- Post Contents -

progression of american music

The progression of American music began with America’s early settlers – the religious Separatists called Pilgrims. They established a colony in Plymouth, Massachusetts, and as to their musical life in the Plymouth colony, there is little information known about any musically gifted settlers. No record was found that kept the actual practice of singing in the colony’s first critical years; however, it is known that song in worship was one of their cherished and characteristic customs. This is known because of the music they brought with them, as well as the implication from the passage in Edward Winslow’s Hypocrisie Unmasked (1646) in which he described how in 1620 the large Leyden congregation in Holland bid farewell to those Pilgrims setting out for America:

They that stayed at Leyden feasted [with] us that were to go at our pastor’s house, [it] being large; where we refreshed ourselves, after tears, with singing of Psalms, making joyful melody in our hearts as well as with the voice, there being many of our congregation very expert in music; and indeed it was the sweetest melody that ever mine ears heard.

Edward Winslow – Hypocrisie Unmasked – 1646

EARLY AMERICAN MUSIC

1600s – 1700s

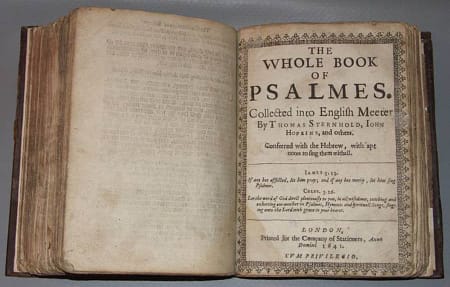

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, English Protestants based their congregational singing on the metrical versions of the Psalms. All early service books of this type were called ‘Psalm-Books’ and were not replaced by ‘Hymn-Books’ until the 18th century. The first complete metrical Psalter in English was first published in 1562 – commonly known as ‘Sternhold and Hopkins’.

In 1564, a Scottish variant appeared and it was based mainly on the same material but with substantial differences. The two books dominated the British field for more than a century and as new colonies in the New World were settled, they all brought over the English Sternhold and Hopkins, but not Plymouth colony.

The Psalter brought to Plymouth was prepared especially for the fugitive Pilgrims from the Separatist congregations in Holland by Henry Ainsworth. It was published in Amsterdam in 1612. This Psalter was also adopted at Salem and used for about a generation. At Plymouth, it was used much longer even after the Pilgrim settlement merged with Massachusetts Bay in 1692. By that time, it was replaced by The Bay Psalm-Book, which was a new American book published at Cambridge in 1640. A revised version of The Bay Psalm-Book appeared around 1650 and was often reprinted. This ‘New England Version’ remained the characteristic American Psalter for a long time. However, Ainsworth’s Psalter was in use at Plymouth many years prior and it carried more importance that the Bay Psalm-Book ever would.

According to F.S. Allis, Jr. from the publication Music in Colonial Massachusetts, 1630-1820:

Puritans settled the Massachusetts Bay Colony and dominated the area for several generations. It is well known that they simplified both the poetry and meter of the psalms, that they gradually changed from reading music to singing by rote, and that they prohibited the use of musical instruments during religious services. These and other facts led most nineteenth-century music historians and some from the present century to believe that the Puritans forbade secular social music and permitted only the recreational singing of psalms.

In the light of new evidence, however, a group of twentieth-century scholars began to question this commonly held belief. Heading the movement which was to demonstrate that secular social music was in fact practiced in the Bay Colony were Percy Scholes and Henry Wilder Foote. In ‘The Puritans and Music in England and New England’, Scholes established that there was a musical culture outside psalmody and that the Puritans participated in it. His argument was based largely on the musical practices of the English Puritans with some supporting evidence from New England. And Henry Wilder Foote in ‘Musical Life in Boston in the Eighteenth Century’ asserted that Boston had an early thriving musical life, and used as evidence findings by Sonneck and Scholes as well as his own research into the sacred singing controversy.

In his quest for evidence that the New England Puritans practiced secular music, Scholes found few references to musical instruments. He culled a ‘treble viall, 10s’ from the will of Nathaniel Rogers of Ipswich (d. 1655) and a reference to fiddling as well as dancing from a Salem Court case of 1679.

From the diary of Samuel Sewall, the noted New England judge and journalist (1652–1730) who left so vivid a picture of life in the Massachusetts Bay Colony between 1674 and 1729, Scholes found reference to a virginal, a dulcimer, a fiddle, and several trumpets. Scholes continued to believe strongly, however, that the colonists, including the Puritans, practiced secular social music.

In short, when this study was begun, it was known that the New England Puritans had emigrated from a country rich in secular music; that their religious brethren in England continued to practice and sponsor secular social music, and that at least a few of the New Englanders had owned musical instruments. However, still lacking was definitive evidence of the existence of secular social music in New England prior to 1729.

F.S. Allis, Jr. in the publication Music in Colonial Massachusetts, 1630-1820: Music in Homes and Churches, volume 54

1600s

The 1600s was a time in music history when a modern viewpoint of structure and effect replaced the old musical arrangements of the medieval period. It was also a time when dramatic, rhythmic operatic dialogue (recitative) and an airy, opera solo vocal piece (arioso) were recognized, as well as when Ainsworth evolved his Psalter into the musical drama we know today as the ‘opera’ (e.g., Monteverdi’s Orfeo produced in 1603 and his Arianna in 1608).

The main factor in the movement that took place in all artistic music was the impulsive experiments that were discovered in popular songs of several countries. Those popular songs influenced the new Protestants to accept and adapt them for religious use. This too was true for Germany, Switzerland, France, the Rhine Valley, the Low Countries, and across the English Channel.

The first stage of this change developed into the latter half of the 17th century, then continued into a second stage, especially in Germany, when the original materials were worked into a more sophisticated type of traditional ‘chorale’. This stage became the basis for new instrumental developments, which continued into the first half of the 18th century and the great works of Bach.

Early traditional cultures of the North American, Indigenous Indian also used music as an important part of their everyday life as well. Their songs and chants accompanied religious rites and festivals, but the concept of performance music as an art was non-existent for them as it was for the 17th-century settler in New England. The music of both cultures was specifically intended for religious observances in community services and ceremonies.

MUSIC TIMELINE

1700s

1720. Boston and its neighboring towns disputed psalm singing in public worship. The reformers complained bitterly that the congregations sang badly. They proposed singing ‘by rule’ or ‘regular singing’ be improved as well as the standardization of the practice of psalmody. Singing schools were formed to teach the new way, but most people resisted the reform and conflicts arose in some congregations over singing.

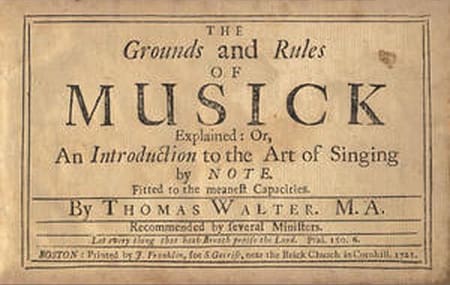

1721. Rev. Thomas Walter (1696-1725) from Roxbury, Massachusetts, printed the first music with barred notes titled The Grounds and Rules of Musick Explained, or An Introduction to the Art of Singing By Note.

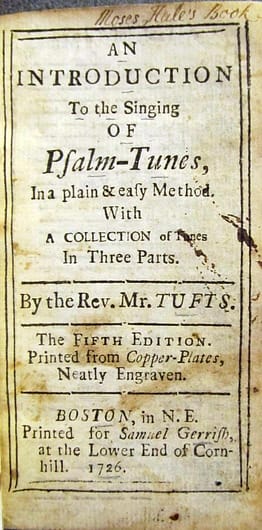

1726. Rev. John Tufts (1689-1750) from Dedham, Massachusetts, arranged the 100 Psalm Tune New and it was believed to be the first American composed music published in his fifth edition tune collection called An Introduction to the Singing of Psalm-Tunes.

1729. The first known public concert in the colonies was held in Boston. It was advertised in the Boston Gazette, 2 February 1729, as ‘a Consort of Musick performed on sundry Instruments at the Dancing School in King Street’. It was most likely carried out by musicians from England, and the program presumably consisted of European pieces.

1730. Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) printed in Philadelphia the first collection of German Hymns called Gottliche Liebes Und Lobes Gethoene.

1735. The earliest known opera performed in America was held in Charleston, South Carolina. The work was Flora, an English ballad opera.

1751. Francis Hopkinson (1731-1791) wrote Ode to Music – the first piece of instrumental music by a native-born American. He was America’s first notable composer and a man of amazing versatility. He was the first student graduated from the College of Philadelphia, he went on to practice law, served in the first Continental Congress, and signed the Declaration of Independence. He wrote verse, essays, and Revolutionary pamphlets. He painted and played on the harpsichord for public performances. He composed music, sat as a judge in Pennsylvania as well as in federal courts.

1759. Francis Hopkinson (1731-1791) wrote the music for My Days Have Been So Wondrous Free and the text was by Irish poet and clergyman Thomas Parnell (1679‑1718). This song was considered the first American art song and the earliest surviving secular composition. It was scored for voice and harpsichord.

1761. The earliest occurrence of identified new compositions published by an American composer was James Lyon’s (1735-1794) Urania (1761); a collection of sacred music that contained six tunes that were marked as new and published in Philadelphia. It was the first tune book to identify contributions of American composers.

Young Johnny, sung by Winifred Bundy – An early American ballad that concerned the death of Thomas Mirrick from a snakebite while mowing a field in Wilbraham, Massachusetts colony, 1761. Twenty-year-old Mirrick died from the snakebite shortly before he was to be married, which inspired the making of the ballad, The Elegy of the Young Man Bitten by a Rattlesnake. The song varies in oral tradition as Springfield Mountain or Young Johnny. See below.

According to Derek Strahan, 2015, from lostnewengland.com and Merrick’s sixth great‑grandson about the Merrick story:

Massachusetts is home to only two species of venomous snakes: the timber rattlesnake and the northern copperhead. Both are exceedingly rare in the state, but they must have been more common in Wilbraham in the past, as they make several appearances into town lore. This house was built around 1761 for Timothy Merrick, the only son of my 6th great grandfather, Thomas Merrick. Merrick was engaged to Sarah Lamb, and they were to live in this house after their marriage. However, according to the records of the town clerk, Samuel Warner (who was also my 6th great grandfather, from a different branch of the family):

“Timothy, son of Thomas Mirick and Mary Mirick, was Bit By a Ratel Snake one Aug. the 7th, 1761, and Dyed within about two or three hours he being twenty two years two months and three Days old and vary near the point of marridge.”

Merrick’s death is believed to be the last recorded fatal snake bite in Massachusetts history, but even if not it is certainly the most famous. Because of the tragic nature of the story, this event formed the basis for one of the earliest American ballads, “On Springfield Mountain.” It was written in the late 1700s or early 1800s, and there are many different versions of this song, some of which include a number of embellishments beyond what Warner wrote in the town records.

Derek Strahan, 2015 – lostnewengland.com

1762. The Military Glory of Great Britain was an entertainment for the commencement anniversary ceremony at Nassau Hall in Princeton, New Jersey. The music was likely written by James Lyon (1735-1794).

The St. Cecilia Society was the first musical society founded in Charleston, South Carolina.

1765. Moravian Church composer, Jeremiah Dencke (1725-1795), was the first American to write vocal music accompanied by an instrumental ensemble. He wrote his first American composition for the ‘Liebesmahl’ (Love Feast) held in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania 29 August 1765.

1766. Josiah Flagg (1737-1794) Composed and published Sixteen Anthems – to which were added a Few Psalm Tunes, which was one of the first collections of American sacred music written for singing instead of congregational use.

1767. Francis Hopkinson (1731-1791) – wrote Psalms of David for the Dutch Reformed Church.

1768. John Dickinson (1732-1808) wrote the poem, Liberty Song (1768), to be sung to the anthem music of the British Royal Navy Hearts of Oak (1759). First published in the Boston Gazette in 1768, and later published the same year in the Boston Chronicle. It was sung throughout the colonies at political meetings, dinners, and celebrations. The most famous passage in the song is the source of a phrase known to many Americans centuries after: By uniting we stand, by dividing we fall.

1769. Daniel Bayley (1729-1792) combined William Tans’ur’s Royal Melody Compleat (London, 1754) with Aaron William’s Universal Psalmodist (London, 1763) as The American Harmony – four editions were published between 1769 and 1774.

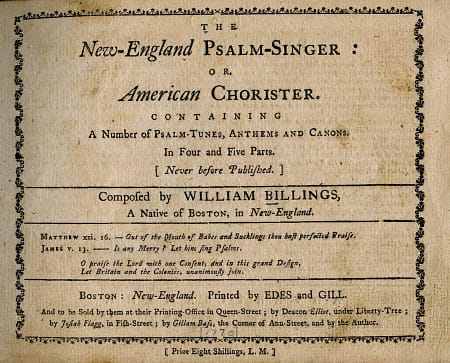

1770. William Billings (1746-1800) published in Boston The New-England Psalm-Singer or American Chorister – a collection of 126 hymns and choral pieces that he composed himself, which included an engraved frontispiece by Paul Revere. Billings became the first American composer to issue an entire collection of his own music and, even for a European, such a collection would have been an exceptional feat. Before this collection, there were very few published choral pieces written by Americans.

1773. The broadside song Tea, Destroyed by Indians was published after the Boston Tea Party.

1774. Joseph Warren (1741-1775) wrote the tune Free America from the tune The British Grenadier, warning Americans not to bow to tyrants and end up like ancient Greece and Rome.

1775. A ballad about the British attack on Bristol, Rhode Island on 7 October 1775 was called The Bombardment of Bristol.

Andrew Law (1749-1821) wrote the tune Bunker Hill, which was set to Nathaniel Niles’s (1741-1828) poem, commemorating the Battle of Bunker Hill of 17 June 1775.

J.W. Hewlings (d. 1793), was a native of Nansemond, Virginia. He wrote the ballad American ‘Hearts of Oak’.

1777. Minorcan folksong, Fromajadas, was sung on Easter Eve by bands of singers while asking for cheesecake. Minorcans, from the island of Minorca, off the coast of Spain, first came to Florida in 1768, along with Italians and Greeks, and led by Dr. Andrew Turnbull (1718-1792). Turnbull settled New Smyrna Beach, Florida. The colony ended in 1777 because of poor working conditions for the laborers and harsh treatment from overseers.

1778. William Billings (1746-1800) composed, wrote the lyrics and published The Singing Master’s Assistant. A revised version of his patriotic song Chester was also included. Chester was a popular tune during the American Revolution, however, his revised version of the song was more popular.

An Alaskan Yup’ik song – The tune is from a vision of the arrival of Europeans in Alaska by a Yup’ik medicine man in 1777, a year before the exploration and mapping of the Alaska coastline by Captain James Cook (1728-1779) between April and September 1778. They lived remotely north of the areas favored by Russian fur traders, and further contact with Europeans was unlikely until later in the 19th century.

1780s

The music trade business was established. It consisted of a group of music publishers (not book publishers who issued collections of music), music sellers, instrument makers, and dealers in musical supplies. The trade was centered in cities on the East Coast; Philadelphia, Boston, New York, and Baltimore.

Also at this time, a grassroots tradition of instrumental music grew from the military.

1780. Francis Hopkinson (1731-1791) wrote an Ode in Memory of James Bremner.

1781. William Billings (1746-1800) published The Psalm Singer’s Amusement. It contained fuging tunes and anthems. The fuging tune originated in Britain in Anglican parish churches as a way of elaborating metrical psalmody, taking hold among country choirs in the period 1745–65.

Francis Hopkinson (1731-1791) wrote The Temple of Minerva, an operatic libretto, and it was first published as a broadside to be sung to music adapted from pre-existing music. It’s not known if The Temple of Minerva was a “dramatic cantata,’ performed with scenery but not acted, or if the work was staged as a miniature grand opera. He has been considered either the first American cantata composer or the first American opera composer.

1783. Andrew Law (1749-1821) published The Rudiments of Music: or a short and easy treatise on the rules of psalmody.

1784. Abraham Wood (1752-1804) wrote A Hymn for Peace, which was published in 1784 by William Billings. He was an American composer and tune book compiler who wrote several songs about the Revolutionary War.

1786. Alexander Reinagle (1756-1809) emigrated to New York from England, then moved to Philadelphia. He played an important role in the development of music in American life. He was most famous for his four piano sonatas of 1790, considered the “finest surviving American instrumental productions of the 18th century.” He was noted as an accomplished music teacher in Philadelphia and gave piano lessons to George Washington’s adopted daughter, Nelly Curtis.

1787. The ballad The Grand Constitution was an arrangement to the English tune Heart of Oak, honoring the U.S. Constitution.

1788. Francis Hopkinson’s (1731-1791) best-published collection of work was Seven Songs for the Harpsichord or Forte Piano and it was dedicated to the composer’s friend George Washington. Included was the song The Toast written in honor of Washington.

1789. Abraham Wood (1752-1804) wrote a book Divine Hymns of 1789 sets texts by English hymnodist and preacher Joseph Hart (1712-1768). Wood also wrote A Funeral Elegy on the death of General George Washington (1799).

One of the songs that honored George Washington’s Inauguration was Ode to the President of the United States and it was arranged to the tune God Save the King.

1790s

A movement to reform sacred music sprung from certain musicians who denounced the apparent crude style of music composed by Americans. They proposed a turn to European harmonic and melodic practice. Their movement was accepted by some and ignored by others.

Alexander R. Reinagle (1756-1809) and his business partner Thomas Wignell (1753‑1803), an English actor, were important players in the theater scene. They started ‘The New Company’ that toured between Philadelphia and Baltimore. The company performed ballet and light opera to spoken and musical plays. Reinagle composed many pieces from incidental songs to complete productions. Due to a Philadelphia theater fire in 1820, most of these arrangements were lost.

1790. Samuel Holyoke (1762-1820) wrote the song Washington as a memorial for the presidential inauguration to George Washington.

1791. Hans Gram (1754-1804) composed the music for The Death Song of an Indian Chief, its text was written by poet Sarah Wentworth Morton (1759-1846) the Ouabi; or The Virtues of Nature. An Indian Tale. In Four Cantos – was published in 1790. This song is considered the first orchestral score published in America.

1792. James Hewitt (1770-1827) an English-born conductor, composer, and publisher emigrated to New York. He was influential in the city’s musical life becoming the conductor of the Park Street Theatre. His compositions included the song, In Vain the Tears of Anguish Flow.

Oliver Holden (1765-1844) wrote the tune Coronation to Edward Perronet’s (1721‑1792) hymn All Hail the Power of Jesus’ Name. One of the earliest American hymn tunes still found in most Protestant hymnals.

Raynor Taylor (1747-1825), an English-born composer who emigrated to Philadelphia, became an active member of the musical life in Philadelphia. He was best known for his piano music, composing many settings of comic texts, including The Loves of Jockey and Jenny and The Scotch Wedding (1793). He was also one of the founders of the Musical Fund Society.

1793. Victor Pelissier (1740?-1820) was a French composer, arranger, and horn virtuoso. In 1792, He was first mentioned in the United States on a concert advertisement as a horn player in Philadelphia. In 1793, he went to New York to play in the orchestra of the Old American Company and became one of its principal composers and arrangers. Back in Philadelphia in 1811, he began publishing Pelissier’s Columbian Melodies, which consisted of multiple volumes of theater songs, dances, and instrumental music arranged for piano. He is one of the first American composers to write an independent keyboard accompaniment in his songs. He is credited with the first American opera, Edwin and Angelina.

1794. Benjamin Carr (1768-1831) Born in England, Benjamin Carr emigrated to Philadelphia in 1793 and opened a notable music shop. He found success as a publisher, a notable tenor, organist, and composer. He published 71 songs throughout his lifetime and played an important role in the development of early American musical life.

Alexander Reinagle (1756-1809) Born in England, Reinagle also emigrated to New York in 1786 and played a vital role in the development of American musical life. On his arrival in New York, he taught and performed music. He then moved to Philadelphia where he revived the City Concerts for 1786-87 with a series of 12 concerts. The City Concerts featured European works alongside Reinagle’s own compositions. An accomplished teacher in Philadelphia, Reinagle gave piano lessons to George Washington’s adopted daughter Nelly Curtis (see 1786).

Alexander Reinagle was most famous for his four piano sonatas of 1790, considered by many scholars to be the “finest surviving American instrumental productions of the 18th century. When he died in 1809, he left his oratorio Paradise Lost unfinished.

Several important tune collections published were: The Continental Harmony by William Billings and The Harmony of Maine by Supply Belcher of Farmington, Maine. Belcher was originally from Stoughton, Massachusetts.

1797. James Hewitt (1770-1827) was born in England and emigrated to New York in 1792. He was a composer of over 84 songs and a significant participant in the early New York musical scene. In 1808, he conducted the orchestra of the Park Street Theatre and arranged and composed music for the theatre. Throughout his life, he published over 639 compositions, including those of British composers and at least 160 of his own. His compositions were largely based on American patriotic tunes and ballads – e.g., The Battle of Trenton was dedicated to George Washington, Washington’s March, and Yankee Doodle.

1798. Joseph Hopkinson (1770-1842), was Francis Hopkinson’s son and a distinguished lawyer himself. In 1798, Mr. Hopkinson’s friend pleaded for him to write some patriotic verses to the tune of the ‘President’s March’, as he was to sing a benefit the following evening and not a single box had been taken. Mr. Hopkinson’s friend was fearful of a lackluster attendance and he needed Hopkinson’s help. Mr. Hopkinson obliged and quickly wrote the first verse and chorus and his wife sang them to a piano accompaniment. The measure and music were approved and it was agreeable for keeping. The revised tune, Hail Columbia, was cheered night after night by the patrons of the theater, and it became the universal song for all the street boys throughout the city.

Popular songs during and after the Revolutionary War were mostly patriotic. Supporters of the American cause rewrote familiar English tunes with words that ridiculed their adversaries, and one such song was Yankee Doodle.

Yankee Doodle was written during the French and Indian War by a British army surgeon, whose intention was to make fun of the ragged colonial troops but the tune became a favorite with the American Yankee. During the Revolutionary War, those Yankees added many variations of the song with some variations unsuitable for polite company.

After the Revolutionary War, the cultural mood was optimistic and the new Americans wanted their own culture free from British influence. However, concert music continued to be dominated by European influence after the War. There was Johann Christian Gottlieb Graupner (1767-1836) who co-founded Boston’s Philharmonic Society (ca. 1810‑1825) and the Handel and Haydn Society (est. 1815). New York’s James Hewitt (1770-1827) composed the favorite military sonata, The Battle of Trenton, which was dedicated to General George Washington.

There were American composers who believed the national music could be created from nature’s inspiration, local material, and pure Yankee imagination. Such composers were William Billings (1746-1800), Anthony Philip Heinrich (1781-1861), and Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-1869). There were other composers who wanted American music regulated by the standards and rules of the great European masters like Haydn and Mozart; men such as the critic – John Sullivan Dwight (1813-1893), the founder of American school music education and co-founder of the Boston Academy of Music – Lowell Mason (1792-1872), and the recipient of the National Conservatory prize in music composition – Horatio Parker (1863-1919).

– Commentary –

The development of American music progressed slowly because of conflicts between personal and professional preferences from former cultures and traditions; however, America’s freedom of expression will always be preferable over regulation and control as long as the United States remains free.

– References –

Ainsworth, H. 1571-1622, W.S. Pratt, 1857-1939. Book of Psalmes. Publisher: New York, Russell & Russell – publication date 1971. The music of the Pilgrims; a description of the Psalm-book brought to Plymouth in 1620.

https://archive.org/stream/musicpilgrimsad00ainsgoog/musicpilgrimsad00ainsgoog_djvu.txt

https://archive.org/details/musicpilgrimsad02ainsgoog

https://archive.org/stream/musicpilgrimsad00ainsgoog#page/n11/mode/1up

American Revolution.org. 2017. 1775 American ‘Hearts of Oak’. The JDN Group, LLC.

http://www.americanrevolution.org/war_songs/warsongs25.php

“The American hero. Made on the Battle of Bunker-Hill, and the burning of Charlestown,” Isaiah Thomas Broadside Ballads Project, accessed July 2018. Nath. Niles 1775. http://www.americanantiquarian.org/thomasballads/items/show/176

Brooks, L., Berea College, C. Young. 2003. The Gale Group. Essay adaptations.

https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/history-african-american-music

Allis, Jr., F.S., et.al. Colonial Society of Massachusetts. Music in Colonial Massachusetts, Vol. 54.

https://www.colonialsociety.org/node/2030

Cox, R.S. 1998. Re-cataloged by S.J. Schopieray, 2008. Andrew Law Papers. William L. Clements Library, Manuscript Division, University of Michigan.

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/clementsmss/umich-wcl-M-1131law?view=text

Crawford, R. 1979. This paper is a revised version of a talk presented on April 18, 1979, at the Semiannual Meeting of the Society, held at The Newberry Library, Chicago.

http://www.americanantiquarian.org/proceedings/44539323.pdf

Crawford, R. 2001. Fuging Tune. Grove Music Online. Oxford Index.

http://oxfordindex.oup.com/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.10358

Current, R.N., T.H. Williams, F. Freidel. 1961. American History: A Survey. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Dickinson College Archives. 2005. The Liberty Song, (1768). Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections.

http://archives.dickinson.edu/sundries/liberty-song-1768

Gann, K. 2018. What is American About American Music? American Public Media. In association with the San Francisco Symphony; M.T. Thomas, Music Director.

http://musicmavericks.publicradio.org/features/essay_gann02.html

Graziano, J. 2018. A-R Editions. Recent researches in American music.

https://www.areditions.com/recent-researches/american-music

Hall, R.L. 2006-2018. American Music Preservation.

http://www.americanmusicpreservation.com/Americanmusictimeline.htm

Hildebrand, D.K. 2001. Updated 2015. The Colonial Music Institute.

https://www.colonialmusic.org/colonial-music-resources/2-uncategorised/31-about-early-american-music.html

Joseph Hart-1789. Music.com.

http://hymnbook.igracemusic.com/

Josh. 2014. Dr. Andrew Turnbull and the Origins of New Smyrna Beach. Florida Memory State Library & Archives of Florida.

https://www.floridamemory.com/blog/2014/05/14/dr-andrew-turnbull-and-the-origins-of-new-smyrna-beach/

Leiden American Pilgrim Museum, the Netherlands.

http://www.around-amsterdam.com/pilgrim-fathers-in-leiden.html#gallery[pageGallery]/1/

Library of Congress. Biographies-Francis Hopkinson.

https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200035713/

Library of Congress. Digital Collections. Celebrates the Songs of America.

https://www.loc.gov/collections/songs-of-america/articles-and-essays/timeline/1759-to-1799/

Library of Congress. Book/Printed material: Tea Destroyed by Indians [1773].

https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.0370240a/

Library of Congress. 1777. Fromajadas. St. Augustine, Florida.

https://www.loc.gov/item/flwpa000294/

Library of Congress. 2003. Yup’ik song about a vision of a sailing ship in 1777.

https://loc.gov/item/ihas.200196499

McLucas, A.D. 2001. Oxford Index, Grove Music Online. Victor Pelissier.

http://oxfordindex.oup.com/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.21217

Music in Early America. http://musicinearlyamerica.weebly.com/18th-century.html

Randel, D.M.(Editor). 1996. The Harvard Biographical Dictionary of Music. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, and London, UK.

https://books.google.com/books?

Song of America. Hampsong Foundation.

https://www.songofamerica.net/timelines

https://www.songofamerica.net/composer/reinagle-alexander

https://www.songofamerica.net/composer/carr-benjamin

Strahan, D. 2015. Timothy Merrick House, Wilbraham Mass.

http://lostnewengland.com/2015/04/timothy-merrick-house-wilbraham-mass/

Updated 2020