Chief Pontiac, alerted of the English plan, broke camp to prepare for battle. All his warriors were painted for war and armed for combat.

***

At the end of July in 1763, and after peace was settled with the Wyandots and Pottawattamies, something noteworthy took place at Fort Detroit. The Ottawas and Ojibwas continued to closely watch the fort, while assailing it daily with trivial attacks. Meanwhile, unknown to the garrison, a strong re-enforcement was on their way to aid them. Captain James Dalyell left Niagara with 22 barges that carried 280 men with several small cannons, a fresh supply of provisions, as well as ammunition.

Extract from Manuscript Letter of Sir J. Amherst to Sir W. Johnson:

New York, 16th June, 1763.

I am to thank you for your letter of the 6th Instant, which I have this moment Received, with some Advices from Niagara, concerning the Motions of the Indians that Way, they having attacked a Detachment under the Command of Lieut. Cuyler of Hopkins’s Rangers, who were on their Route towards the Detroit, and Obliged him to Return to Niagara, with (I am sorry to say) too few of his Men.

Upon this intelligence, I have thought it Necessary to Dispatch Captain Dalyell, my Aid de Camp, with Orders to Carry with him all such Reinforcements as can possibly be collected (having, at the same time, a due Attention to the Safety of the Principal Forts), to Niagara, and to proceed to the Detroit, if Necessary, and Judged Proper.

2 Penn. Gaz. No. 1811

- Post Contents -

Captain James Dalyell

Drifting along the south shore of Lake Erie, Captain Dalyell’s troops soon reached Presqu’Isle where they encountered the scorched and battered blockhouse captured just a few weeks before. They were surprised to find mines and entrenchments made by the Indians during its siege of the blockhouse.

They proceeded on their voyage and reached Sandusky on the 26th of July. The troops went ashore and marched inland to the Wyandot village and burned it to the ground. They then set fire to the Wyandot’s corn fields and destroyed them.

Captain Dalyell and his troops then progressed northward for the mouth of the Detroit, reaching it cautiously on the evening of the 28th under the cover of night. “It was fortunate,” wrote Major Henry Gladwin, “that they were not discovered, in which case they might have been destroyed or taken, as the Indians, being emboldened by their late successes, fight much better than we could have expected.”

At dawn on the the 29th of July, the surrounding province near Detroit was shrouded by a thick fog – a known harbinger for a sweltry day – and by sunrise, the river’s surface began to pitch as the heavy fog gradually parted disclosing a dark and burnished body of water. The haze slowly moved fold upon fold, then its mist lightly drifted away to the forest’s margin where it dragged along the ground and clung to the grass tops.

For the first time, the garrison was able to see the approaching convoy, yet, they remained fearfully still should the convoy suddenly meet the same fate as the former detachment. Then a loud call from the fort to the convoy was quickly answered by a circular turn of the boats. Instantly, relief spread among the garrison.

The barges eventually reached the midway point in the river between the Wyandot and Pottawattamie villages, when the tribes opened a hot fire upon the boats from either shore. It was only two weeks prior that these Indians made a treaty for peace, but why they chose to end it was very suspicious (MS Letter – Major Rogers).

The convoy made quick circular turns with musketry firing and by the end of the engagement, 15 English troops were killed or wounded. When the skirmish ended and all danger subsided, the barges went to shore and its men landed amid cheers from the garrison.

Captain Dalyell’s detachment were soldiers from the 55th and 80th Regiments with 20 independent rangers commanded by Major Robert Rogers. Since the barracks in the fort were not large enough to house them, the troops were then all quartered with the inhabitants of the fort.

Not long after the troops resettled in their new quarters, a great smoke was seen from the Wyandot village across the river. Indians were seen paddling down stream with their household utensils and dogs. The fort presumed the Wyandots burned their huts and abandoned camp, but, actually, it was an Indian maneuver to set fires to some old canoes and other refuse piled in front of their village. After the warriors hid their women and children, they returned to the village and waited in the bushes hoping to ambush the English that might come within reach of their guns. Not a single English soldier was curious enough to be caught in their snare.

Time to strike a blow against chief pontiac

Captain James Dalyell was once a companion to Israel Putnam in some of the harrowing, adventurous passages Putnam experienced during his rough, veteran’s life. But now, Dalyell was aide-de-camp to Sir Jeffrey Amherst.

Upon arriving at Fort Detroit, Dalyell joined Major Gladwin in a conference where he strongly insisted the time had come for an irrecoverable blow be struck against Chief Pontiac. Dalyell requested permission to march out on the following night and attack the Indian camp. Gladwin was resistant to the attempt. He explained his experience with the current position of Indian affairs, and his cautiousness to proceed with Dalyell’s plan. But Dalyell strongly pressed his request until Gladwin yielded and gave his consent.

Extract from a MS Letter from Major Gladwin to Sir J. Amherst:

Detroit, Aug. 8th, 1763

On the 31st, Captain Dalyell Requested, as a particular favor, that I would give him the Command of a Party, in order to attempt the Surprizal of Pontiac’s Camp, under cover of the Night, to which I answered that I was of opinion he was too much on his Guard to Effect it; he then said he thought I had it in my power to give him a Stroke, and that if I did not Attempt it now, he would Run off, and I should never have another Opportunity; this induced me to give in to the Scheme, contrary to my Judgement.

Chief Pontiac decided it was necessary to relocate his camp several miles above the camp’s current position near the mouth of Parent’s Creek. The camp’s new spot was behind a great marsh which would provide protection for the Indian huts against the cannons of the vessel.

On the afternoon of July 30th, orders were issued to make preparations for a deliberate attack against Chief Pontiac’s camp. Unfortunately, carelessness of some officers enabled the plan to become known to a few untrustworthy Canadians.

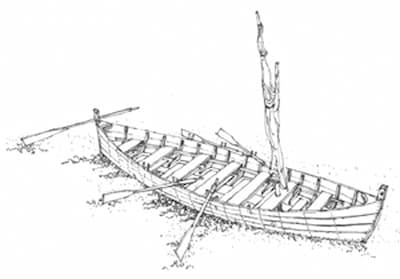

Bateaux = flat-bottom boats used widely during the 1700s

for moving troops and supplies

Two o’clock the next morning, July 31st, Fort Detroit’s gates quietly opened and Captain Dalyell’s detachment of 250 troops moved silently away from the fort. The men were filed two deep along the road while two large bateaux, each bearing a swivel on the bow, rowed up the river abreast of them. Lieutenant Brown led the advance guard of 25 men, while the center commanded by Captain Gray and the rear by Captain Grant. The men marched in lightweight garments through a night of heavy humidity and stillness.

Along their way was the Detroit river with its dark, glassy surface and endless sandy edge. To their left was a succession of Canadian houses, barns, orchards, and cornfields, including loud barking dogs that made sure the troops knew they were being watched. Roused from their sleep, the residents quickly looked out their windows to see English troops moving by land and water. A forewarning of danger.

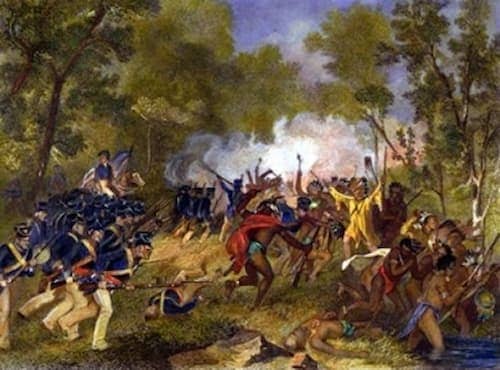

The British advanced toward their fight with little thought that Indian scouts were watching every step of their progress. Chief Pontiac, alerted by the Canadians of the English plan, broke camp to prepare for battle. Pontiac gathered all his warriors. They were painted for war and armed for combat.

Battle of bloody bridge

A mile and a half from Fort Detroit was Parents Creek. It descended through a wild and rough hollow, entering the Detroit River among overgrown grass and sedge grass. Not far from the river’s mouth, there was a narrow, wooden bridge where the road crossed to the other side. Beyond the bridge, the land rose in steep ridges parallel to the stream and along its summits were crude entrenchments done by Chief Pontiac to protect his old camp that previously occupied the area.

The Canadians built strong picket fences that enclosed their orchards and gardens as well as their piles of firewood that were shared by the neighboring houses. Behind the picket fences, wood piles, and numerous ditches crouched many Indian warriors with guns ready. Like a silent snake, they lay in wait for the approaching column of troops.

The British drew closer to the dangerous pass as evening faded into night. The expected bridge was barely visible and the often-mentioned house of Meloche could be somewhat seen up on the hill. The ridges beyond, however, could not be distinguished. Just a wall of total blackness. The British pushed forward.

The British advance guard were halfway over the bridge as the main body of the detachment began to enter the bridge, when a terrifying burst of screams came from the front of the bridge with Indian guns blazing in a general discharge. Half the advanced party were shot down, while shocked survivors recoiled with fear from the ambush.

Confusion quickly spread to the main detachment. The troops were frantic and they began retreating, but Captain Dalyell loudly raised his voice above the commotion as he pushed his way to the front rallying his men, bravely leading them forward into a counteroffensive.

The Indians overwhelmed the British with their next volley and again the British hesitated. Dalyell shouted above the turmoil and, in the madness of rage and fear, the troops charged full tilt across the bridge and up beyond the nearby heights. Not one Indian was in the heights to oppose them. The soldiers were enraged at this point as they wildly searched for the enemy in ditches and behind fences.

As the savages fled, their guns flashed through the thick gloom and their bellowing war cry went unabated. The British pressed forward in the pitch-black night. They were unfamiliar of the area and soon realized they were entangled in a maze of outhouses and enclosures. With every pause they made, the enemy renewed their attack by firing on the British front and flanks. Captain Dalyell decided it was useless to advance further. The only alternative was to withdraw and wait for daylight.

Captain Grant and his company recrossed the bridge and took up his station on the road. The rest followed, which was a small party that remained to keep the enemy in check while the dead and wounded were placed on board the two boats that rowed up to the bridge during the action.

This task was difficult to carry out during the gun volley across both sides. Heavy volleys were also heard from the rear where Captain Grant was stationed. A great force of Indians fired upon him from the house of Meloche as well as nearby orchards. Grant pushed up the hill and drove them at the point of their bayonets from the orchards. Grant also drove them from the house, whereby entering it, he found two Canadians inside.

The Canadians told Grant that the Indians were bent on cutting off the British from the fort and that they had gone in great numbers to occupy the houses that commanded the road below (Penn. Gaz. No. 1811; Detail of the Action of the 31st of July; Gent. Mag. XXXIII).

Grant and his men found behind the house a newly dug cellar that concealed a large number of Indians. These Indians ambushed the advancing troops and passed unmolested but when the rear came to counter their ambush, they raised a horrid yell and sent a barrage of gun shots against them. The troops almost fell into a panic. They looked to the river which ran close on their left and figured the only avenue of escape was along the road to the front. The troops started breaking ranks, pressing upon each other in blind eagerness to escape the deluge of bullets. But for the presence of Dalyell, the retreat would have been turned into a flight. The enemy marked Dalyell for his extraordinary bravery, especially after he already received two severe wounds.

Captain Dalyell’s operations did not slacken. He rebuked some of his soldiers and threatened others. He also beat some with the flat of his sword, until order was partially restored and their return fire to the enemy was effective.

Reclaiming settler houses from Chief pontiac’s Warriors

Daylight was rising, and a thick fog shrouded the ascending sun making it difficult for the troops to see the Indians. What they could see were the Indian guns flashing continuously amid the mist and hearing a multitude of Indian voices mingled in one dreadful yell that puzzled the men, and disrupted their functions to follow their leader’s commands.

The Indians took possession of a house and from its windows they fired upon the British. Major Rogers, with some of his provincial rangers, broke the door with an axe and rushed in, ousting the Indians. Captain Gray was ordered to dislodge a large party of Indians from behind neighboring fences. Gray and his company charged the Indians but he was struck down, mortally wounded. The British gave way for retreat since the Indians’ return fire was nearly diminished. Then, no sooner had the British turned to leave, when the Indians unexpectedly darted through the foggy mist and attacked the troops’ flank and rear. The Indians quickly cut down stragglers and scalped the fallen.

A little distance away, a sergeant of the 55th lay helplessly wounded. He desperately tried to raise himself up on his hands as he watched in despair after his retreating comrades. The sergeant’s plight caught Dalyell’s attention and he, heroically, ran out among the firing guns to rescue the wounded sergeant. A musket ball struck Captain Dalyell and he fell dead. Dalyell’s fate went undetected, and no one turned back to recover his body.

The surviving detachment pressed forward as the Indians harassed and pursued them. A greater loss of troops would have been more severe had not Major Rogers taken possession of another house that commanded the road and covered the retreat of the detachment.

Major Rogers and some of his Rangers entered the house, when many panic-stricken regulars rushed behind them seeking shelter from the Indians. It was a large house and it appeared to be a strong one as well. The neighboring women were found crowded in the cellar for refuge while some soldiers were in a frenzy to find places to hide. Other soldiers seized a discovered keg of whiskey from one of the rooms and drank it eagerly, while others piled packs of furs, furniture, and anything else within reach to barricade windows and doors.

The soldiers’ faces were dripping with sweat and blackened with gunpowder as they thrusted their muskets through every opening and fired ceaselessly on the whooping Indians. Occasionally, an enemy musket ball would enter through an unguarded crevice and strike a man down or bounce harmlessly against partitions.

Old Campau, master of the house, stationed himself on top of the trap door that led to the cellar where the women were hiding. He guarded the trap door from soldiers trying to seek shelter in the cellar. Suddenly, a musket ball grazed his gray head and buried itself in the wall. Screams of the women below, dreadful war whoops, shouts and curses of the soldiers all mingled to create a scene of loud and persistent confusion. It was a long time before Roger’s authority could restore order (John R Williams, Esq., of Detroit, a connection of the Campau family – particulars of the fight at the house of Campau).

Chief Pontiac’s warriors scatter and the British retreat

In the meantime, Captain Grant and his men moved ahead a half mile where orchards and enclosures were found that could be used as defense positions. It was decided they would wait there for the remaining troops from the center and rear to arrive. Grant detached all the men he could spare to occupy the houses below and when soldiers began to appear from the rear, his men would be able to reinforce those troops. Grant knew it was imperative to establish a complete line of communication with the fort before the retreat could be secured. Within an hour, the surviving detachment arrived with the exception of Major Rogers and his Rangers who were surrounded and trapped at Campau’s house by 200 Indians.

The two armed bateauxs finally returned after being sent down to the fort with the dead and wounded. Under orders from Captain Grant, the boats proceeded up the river to a strategic point opposite Campau’s house where they opened fire from their swivel guns, sweeping the grounds above and below. The Indians promptly scattered. Rogers and his Rangers emerged from the house and directly marched down the road to unite with Grant. The two boats followed Grant and Rogers closely while firing the swivel guns at the Indians to prevent any more attacks.

As soon as Major Rogers and his Rangers escaped Campau’s house, the enemy rushed in through another door to obtain scalps from the corpses left behind. An old squaw shuffled in behind the other Indians and stopped at one of the dead bodies. She lifted her withered face to the sky and let out a shrilling scream. She then took out a knife that was tucked inside her garments, bent over, and slashed open the dead body. Blood poured out and she scooped the blood between her cupped hands, drinking it with madness and delight.

After Major Rogers arrived from Campau’s house and reunited with Captain Grant, the retreat was resumed. They fell back from house to house, then were joined by parties sent by the garrison. There was a legion of Indians in the distance that stood whooping and yelling, unable to strike. Grant’s well-chosen positions enabled him to calmly and safely maneuver the troops through the final stages of retreat. After six hours of marching and small skirmishes, the detachment finished their mission and entered the sheltering palisades of Fort Detroit.

***

At the Battle of Bloody Bridge, the British had 59 casualties – killed and wounded. Indian loss was never determined, however, it most likely did not exceed 15 or 20. Indian numbers were probably inferior compared to the British at the beginning of the fight. Reportedly, fresh parties were continually joining them until there were seven or eight hundred warriors participating.

The Ojibwas and Ottawas alone formed the ambush at the bridge under Pontiac’s command. The Wyandots and Pottawattamies arrived later to the scene of action because they had to cross the river in canoes and pass around through the woods behind Fort Detroit in order to be a part of the fight (MS. Letters – MacDonald to Dr. Campbell, August 8th; Gage to Lord Halifax, October 12th; Amherst to Lord Egremont, September 3rd; Meloche’s Account, MS.; Gouin’s Account, MS.; St. Aubin’s Account, MS.; Peltier’s Account, MS.; Maxwell’s Account, MS.; etc.).

In the Diary of the Siege is the following, under the date of August 1st:

Young Mr. Campo (Campau) brought in the Body of poor Capt. Dalyell about three o’clock to-day, which was mangled in such a horrid Manner that it was shocking to human nature; the Indians wip’d his Heart about the Faces of our Prisoners.

According to European warfare during the 1700s, the conflict at Bloody Bridge would have been considered a simple skirmish with American savages. However, this conflict was raised to importance because it was a pitched battle; meaning the location of the battle was not a chance encounter – the soldiers and warriors fought in close contact.

The Indians were elated by their success. Runners were dispatched several hundred miles as well as through their surrounding woods to spread their victorious news. Indian re-enforcements began to arrive and join the force of Pontiac. Major Gladwin wrote: “Fresh warriors arrive almost every day, and I believe that I shall soon be besieged by upwards of a thousand.”

The English were well prepared for resistance. The fort’s garrison embodied more than 300 experienced men and there was no doubt in anyone’ mind that they would be successful defending the fort. Day after day passed with only a few, small skirmishes and just a few men killed. Then on the night of September 4th, a most memorable feat was achieved.

The schooner Gladwyn, smaller of the two armed vessels previously mentioned, was sent down to Niagara with letters and dispatches. On the boat’s return trip, on board was Horst (master), Jacobs (mate), a crew of 10 men who were all backwoodsmen. Also aboard were six Iroquois Indians who were supposed friends of the English. On the night of September 3rd, the Gladwyn entered the River Detroit. By morning, the six Indians asked to be set on shore; a request foolishly granted. The Iroquois disappeared into the woods and reported to Pontiac’s warriors the small number of the boat’s crew.

The Gladwyn stayed up the river until nightfall when the wind weakened, then it was forced to anchor nine miles below the fort. The men on board were on guard and on high alert for any sign of danger. As night fell, their vigilance intensified as they suspected every sound that broke the stillness; a strange cry from a night hawk or the bark of a fox from the woods on shore. There was complete darkness and nothing further than a few rods could be discerned.

Meanwhile, 350 Indians in birch canoes silently glided down the current and closed in on the Gladwyn before they were seen. The men on board the boat only had enough time to load and fire a single cannon shot before the Indians were beneath her bows and climbing up the boat’s sides holding knives clinched between their teeth.

The crew gave the Indians a close fire from their muskets, without any effect. Immediately, they threw down their guns and seized spears and hatchets which they were all provided. Then swiftly met the enemy with such furious energy and courage that, in the space of two or three minutes, they killed and wounded more than twice their own number. But the Indians were only slowed for a moment. The master of the vessel was killed, several of the crew were disabled, and the enemy was leaping over the bulwarks when Jacobs, the mate, quickly called out to blow up the Gladwyn. This desperate command saved the boat and its crew.

The Wyandots, who gained the deck, understood the meaning of the mate’s command and quickly gave an alarm to the rest of the Indians to leave the ship. Every Indian panicked by jumping overboard or diving into the water and swimming as fast as they could in all directions to escape the expected explosion.

The Gladwyn was safely cleared of the enemy who did not renew another attack. The following morning, the schooner sailed for the fort which it reached without further hostility. Six of the crew escaped unhurt and, of the remainder, two were killed and four seriously wounded. The Indians had seven warriors killed immediately and nearly 20 wounded, eight of whom were known to have died within a few days afterward.

Though the attack was brief, the fierceness of the fight was sufficiently apparent from the loss on both sides. According to an eye-witness who was present on the crew’s return to the fort said, “The appearance of the men was enough to convince every one of their bravery. They being as bloody as butchers, and their bayonets, spears, and cutlasses blood to the hilt.” The crew survivors courage was awarded as deserved (MS. Letter-Gladwyn to Amherst, Sept.9. Carver,164; Relation of the Gallant Defence of the Schooner near Detroit, published by order of General Amherst, in the New York papers; Penn. Gaz. No.1816; MS. Letter-Amherst to Lord Egremont, Oct.13.; St. Aubin’s Account; MS. Peltier’s Account; MS. Relation of some Transactions at the Detroit in Sept. and Oct.1763, MS).

***

Epilogue

The Commander-in-chief ordered a medal to be struck and presented to each of the men. The mate of the schooner, Jacob, was found to be as foolhardy as he was brave. Captain Carver remarked that several years after the Fort Detroit incident, when in command of the same vessel, Gladwyn, he went lost with all his crew in a storm on Lake Erie. It was unfortunate that Jacob stubbornly refused to take in enough ballast.

As we now take leave of Detroit’s garrison, whose fortunes we followed for so long, we will turn our attention to the progress of events in the quarter of the wilderness still wild and remote…

***

Part 5 – Massacre at Fort Michillimackinac, 1763

***

Reference

I decided to use Francis Parkman’s THE CONSPIRACY OF PONTIAC as my sole reference and guide for the Parts that followed Part 1. Parkman’s version gave me a much clearer window into the actual historical events, its characters, human behavior, strategies and tactics that I found dependable overall … even 200+ years later. I wanted to understand Pontiac: his character, motives, and beliefs. I wanted to know the indigenous force of the American Indian and their historical significance: their way of life, drama, ambition, and savagery. I wanted to share a story, not just an article of facts.

Parkman, Francis. THE CONSPIRACY OF PONTIAC (1851). Collier Books, New York, NY (1962)