoes steadily approaching their prize. Suddenly, the schooner’s darker side burst into a blaze of cannon and musketry, illuminating the night like a near strike of lightning. Musket shots flew tearing into canoes, destroying several and killing 14 Indians. Many more Indians were wounded and the rest escaped to shore (Pontiac MS.).

Recovering from their surprise, the Indians started firing upon the schooner from behind their stronghold as the boat moved further down the broad river beyond the Indian’s reach. The vessel dropped anchor.

Several days later, the vessel attempted to ascend and, this time, met with better success. Even though the Indians constantly fired at them from shore, the boat sailed on with no man hurt while leaving behind the unsafe channels of the islands. The boat slowly moved passed the Wyandot village on the way to Fort Detroit, enabling the men to send a shower of small caliber round shots that were lead or iron balls tightly packed in a canvas bag with a length of cord lashed around it, called a ‘grape.’ It looked much like a bunch of grapes and when shot, the outer cylinder was shredded by the explosion with shards and balls ejecting from its container. It expanded into a cone pattern that gave a lethal range of two to three hundred yards. Into the encampment it went, killing inhabitants and hitting others who yelped in pain and scrambled for cover as fast as they could. The schooner continued on to Fort Detroit, where it unfurled its sails and dropped anchor next to a companion vessel.

The schooner was a welcomed sight. It delivered to the garrison a greatly needed supply of men, ammunition, and provisions. It also brought important news that peace was finally concluded between England and France. It was a long, but significant war that violently unstabilized much of North America since 1755. It also left North America smoldering with dissatisfaction until the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

French Canadians become New Subjects to the British King

France ceded her claims on North America and Canada, including the lakes region to Britain. The Canadians of Detroit were also placed in a different position because of the treaty and, henceforth, were deferred as prisoners; however, their allegiance was peacefully transferred from the crown of France to the British and they became new subjects to the British king.

Many of the abandoned Canadians considered the change extremely detestable, yet they had to cordially hate the English when with them. The Canadians played their own game with the settlers and Indians by declaring the peace treaty was fake news, a lie devised by Major Gladwin. The king of France would never abandon his children, they said, and that a great French army was, at that moment, moving up the St. Lawrence River, while another was approaching from the country of the Illinois (MS. Letter – Gladwin to Amherst, July 8).

This often repeated fallacy was completely believed by the Indians. They totally accepted their Great French Father would wreak vengeance upon the arrogant and superior English, who invaded their dominion. Pontiac wholly supported this delusive hope, to the extent he became fixated on it.

Chief Pontiac was infuriated to see the schooner arrive safely at Fort Detroit, bringing the needed necessities to those obstinate defenders. He reviewed the situation with renewed fierceness and urgency. He was determined to gain possession of the fort, so he tried to terrify Gladwin into surrender by sending a message. The message urged Gladwin to yield the fort because 800 more Ojibwas were expected any day and, on their arrival, his influence would no longer prevent them from taking scalps from every Englishman in the fort. Gladwin returned a brief and contemptuous reply.

Chief Pontiac’s Council Meeting

Chief Pontiac had been anxious for a long time to gain the Canadians as contributing participants in this war, so Pontiac sent invitations to the principal Canadian inhabitants to meet him in council. At the Ottawa camp, there was a level, vacant spot that was encircled by Indian huts. Mats were spread to receive the deputies, who took their seats in a wide ring. One section was for the Canadians; whereas several of them had faces of withered, leathery features that marked them as the patriarchs of their secluded little settlement. Seated opposite them was a grim-looking Pontiac with his chiefs on each side of him and, within the circle, there was an intermediator section that was mixed with Canadians and Indians. Standing on the outside and overlooking the heads in the assembly, was a motley crowd of Indians and Canadians – half-breeds, trappers, and voyageurs appearing uncivilized in very dirty clothes.

Among the motley crowd was numerous Indian dandies, who were quite common among every aboriginal community. They held the same relative position as did their counterparts in civilized society. The dandies were wrapped in the gayest blankets, their necks adorned with beads, their cheeks daubed with vermilion, and their ears hung with fancy pendants. They stood gravely looking on, yet afraid and ashamed to take any place near the aged chiefs and warriors of distinction.

There was silence for several minutes. Then pipes were passed around from hand to hand. Finally, Chief Pontiac rose and threw down a war-belt at the feet of the Canadians.

“My brothers, how long will you suffer this bad flesh to remain upon your lands? I have told you before, and I now tell you again, that when I took up the hatchet, it was for your good. This year the English must all perish throughout Canada. The Master of Life commands it; and you, who know him better than we, wish to oppose his will. Until now I have said nothing on this matter. I have not urged you to take part with us in the war. It would have been enough had you been content to sit quiet on your mats, looking on, while we were fighting for you. But you have not done so. You call yourselves our friends, and yet you assist the English with provisions, and go about as spies among our villages. This must not continue. You must be either wholly French or wholly English. If you are French, take up that war-belt, and lift the hatchet with us; but if you are English, then we declare war upon you. My brothers, I know this is a hard thing. We are all like children of our Great Father the King of France, and it is hard to fight among brethren for the sake of dogs. But there is no choice. Look upon the belt, and let us hear your answer.”

Pontiac, MS.

Suspecting the purpose of Chief Pontiac’s council meeting, one of the Canadians brought with him a copy of the fall and surrender of Montreal, including its dependencies of which was Detroit. However, something restrained the Canadian from confessing that the Canadians were no longer children of the King of France. He decided to keep up the old delusion that a French army was on its way to win back Canada and punish the English invaders. He started his address to the council by affirming their great love for the Indians and their strong desire to aid them in the war. Then he held up the articles of surrender:

“But, my brothers, you must first untie the knot with which our Great Father, the King, has bound us. In this paper, he tells all his Canadian children to sit quiet and obey the English until he comes, because he wishes to punish his enemies himself. We dare not disobey him, for he would then be angry with us. And you, my brothers, who speak of making war upon us if we do not do as you wish, do you think you could escape his wrath, if you should raise the hatchet against his French children? He would treat you as enemies, and not as friends, and you would have to fight both English and French at once. Tell us, my brothers, what can you reply to this?”

Chief Pontiac sat silent. He was mortified and perplexed, but his purpose would not be wholly defeated.

Among the French were many infamous characters, who had no property and cared nothing of what became of them. These characters were a collection of trappers, voyageurs, and nondescript vagrants from the forest who were seated with the council, or who stood quietly looking on wearing greasy shirts, Indian leggings, and red woolen caps. Only a few of them thought it proper to adopt the garment styles and ornaments peculiar to the red man, who were their usual associates, and to appear among their comrades with painted cheeks and feathers dangling from their hair. They wanted to identify with the Indians, but these renegade whites were disliked by those of their own race as well as the savages. They were mostly a light and simple-minded crew that were not to be relied upon for strength or reliability, although some of them were tough and hard men. They were ringleaders and bullies of the voyageurs, and somewhat a terror to the Bourgeois. (This name always applied, among the Canadians of the Northwest, to the conductor of a trading party, the commander in a trading fort, or to any person in a position of authority.)

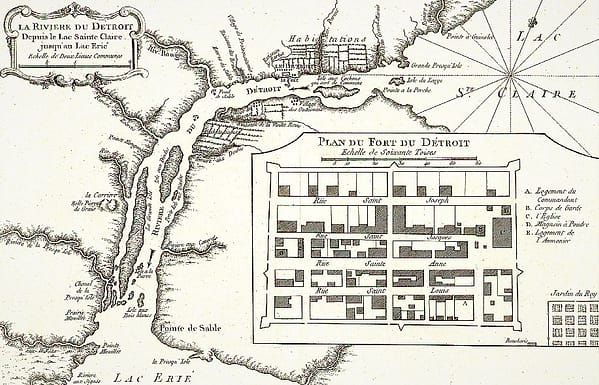

“Judge of the Conduct of the Canadians here, by the Behaviour of these few Sacres Bougres, I have mentioned; I can assure you, with much Certainty, that there are but very few in the Settlement who are not engaged with the Indians in their damn’d Design; in short, Monsieur is at the Bottom of it; we have not only convincing Proofs and Circumstances, but undeniable Proofs of it. There are four or five sensible, honest Frenchmen in the Place, who have been of a great deal of Service to us, in bringing us Intelligence and Provisions, even at the Risque of their own Lives; I hope they will be rewarded for their good Services; I hope also to see the others exalted on High, to reap the Fruits of their Labours, as soon as our Army arrives; the Discoveries we have made of their horrid villianies, are almost incredible. But to return to the Terms of Capitulation: Pondiac proposes that we should immediately give up the Garrison, lay down our Arms, as the French, their Fathers, were obliged to do, leave the Cannon, Magazines, Merchants’ Goods, and the two Vessels, and be escorted in Battoes, by the Indians, to Niagara. The Major returned Answer, that the General had not sent him there to deliver up the Fort to Indians, or anybody else; and that he would defend it whilst he had a single man to fight alongside of him. Upon this, Hostilities recommenced, since which Time, being two months, the whole Garrison, Officers, Soldiers, Merchants, and Servants, have been upon the Ramparts every Night, not one having slept in a House, except the Sick and Wounded in the Hospital.

“Our Fort is extremely large, considering our Numbers, the Stockade being above 1000 Paces in Circumference; judge what a Figure we make on the Works.”

Extract from a Letter – Detroit, July 9, 1763 (Penn. Gaz. No. 1808)

It was one of these renegades who raised the war-belt and declared that he and his comrades were ready to raise the hatchet for Chief Pontiac. The conventional Canadians were shocked and they vainly protested against it. However, Pontiac was very pleased with the addition to his forces. Pontiac and his chiefs shook hands and then with their new associates.

It was dark by the time the council ended. The renegade whites remained in the Indian camp all night, since they were afraid of the reception they would receive among the Canadian whites in the settlement. The next morning, a large feast of welcome was prepared. A large number of dogs were slaughtered and served to the guests. And according to Indian custom on such formal occasions, no one was permitted to leave until they had eaten the whole, large portion placed before them.

Chief Pontiac derived little advantage from his Canadian allies. Most of the new allies feared the resentment of the English as well as other inhabitants, so they fled before the war was over to Illinois country (Croghan, Journal. See Butler, Hist. Kentucky, 463).

The Savage Murder of Captain Campbell

The night after the feast, a party of renegade whites were joined by an equal number of Indians and they approached the fort. They entrenched themselves so they could fire upon the garrison and, at daybreak, they were observed by the garrison and the fort’s gate was opened. A file of soldiers, headed by Lieutenant Hay, suddenly charged the enemy to dislodge them. It was effective without much difficulty. The Canadians quickly fled and none were hurt, but two Indians were killed.

An English soldier who was held prisoner for several years among the Delawares learned to hate their race, while, at the same time, acquire many of their habits and practices. After the skirmish, he quickly ran forward from among Indians and knelt on the body of one of the dead savages. He quickly tore away the scalp and shook it proudly with an exultant cry to the fugitives (Pontiac, MS.). His act induced great rage among the Indians.

After overpowering the entrenched enemy, Lieutenant Hay and his men returned to the fort. Later that afternoon, about four o’clock, a man was seen running toward the fort closely pursued by Indians. As the man made it safely within gunshot range to the fort, the Indians abandoned their chase and the man rushed panting to the gate underneath the stockade. Immediately, the smaller wicket door on the closed main gate flung open to receive him. Once inside the fort, the man was verified as the commandant of Sandusky. He told of his adoption by the Indians and his reluctant marriage to an old squaw and how he seized his first opportunity to escape from her unappealing embraces.

The garrison learned through him the depressing news of Captain Campbell’s death. As an officer, he had a lofty, personal character and was held in ordinary esteem. His cruel fate angered the English in Detroit, yet there were feelings of sadness and grief as well.

The story was that the Indian who was killed at the fort and then scalped by the white prisoner that ran out that morning was the nephew to Wasson, chief of the Ojibwas. After the chief learned of his nephew’s death, the chief became enraged. He blackened his face in the sign of revenge and called together a party of his followers. They went to the house of Meloche where Captain Campbell was kept prisoner, and they seized him. They bound him to a neighboring fence where they shot him to death with arrows. Others reported Campbell was tomahawked right away, but all agree his body was mutilated in a barbarous manner. His heart was said to have been eaten by his murderers to make them courageous – a practice not uncommon among Indians, especially after killing an enemy of acknowledged bravery. Campbell’s body was thrown into the river and was later rescued and brought to shore by the Canadians, who respectfully buried his corpse. The other captive, M’Dougal, escaped (Gouin’s Account, MS.; St. Aubin’s Account, MS.; Diary of the Siege).

James MacDonald writes from Detroit on 12th of July, 1763:

“Half an hour afterward the savages carried (the body of) the man they had lost before Capt. Campbell, stripped him naked, and directly murthered him in a cruel manner, which indeed gives me pain beyond expression, and I am sure cannot miss but to affect sensibly all his acquaintances. Although he is now out of the question, I must own I never had, nor never shall have, a Friend or Acquaintance that I valued more than he. My present comfort is, that if Charity, benevolence, innocence, and integrity are a sufficient dispensation for all mankind, that entitles him to happiness in the world to come.”

Chief pontiac attacks Fort Detroit’s Armed Schooners

The armed schooners anchored opposite the fort were objects of curiosity and hostility to the Indians. The vessels caused great terror and annoyance to the attackers. These boats left their anchorage and moved to a more convenient position in order to deliver, with little effort, repeated blows to the Indian camps and villages. The Indians surveyed from shore Gladwin and several of his officers board the smaller vessel and set sail on the river. They watched the schooner tack from shore to shore in the light breeze that blew from the northwest. They were amazed at the magical power that enabled the boat to make its way against the wind and current (Penn. Gaz. No. 1808). After making a long reach from the opposite shore, the schooner came directly at Pontiac’s camp with sails swelling and masts leaning so far over till the black muzzles of her guns almost touched the river.

The Indians were surprised and fearful at the same time. They watched the schooner continue to come closer and closer until their hearts intensified so much, just with the thought, that the boat would run ashore within their murderous clutches when, suddenly, a shouted command was heard on board and her progress halted. The schooner rose upright and her sails flapped and fluttered as if tearing loose from its fastenings. Steadily the boat came round, broadside to the shore, then leaned once more to the wind and bore away fearlessly on the other tack. She did not go far.

The curious spectators were at a loss understanding the schooner’s movements. They heard a harsh rattling from her cable as the anchor dragged it out, as they watched her unroll enormous white wings. A puff of smoke discharged from her side as a thunderous blast followed, one after another, with heavy balls flying directly through the center of the Indians’ camp and tearing wildly into the forest beyond. The terrified warriors quickly scattered in every direction. The squaws grabbed their children and fled screaming. The whole encampment emptied in such haste that little damage was done, except for the destruction of their frail bark cabins (Pontiac MS.).

Similar attacks soon followed and the Indians were resolved to turn their energies toward the destruction of the boat. On the night of July 10th, the Indians sent out a burning raft that was made from two canoes secured together with rope and filled with pitch-pine, birch-bark, and various other combustibles. The Indian’s burning raft floated down the river and missed the English vessel.

All remained quiet throughout the following night, until two o’clock the next morning. It was July 12th and the sentinel on duty spotted a glowing spark of fire on the surface of the river some distance away. It gradually grew larger and brighter. The spark rose to a forked flame that burst into an inferno. Again, the schooner was spared. The Indian’s raft, which was much larger than the previous one, floated between the schooner and the fort. The fire was so bright it lit up the old palisades and the bastions of Detroit, the white Canadian farms and houses along the shore, as well as the dark edges of the forest beyond.

Standing on the shore were a group of naked spectators watching the effect of their ruse when, suddenly, a cannon released a thunderous blast that broke the stillness and before the smoke of the cannon had risen, the curious observers vanished. The raft floated down the river with its flames snapping and crackling throughout the night, until it finally landed at the water’s edge and burned to its last hissing embers as it sank into the river.

Though the Indians were defeated twice, they would not abandon their plan. Not long after the second failure, they began to build another raft. Its construction was different from the others, it was built so large that it had to be effective. Gladwin, however, had his boats moored by chains some distance above the schooners. He made other preparations for defense which were so impactful that the Indians, after working four days on their new raft, decided to give up their boat building as useless.

Meanwhile, a party of Shawanoe and Delaware Indians arrived at Detroit. They were received by the Wyandots with a salute of musketry, which alarmed the English. The progress of the war in the south and east was discussed and, after a few days, an Abenaki from Lower Canada also made an appearance, bringing to the Indians the flattering lies that their Great Father, the King of France, was at that moment advancing up the St. Lawrence River with his army. (The name of Father given to the Kings of France and England was a mere title of courtesy or policy – but the Indians never yielded to submission to any man.)

It is now two to three months since the siege of Detroit began and the Indians showed a high degree of steadiness and perseverance. Their history cannot provide another case of such a large force that persisted for so long in an attack against a fortified place. Chief Pontiac and his followers were able to keep their deep rage controlled against the English after they were told the French were soon coming to their aid. Nonetheless, it was obvious the Indians were ill qualified for such assaults. They were too cautious for an aggressive siege, and they had very little patience to work a blockade.

Wyandots and Pottawattamies beg for peace

The Wyandots and Pottawattamies had shown, from the beginning, they had less enthusiasm than the other tribes. They were now less interested than before and they didn’t want to bother with the task they were forced to undertake any longer. Thus, a deputation of Wyandots went to the fort and begged for peace, which was granted them. But when the Pottawattamies came to the fort with the same purpose, they added a preliminary request that some of their people, who were prisoners held by the English, should be released first. Gladwin, however, made his demand that the English captives known to be in their village be brought to the fort. Three of them were thereupon produced, but they were a small part of those still in captivity. The Indian deputies were sharply rebuked for their deceit and they were told to go back and return with the rest. The Pottawattamies withdrew angry and annoyed.

The following day, a new deputation of chiefs made their appearance with six prisoners. The chiefs were escorted to the council room where they were met by Gladwin and two attending officers. The English prisoners were about to be exchanged and a treaty concluded, when one of the prisoners declared there were several others still remaining in the Pottawattamie village. Immediately, the conference ended and the Indian deputies were ordered to depart. Another defeat for the Indians. This failed situation propelled them into a fit of rage that they desperately formed a quick resolution to kill Gladwin on the spot. They would figure out later how to make their escape, but, at that moment, the commandant observed an Ottawa among them. Gladwin immediately called upon the guards to seize him.

A file of soldiers entered and the chiefs saw it was impossible to carry out their plan. The Indians withdrew from the fort in a very disagreeable mood. A day or so afterward, the Indians returned with the rest of the English prisoners. Peace was then granted them and their people were set free (Diary of the Siege. Johnson MSS.) (Whatever may have been the case with the Pottawattamies, there were indications from the beginning that the Wyandots were lukewarm or even reluctant in taking part with Pontiac. As early as May 22, some of them complained that Pontiac forced them into the war.)

***

Part 4 – On Its Way

THE FIGHT OF BLOODY BRIDGE, 1763

***

References

At this point in Pontiac’s history, I decided to use Francis Parkman’s THE CONSPIRACY OF PONTIAC as my sole reference and guide for the Parts that followed Part 1. Parkman’s version gave me a much clearer window into the actual historical events, its characters, human behavior, strategies and tactics that I found dependable overall … even 200+ years later. I wanted to understand Pontiac: his character, motives, and beliefs. I wanted to know the indigenous force of the American Indian and their historical significance: their way of life, drama, ambition, and savagery. I wanted to share a story, not just an article of facts.

Parkman, Francis. THE CONSPIRACY OF PONTIAC (1851). Collier Books, New York, NY (1962).