The Treaty of Paris (10 February) ended the Anglo-French Seven Years War (French and Indian War), which secured British dominance in North America and India, while the Treaty of Hubertusberg (15 February) concluded the European War with Prussia rising as a great power in central Europe. Practically all nations involved in the war, including Great Britain, were very close to bankruptcy. However, the war set the footing for the British Empire and underpinned its maritime dominance worldwide, which lasted nearly 200 years.

France relinquished to Great Britain all claim to everything east of the Mississippi – including the port of Mobile but not the city of New Orleans and the island on which it is situated (“…provided the navigation of the Mississippi River shall be equally free, as well to the subjects of Great Britain as to those of France, in its whole breadth and length, from its source to the sea, and expressly that part which is between the said island of New Orleans and the right bank of the river, as well as the passage both in and out of its mouth…” Treaty of Paris, 1763 p.4), as well as the Caribbean islands of Granada, St. Vincent, Dominica, and Tobago, including all French forts in India. France also ceded to Britain Acadia, Cape Breton, Canada, and the St Lawrence Islands.

France retained fishery rights along the coasts of Novia Scotia and the banks of Newfoundland, and kept the Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe, Martinique, St. Lucia, as well as its trade stations in India. France also agreed to evacuate its positions in Hanover and restore Minorca to Great Britain.

Britain ceded to France the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon, and Cuba was restored to Spain in exchange for East and West Florida. Britain agreed to demolish fortifications on the Honduran coast, but the rights of her logwooders to operate in that area were specifically recognized by Spain.

The structure of society and government in both England and France were significant factors that would determine the manner in which each nation viewed colonization, as well as affecting the demands in their negotiations during the final phases of their colonial rivalry. For Great Britain, it was the commercial and manufacturing interests that were closely allied with the landed interests, whereas, this relationship between the two dominant interests in English society typically meant that state policy, when related to considerations of international commerce, was left to the masters of trade and industry (L.B. Namier, England in the Age of the American Revolution [London: Macmillan and Co., 1930] pp 33-40).

The welfare of the French state during the first half of the eighteenth century was not as closely associated with the interests of the commercial classes as it was in Great Britain, because France was dominated by a monarchy and feudal aristocracy that was saturated in luxury with a tradition of military ambition (W.L. Dorn, Competition for Empire [N.Y.; Harper and Bros., 1940] p 7). With such an aristocracy, the glory of its nation required maintenance for a great overseas empire, and its feudal military tradition demanded land expansion in North America rather than a naval development in the maritime trade (K.E., Knorr, British Colonial Theories, 1570-1850 [Toronto: Univ. of Toronto Press, 1944], pp 12-13).

Thus, a continental expansion in North America made it necessary for maintenance of armies and the erection of forts, which created enormous financial demands on the state. A debt‑ridden monarchy involved in endless struggles in Europe and with colonies in the West Indies producing big profits for the royal treasury, the West Indies were of greater importance than possessions like Canada, which ultimately drained off bullions for the sake of colonial status.

The colonies held an important position in the power relationship between Great Britain and France in the eighteenth century, and that colonial-commercial awareness was not the only factor that determined the course for colonial supremacy in the New World. Because of the rise of Prussian and Russian power during the period of 1700 through 1760, the European balance of power was in trouble and, thus, the colonial struggle between Britain and France became unstable and their wars inevitable.

- Post Contents -

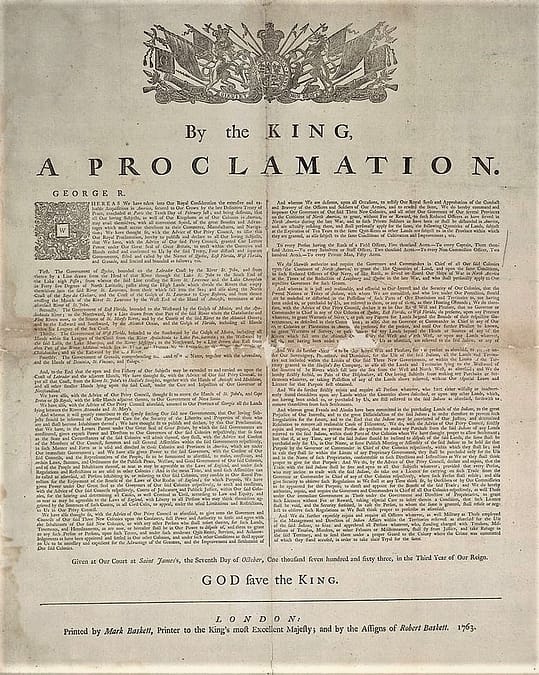

the king’s proclamation of 1763

By the King, a proclamation: George R: whereas we have taken into our royal consideration the extensive and valuable acquisitions in America, secured to our crown by the late definitive Treaty of Peace, concluded at Paris is the tenth day of February last …. We have thought fit … to erect within the countries and islands ceded and confirmed to us by the said Treaty, four distinct and separate Governments, stiled and called by the names of Quebec, East Florida, West Florida and Grenada …

Great Britain, Sovereign (1760-1820: George III | https://bac-lac.on.worldcat.org/oclc/1007612335

Bibliothèque et Archives Canada / Library and Archives Canada, 395 Wellington Collection générale / General Collection

New York Historical Society

The French and Indian War revealed an unstable frontier against inevitable Indian raids. The appointment of Sir William Johnson as Indian Commissioner in April 1755 by British General Edward Braddock was an initial step to appease the Indians. A formal and centralized Indian policy was realized when Johnson was given “the sole Management and Direction of the Affairs of the Six Nations and their Allies.” Then in the spring of 1756, Sir William Johnson was reappointed as Commissioner for the North. It was believed that land frauds were the source of Indian unrest and Johnson’s secretary, Peter Wraxall, pressed for land cessions to require approval from the Indian Commissioners.

At Johnson’s request, Wraxall prepared a sharp analysis of the Indian perspective titled, Thoughts Upon the British Indian Interest in North America. The analysis accurately assessed the Indian belief: “…our Six Nations and their Allies, … look upon the present disputes between the English and French … as a point of selfish ambition in us both and are apprehensive that which ever Nation gains their point will become their Masters not their deliverers.” Wraxall concluded that the Indians distrusted both imperial rivals that they would restore their lands to them or to even recognize the First Nations as the true ‘Proprietors of the Soil’.

(1719-1765)

In 1758, Pennsylvania and its western Indians agreed with the Treaty of Easton to make no settlements west of the Alleghenies. However, the abandonment of Fort Duquesne in November and its occupation by the British resulted in an increase of settlers that compelled Colonel Henri Bouquet to forbid settlement west of the mountains (1761). And the Earl of Egremont, Secretary of State for the Southern Dept., required royal approval for land grants in or adjacent to Indian territory.

(1710-1763)

Portrait by William Hoare, 1763

William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne, head of the Board of Trade in the Halifax-Grenville-Egremont ministry, was entrusted, as a result of the Treaty of Paris, to draft a policy for the newly acquired territory in North America. On 8 June 1763, Shelburne recommended the Appalachians incorporate the dividing line between the settlers and an Indian reservation to safeguard a projected colonial settlement in the upper Ohio, as well as terms for an Indian settlement east of that line. Out of the newly acquired territory three new provinces were created: (1) Quebec; (2) East Florida; and (3) West Florida. Boundaries were confined within modest limits that would not trespass upon the Thirteen Colonies.

“The sun of Great Britain will set whenever she acknowledges the independence of America – the independence of America would end in the ruin of England.” -gov.uk

News of an Indian crisis reached the British ministry in August before the plan was put into effect, and Shelburne was replaced (2 September) by the less-experienced Earl of Hillsborough who was a close associate of the 2nd Earl of Halifax. Halifax then prepared a new proclamation after reworking Shelburne’s proposal by omitting the provision for the upper Ohio settlement and ordering the colonists already settled in the area to “forthwith to remove themselves.”

(seated right) with his secretaries

Purchases of land from the Indians east of the line were then forbidden. Indian territory west of the line was put under the control of the military commander-in-chief in America, and English law was established in Quebec. The French settlers in Quebec considered the laws unfair and anti-Catholic. The proclamation was rushed through the Cabinet and Privy Council, which was then signed by the king (7 October).

***

Imperial officials were straightforward about their desire to see Quebec be the focus of population and territorial growth in 1774. Merged into the empire under the Proclamation of 1763, Quebec, not Williamsburg or Philadelphia, would be where land patents were issued for the Ohio Valley. The Proclamation had definitively repudiated the colonial charter claims of land “from sea to sea” (Jacobs, Wilbur R. British Indian Policies to 1783. Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 4: History of Indian-White Relations; p.10). After defining the new colonies, the Crown notified its subjects about the territorial readjustments. It annexed the Islands of St. John and Cape Breton, or Isle Royale with the lesser Islands adjacent thereto, placing them under Nova Scotia’s colonial government.

This decision was viewed as a punishment to the Massachusetts Bay Colony for its prudence during the Seven Years War. It didn’t seem to matter to the Crown that Massachusetts militiamen regularly fought for and seized the island in previous conflicts with France. Massachusetts officials’ also held a fixed interest in the fishing grounds to the north and it might have reasonably been assumed that this jurisdiction would have been granted to Massachusetts. On the other hand, another likely scenario could have been that Britain had to deal with the aftereffects of an earlier decision to exile the Acadians. By putting the islands under Nova Scotian governance, the Crown may have presumed it would limit Acadian unrest in Quebec should exiles seek to return home.

Then there were boundary disputes between Georgia and South Carolina that forced the Crown to annex to the Province of Georgia all lands lying between the Rivers Alatamaha and St. Mary. The truth of the matter continues to remain unsettled; was action taken against South Carolina because of the problems with the Cherokee conflict of 1761? What is known, however, is that Georgia, at that time, was smaller than South Carolina and its frontier less extensive than South Carolina’s. Therefore, the Crown may have preferably thought it could regulate the expansion of that frontier, which was the goal of the Proclamation of 1763.

The Proclamation was also set on creating governments for the two Floridas and Quebec. It was here that the Crown revealed its long-term policy objectives. The governors of Florida and Quebec were permitted to grant land so its populations could increase more quickly. This growth promised to happen on the lands where existing colonies hoped to settle their own people. Americans were confused why they were prevented from settling on lands their militias won.

Having encouraged Quebec and Florida to generate conditions that would attract new settlers, the Proclamation had to address an impending economic crisis – fifty thousand soldiers and several hundred officers were returning to England and to their retirement at half pay. The Proclamation promised servicemen who remained in America “Quantities of Land” that ranged in size from fifty acres for “every Private Man” to five thousand acres for a “Field Officer.” The Crown hoped the offer would keep many British veterans from returning to England, as well as to ensure a sufficient supply of soldiers in case they should be needed on the North American frontier.

Although the Proclamation did not stipulate where the soldiers had to take their land, there was an assumption that the lands taken would be in the territory given to Quebec. The reason came from a paragraph that followed the grants claiming it was “essential to our [England’s] Interest” that lands of “the Several Nations or Tribes of Indians with whom We are connected…are reserved to them.” And in case the colonists and their governments missed this point, the paragraph concludes: “no Governor or Commander in Chief” could grant any “Warrants of Survey” or pass “any Patents for Lands beyond the Bounds of their [current] respective Governments” until further notice was given. Furthermore, those people who “either willfully or inadvertently seated themselves upon any Lands…reserved to the said Indians” were to “remove themselves” at once. The colonists were also forbidden from “purchasing Lands of the Indians.” Many colonists thought the justification for fighting the French and Indian War had simply disappeared.

The Crown, not colonial autonomy would make all future land purchases. The customary freedom of the colonies in Indian land purchases had ended. Imperial officials would determine future colonial growth, and that did not mean purchases came to a complete end – Georgia officials secured more than 5,500,000 acres of land in three sessions between 1763 and 1775. However, the prohibition of land purchases was the Proclamation section that received most of the attention from colonists and speculators.

The Board of Trade members, in their minds, brought the unregulated western settlement to an end and used the Proclamation to restructure commerce with the Indians. The Proclamation promised a better method for settlement systems as well as a more competitive and profitable environment. This opened the Indian trade to “all our subjects whatever,” which stipulated that only traders receive licenses from a colonial governor – this provision opened unexpected trouble. Colonial governors then licensed almost any trader who applied for one and soon traders swarmed the Indian country in pursuit of skins and profits. The Proclamation had no mechanism to regulate such activities. Trade took place not only beyond the fort walls but also on the boundaries of Indian communities. Privy council members seemed to recognize the problems the Proclamation unintentionally caused, since they discussed the matter later with Indian Superintendent Sir William Johnson, and they expressed the need to create regulations for the trade problem. Before the regulations could be established, however, traders sought out new locales, including the new West Florida (Calloway, Colin G. The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America; pp. 109-110).

The idea of separating Indians from colonists appealed to many southern Indian groups. Cherokee elders long considered using dividing lines when it came to conflict resolution. This approach resolved a Cherokee-Creek conflict and it was used again in 1762 to negotiate a Cherokee war decision. The change in colonial impressions regarding the backcountry during the 1760s meant negotiating boundary limitations, and that is what occurred in the 1765-67 period. The Proclamation also reserved land to the Crown that was not specifically given to East and West Florida or Quebec.

What the Proclamation did not do was suspend the colonial charters or deny all existing colonial land claims. It also did not propose to send additional troops to the colonies – though it was suggested by Maurice Morgann to William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne, the president of the Board of Trade. Officials, such as Egremont, Shelburne, and John Pownall, were more interested in the calculations on how to combine the needs of imperial policy with the wishes for colonists in the western lands.

***

The acquisition of Canada and other territories in 1763 more than doubled the dominion for the British Empire; however, it created complex problems governing. The Seven Years War (French and Indian War) left the British government with a staggering burden of debt.

English landlords and merchants objected furiously to expanding taxes, while the halfhearted war effort by the colonists showed a ‘healthy neglect’ for participation. And since Great Britain retained the undisputed title to the West as well as to Canada, the new peace brought additional problems for administration and defense. British statesmen feared France would launch another attack somewhere in America, especially since they were not completely crushed at the end of the war, with a plan to recover her lost territories and status.

Responsibility for the solution of the postwar debt fell upon the new, young monarch George III, who came to the throne in 1760. Then by 1763, the British prime minister, George Grenville, was assigned direct responsibility for the debt solution. As brother-in-law to William Pitt, Grenville did not share in Pitt’s sympathy with the colonial viewpoint. He approved of the prevailing British opinion that the colonists should be forced to obey the laws and pay its portion of the cost to defend and administer the empire. He was also Chancellor of the Exchequer and First Lord of the Treasury and quite familiar with matters of public finance. Thus, he hastily engaged himself in the network of an unorganized collection of American colonial possessions.

George Grenville (1712-1770)

William Pitt – the Elder (1708-1778)

Nevertheless, conditional motions to impose a royal presence in North America already existed prior to the years preceding the war, but those acts were not enough. The war clearly showed how independent the American colonies had become. British officials were advised to rethink and restructure their relationship with the American colonies, but British officials saw the postwar period as an opportunity to firmly reclaim their parliamentary control over the colonies.

One particular area in which imperial officials were very proactive in affirming their royal authority was in the Indian affairs. Nothing worried policy makers more that the colonial effort to take Indian land, especially if done illegally. From London’s viewpoint, it was the colonial claims to western lands as well as the colonist’s insistence to settle those lands that caused the Seven Years War. Thus, when the colonial conflict became an international warfare, imperial officials found they were unable to focus exclusively on their North American colonists.

The colonies, however, speculated solely on the defeat of Canada, while the attention of London officials were diverted to their affairs in the Caribbean, Europe, Africa, and Asia. The effects from London’s preoccupation was a persistent struggle between the royal and colonial officials over the war in North America. The colonial governments were not shy about airing their grievances about their burden to pay for the war, especially since they had no say in how it was negotiated. William Pitt’s promise in 1758 to reimburse colonial governments for the expenses of war resolved some of the problems, but at a steep price. Britain had an enormous debt crisis. The colonists’ challenge to London on both money and military matters exposed how much power colonial legislatures assumed over the years.

proclamation line of 1763

At this point, the American western problem was the most urgent because the frontiersmen from the English colonies quickly proceeded over the mountains into the upper Ohio River Valley as soon as the French departed from America. Then a federation of Indian tribes, led by chieftain Pontiac, promptly objected to the trespass and Pontiac raised the war cry. Great Britain issued an emergency measure – a proclamation forbidding settlers to advance beyond a line drawn along the mountain divide between the Atlantic and the interior. The emergency Proclamation was passed and the principle of the Proclamation Line of 1763 remained – the principle of controlling westward movement of population.

Initially, Great Britain encouraged rapid expansion of population into the frontier for reasons of both defense and trade. Then, over time, the official attitude changed because of a fear that the interior territory might draw away too many people that would weaken markets and investments near the coast. There was also the desire to reserve land speculation and fur trade opportunities specifically for the English rather than for enterprising colonists. After the new policy in 1763, the British government soon expanded it.

A definitive Indian boundary was set and it was expected that such a boundary could be relocated with an agreement from the various tribes. Eventually, western land would be gradually reopened for further occupation and settlements; however, such a movement west would be carefully supervised to ensure the operation proceeded in a lawful and organized manner.

Next, in order to provide a defense for the colonies, raise revenue, and enforce imperial law within the colonies, the Grenville ministry cooperated with Parliament by establishing a series of measures that were for some familiar in principle and, for others, entirely novel.

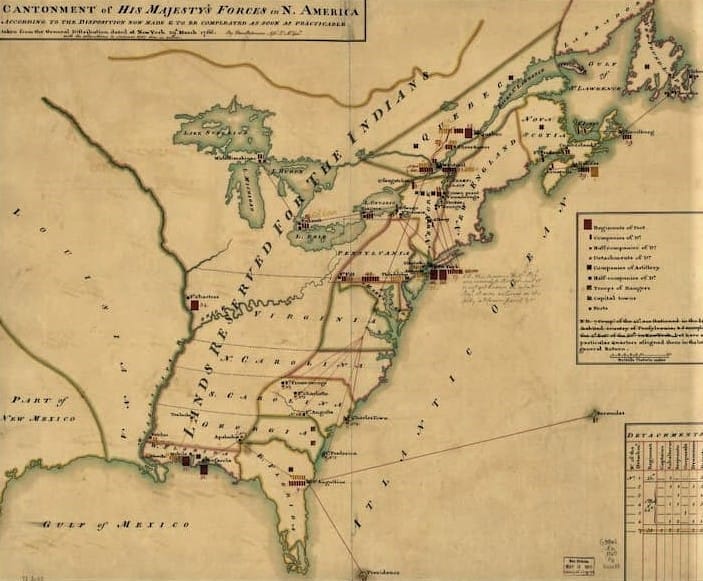

Regular troops were then permanently stationed in the provinces, and the colonists by 1765 would be called to assist in provisioning and maintaining the army. The colonists were also subjected to the longstanding British regulations for military crimes, which carried penalties for desertion and refusal to obey superior officers, among other major military crimes (The Papers of Benjamin Franklin. The Mutiny Act, 1756; vol.6, 1 April 1755 through 30 September 1756; pp. 433-437).

***

With the establishment of the Proclamation Line, the British not only upset the traders but the new settlers in the west as well. These settlers had, after all, come to the New World on the promise of open land but unexpectedly discovered the land was occupied by primitive and barbarous people (Every, D.V. Forth to the Wilderness: The First American Frontier, 1754-1774 [1961]). Some settlers simply broke the law and moved beyond the line. Still, others used the political process and tried to influence the government, without much success.

Both the Paxton Boys movement of 1763 in Pennsylvania and the 1771 Regulator movement in North Carolina alarmed settlers in the western regions that they were ultimately responsible for defending themselves, regardless of the high taxes they were obligated to pay to the colonial government in order to support their defense. The westerners complained their taxes were not only unfair, but oppressive burdens when unjustly imposed.

Hopes for expansion to move westward only aggravated such matters. By 1774, Lord Dunmore of Virginia defeated the Indians in the Kanawha River Valley, opening the trails of Kentucky to settlement. This white-Indian encounter has been traditionally described as the Europeans stealing land from the Native Americans, however, it was in reality a much more complex exchange. Many Indian tribes rejected the European opinion of property rights in which land could be privatized. These Indians believed they were incapable of owning land because such an idea created strong motivations for tribal leaders to trade their land for high-end merchandise. Under their normal way of life without property ownership, such a trade would be difficult to obtain. Realistically, chiefs were no different than the Europeans in the respect that they too could be corrupted, and these Indians understood this. In the aftermath of the treaty, the Indians were very surprised to learn that land could actually be closed off to certain people (White, R. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815 [1991]). With such different world views, conflict was inevitable. If not for the reasonableness provided by Christianity and British concepts of humanity toward uncivilized enemies, such conflicts could have ultimately been far worse and bloodier.

Other Indian tribes, such as the Cherokee, realized they would not be able to control the flow of English settlers moving westward. In the fall of 1774, Captain Nathaniel Hart met with the Overhill Cherokees at their Otari towns to negotiate for the lease or purchase of a large tract of land between the Kentucky and Cumberland Rivers. Early in 1775, the Transylvania Company entered the negotiation to further clarify the terms of the joint venture. The Transylvania partners took what was alleged to be a flawless deed of millions of acres from the Cherokee chiefs. In March 1775, Daniel Boone, working for the Transylvania Company, was sent on an expedition with approximately 30 woodsmen to forge a trail from the Holston River in East Tennessee and across the mountains at Cumberland Gap to make the region accessible for new settlements. As a result, the Cumberland Gap trail quickly became the highway to the frontier (Sosin, J.M. The Revolutionary Frontier, 1763-1783 [1967]).

NOTE: Not long after the transaction, the Transylvania Company’s Cherokee land purchase was publicly condemned by the governors of Virginia and North Carolina. Its land scheme was annulled. As compensation to the Transylvania associates, the Virginia legislature created Kentucky County in December 1776 and, in 1778, granted Transylvania associates 200,000 acres on the Green River.

References

Bellot, L.J. CANADA VERSUS GUADELOUPE IN BRITAIN’S OLD COLONIAL EMPIRE: A STUDY OF GEORGE LOUIS BEER’S INTERPRETATION OF THE PEACE OF PARIS OF 1763. Rice Institute (1960)

Brigham, C.S., ed. BRITISH ROYAL PROCLAMATIONS RELATING TO AMERICA, Vol. 12 Transactions and Collections of the American Antiquarian Society

Gelder Lehrman Collection. King George III, PROCLAMATION OF 1763, (1763)

Greene, Taylor. SIR WILLIAM JOHNSON AND BRITISH NORTH AMERICAN NETWORKS OF POWER, 1738-1774. (2018)

Henderson, Archibald. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE TRANSYLVANIA COMPANY IN AMERICAN HISTORY (1935)

King George III – A PROCLAMATION. Complete document

Laub, C. Herbert. BRITISH REGULATION OF CROWN LANDS IN THE WEST: THE LAST PHASE, 1773-1775. William and Mary Quarterly 2nd series, 10, No.1 (Jan. 1930): Pp. 52-55

Lucas, C.P. HISTORY OF CANADA 1763-1812. (1909)

McCutchen, J.M. PROCLAMATION LINE OF 1763

Ohio History Central. PROCLAMATION OF 1763

Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 6, April 1, 1755 through September 30, 1756; pp. 433-437

Pickering, Dan. THE QUEBEC ACT: 7 October 1774. Avalon Project at Yale School – Great Britain – Cambridge: Benthem, for C. Bathhurst; London, 1762-1869

Pownall, John. PROCLAMATION OF 1763. Board of Trade, Great Britain – American Colonies in Resistance and Revolution

Ridpath LLD, J.C. THE COMPLETE HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. Vol. 5, p. 2277

Sosin, Jack M. WHITEHALL AND THE WILDERNESS: THE MIDDLE WEST IN BRITISH COLONIAL POLICY, 1760-1775. Lincoln, NE: Univ. of Nebraska Press (1961)

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION: TREATY OF PARIS

TREATY OF PARIS, 1763. George III, King of Great Britain (10 Feb.1763). Avalon Project at Yale School