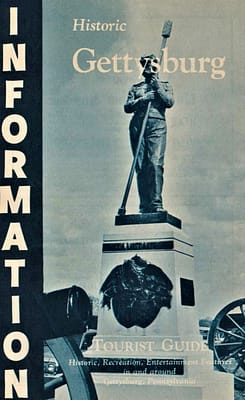

Gettysburg was the site of America’s greatest battle. It marked its 150th anniversary in 2013. In 1964, when I was eight, my family and I visited the battlefield (est. 1895) in Pennsylvania for its centennial anniversary. My visit there changed my perspective on American history forever. I was old enough to understand that the American Civil War was fought between the North against the South, brother against brother, and it ended in massive casualties on both sides. It was the bloodiest battle ever fought on American soil.

- Post Contents -

town of gettysburg – 1863

Gettysburg was named for James Gettys, a site granted to him by William Penn, and is situated in southern Pennsylvania near the Maryland border. The town of Gettysburg, in 1863, was a hub of 10 major crossroads and a growing population. The probability of an army passing through was very high, and a military engagement between opposing armies inevitable. Thus, when the Union Cavalry came across a Confederate infantry on the outskirts of Gettysburg, a warning shot was fired and the doorway to hell opened for the damned onslaught of American kinfolk.

The first day of battle ranked 12th as the bloodiest of the Civil War, having more casualties than the combats of Bull Run and Franklin combined. The second day of fighting ranked 10th as the bloodiest of the Civil War with casualties more extensive than those at the larger Battle of Fredericksburg. The battle killed more general officers than any other. The Battle of Gettysburg paid the highest human-life cost of the Civil War.

(Note: I found the total number of lives lost, wounded, and missing for Confederate and Union armies differed among the various sources in my research. Numbers did not match on any site or book, so I rounded the casualty numbers for both above 20,000.)

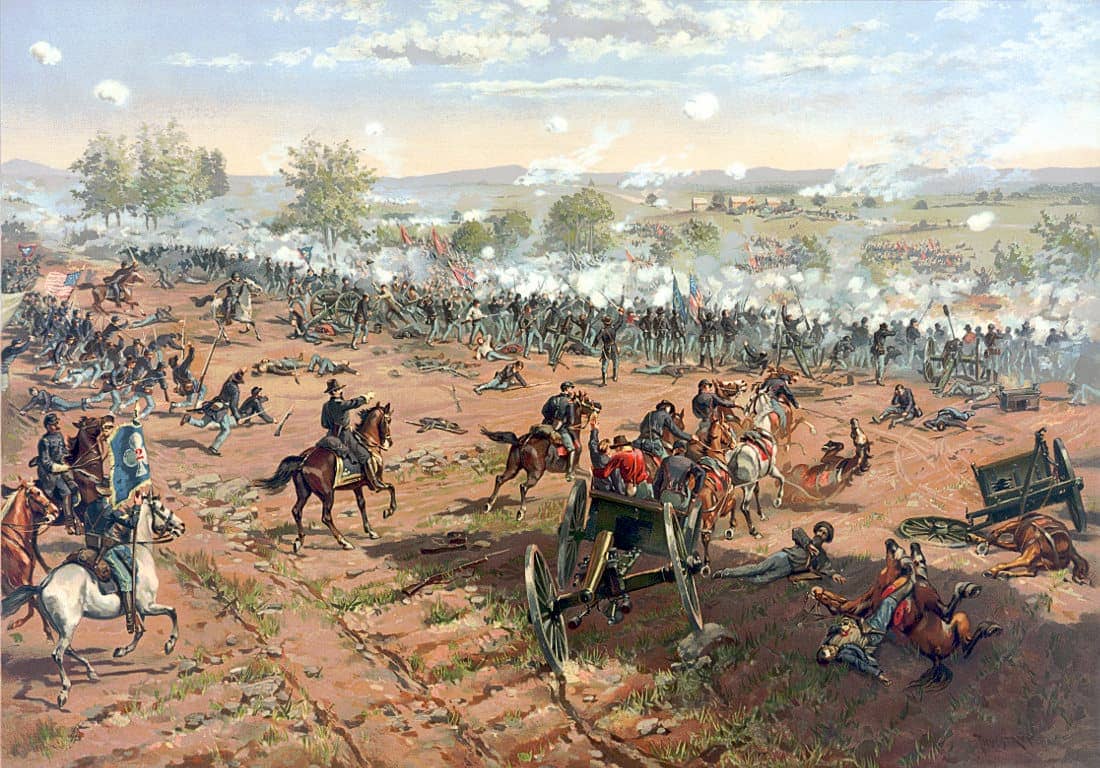

BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG –1863 – HELL ON EARTH

“The hoarse and indistinguishable orders of commanding officers, the screaming and bursting of shells, cannister and shrapnel as they tore through the struggling masses of humanity, the death screams of wounded animals, the groans of their human companions, wounded and dying and trampled underfoot by hurrying batteries, riderless horses and the lines of battle…a perfect hell on earth, never, perhaps to be equaled, certainly not to be surpassed, nor ever to be forgotten in a man’s lifetime. It has never been effaced from my memory, day or night, for fifty years.”

Massachusetts Private, Gettysburg – The Civil War: an Illustrated History

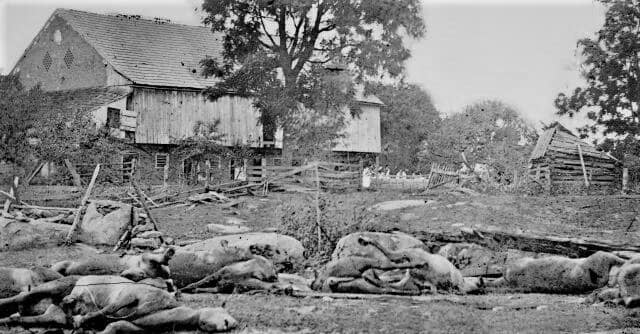

dead artillery horses and where many Union and Confederate dead were buried

IN SEARCH OF SUPPLIES

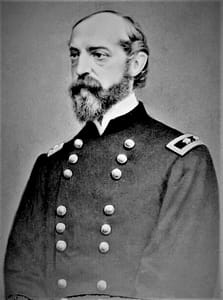

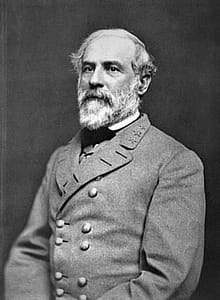

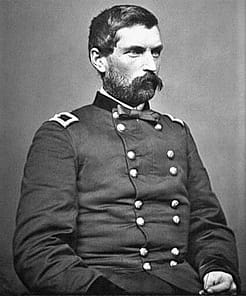

Union forces under General George G. Meade eventually defeated the Confederates commanded by General Robert E. Lee in the three-day battle. Yet the commanding generals never meant to fight in Gettysburg.

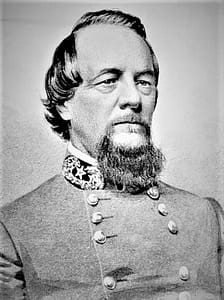

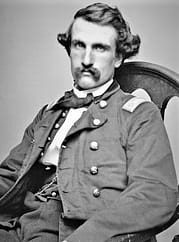

Union Army of the Potomac

archives.gov

Confederate Army of Northern Virginia | Library of Congress

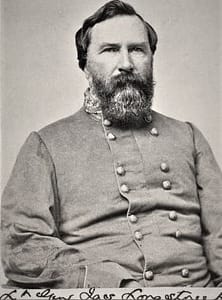

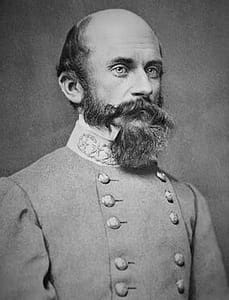

In search of needed supplies, Lee’s army invaded the North by entering southeastern Pennsylvania where he was able to freely roam the territory. His main army was spread too far and wide to engage in battle (General James Longstreet in Chambersburg and General Ambrose P. Hill were eight miles to the east, and Lieutenant General Richard Ewell at York and Carlisle), and as long as Meade’s army remained south of the Potomac River, his invasion could do no harm. However, Lee’s action alarmed the government in Washington of impending danger.

Library of Congress

(1825-1865) | archives.gov

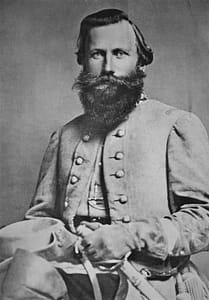

Unexpectedly, General Lee became separated from his cavalry, which was under General J.E.B. Stuart, for three days. As a result, General Lee was unable to determine the strength and movement of the enemy. When General Lee found out that the Union forces were now concentrated north of the Potomac River, he ordered his three army corps under Longstreet, Ewell, and Hill to change their positions for Gettysburg. Lee then took up a strong defensive position along the eastern slope of South Mountain, near Cashtown, and General Meade focused his forces on a defensive position behind a stream called Pipe Creek in northern Maryland, some 15 miles south and eastward of Gettysburg.

(1817-1872) | americancivilwar.com

Library of Congress

gettysburg – 1 JULY 1863

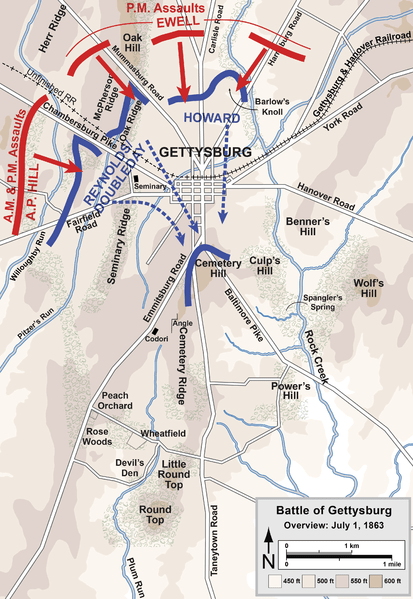

At 5:30 a.m., Corporal Alpheus Hodges, Company F, 9th New York Cavalry, along with three companions, were five miles west of Gettysburg searching for the enemy through the morning mist along Cashtown Road. It wasn’t long before he saw one, Colonel Birkett Davenport Fry’s 13th Alabama Infantry, heading his way. Another advancing Confederate brigade of A.P. Hill’s Corps was under General James J. Archer. Corporal Hodges fired a shot, then he galloped as fast as his horse would take him back to General Buford to report his encounter.

(1822-1891)

American Civil War Museum | geni.com

civilwarprofiles.com

civilwarprofiles.com

(Note: One of my several library sources on this subject [J. MacDonald – Great Battles of the Civil War] stated that a Lt. Marcellus E. Jones of the 8th Illinois Calvary had seen the Rebel troops advance up Chambersburg Road toward his post east of Marsh Creek. It said that Lt. Jones fired the first shot in the Battle of Gettysburg. I also noticed another statement from the same source that Hancock had replaced the fallen Reynolds, and my other sources contradict this information. I referred to my other sources.)

General Hill’s corps met the Federal cavalry force under Buford west of Gettysburg. The Union cavalry was driven back, including the Union’s 1st Corps under General J.F. Reynolds. General Reynolds was an instinctive fighter and as he and his troops surged forward at the battle line to strike, a minie ball struck him in the neck and he fell dead from his horse. There was no other choice now for General Lee or General Meade but to fight.

civilwarprofiles.com

(1819-1893)

civilwarprofiles.com

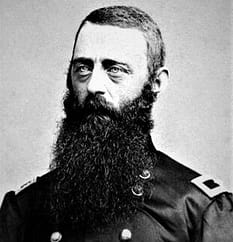

General Oliver Otis Howard

(1830-1909)

civilwarprofiles.com

General Abner Doubleday moved up to command Reynolds troops. He extended the Union’s 1st Corps along the crest of their ridge, facing west, to stand against a new attack. They were surprised to come under fire from the north as Lieutenant General Ewell’s leading division attacked Doubleday’s right and rear. General Oliver Otis Howard‘s Union brigade, though low in number, arrived just in time to ward off Ewell’s assault. Then Ewell’s second division came into action from the northeast and hit Howard’s line in the flank and rear, striking precisely at the right moment but quite by accident. If Howard’s troops were driven back, General Doubleday’s troops would not have been able to hold their ground against General Hill. This was General Lee’s moment of opportunity, and he immediately did an about-face and ordered an advance.

Meanwhile, Confederate General Archer was captured and taken prisoner. He was the first general officer in the Army of Northern Virginia taken by the Federals since General Lee assumed command of the Confederate Army. General Doubleday was pleased to greet an old friend, but General Archer did not consider the meeting a pleasure.

As General Lee advanced, a desperate fight commenced on an open field for almost an hour. The Union’s line right half collapsed first in the front, then at the flank, and then in the rear from the Confederate offensive. The Union troops were overwhelmed, and General Howard’s men broke off and retreated to the town of Gettysburg, where they were trapped. Their flight into town proved to be confusing and costly. Union and Confederate troops collided quite unexpectedly, sending intervals of smoke from blasting canisters down Gettysburg streets. Dilger’s Union Ohio Battery defended the troops from the town square in an effort to halt the advancing Confederates, and by end of day, the Union troops managed to get to Cemetery Hill. Lieutenant General Ewell’s triumphant Confederates held the town.

(1824-1886) | archives.org

Later that afternoon, General Meade sent Major General Winfield Scott Hancock to take charge and rally the retreating troops into a new battle line along Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill. Major General Hancock anticipated the Confederates to push their advantage, but they did not. General Meade found his army to have a strong defensive position from Culp’s Hill southeast of Gettysburg, west to Cemetery Hill, and two miles south along Cemetery Ridge to a rocky mound called Little Round Top. General Meade surmised that he had enough men to hold their position, and that possibly he could move with an offensive himself.

General Lee viewed the fight on the first day a win for the Confederates; however, time and circumstances went against him. The Federal Army for the first time in this war defended its own soil. Lee did not have the defensive position that had served him well at Antietam and Fredericksburg or the trickery and distractions that won the Seven Days and Chancellorsville. Lee did not have the advantage, and he could not force the Federals to fight this battle on his terms. The only maneuver left was to continue the fight and slug it out, a position General Lee did not want.

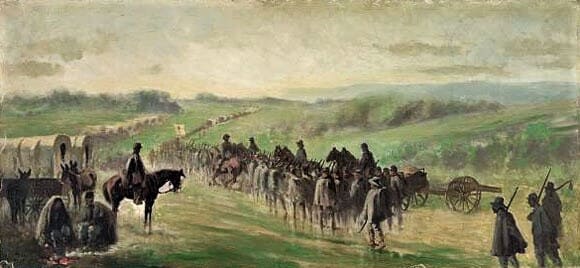

Gettysburg – 2 JULY 1863

“Middletown, Md., July 2nd 1863–On the night of July 1st we were camped near Manchester, Md. Rumors of fighting in Pennsylvania have been heard all the days, but the distance was so great to the battle [Gettysburg] that we knew little about it. The men were tired and hungry and lay down to rest early in the evening. At nine o’clock orders came for us to move and we in great haste packed up and started on the road towards Pennsylvania…. We struggle on through the night, the men almost dead for lack of sleep and falling over in their own shadows. But we go on in the warm summer night…. On the morning of July 2nd we heard firing in front and then we understood the reason for such great haste…. The firing in our front grew loud and more distinct and soon we met the poor wounded fellows being carried to the rear….At about 2 o’clock P.M we reached the Battlefield of Gettysburg, Penn. having made a march of thirty-four (34) miles without a halt. The men threw themselves upon the ground exhausted, but were soon ordered forward. We followed the road blocked with troops and trains until 4 P.M when the field of battle with the long lines of struggling weary soldiers burst upon us. With loud cheers the old Sixth Corps took up the double quick and were soon in line of battle near the left of the main line held by the 5th Corps…. when we were relieved and returned a short distance. The men threw themselves upon the ground, and oblivious to the dead and dying around us we slept the sleep of the weary.“

Robert Hunt Rhodes, ed., All for the Union: The Civil War Diary and Letters of Elisha Hunt Rhodes (New York: Orion Books, 1991). Copyright 1991, Robert Hunt Rhodes. | 2nd Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry – his unit, a group within the VI Corps under General John Sedgwick in Eustis’ Brigade

Elisha Hunt Rhodes

(1842-1917)

2nd Rhode Island Volunteers,

Company B | pbs.org

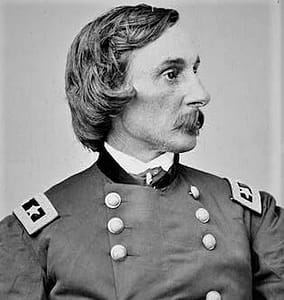

Commander First and Second U.S. Sharpshooters

–Created unit of elite civilian marksmen, equipped with the accurate Sharps Rifle, which proved to be a powerful asset to the Army of the Potomac–

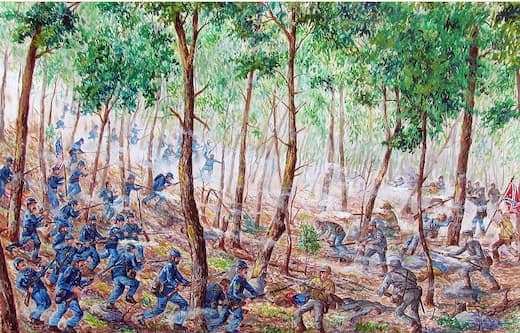

In the Woods – Tom Lovell | arcgis.com

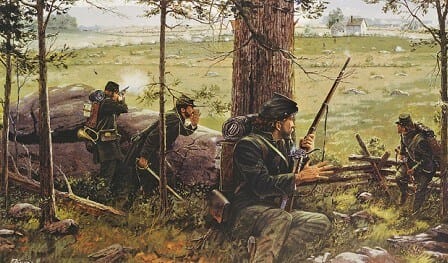

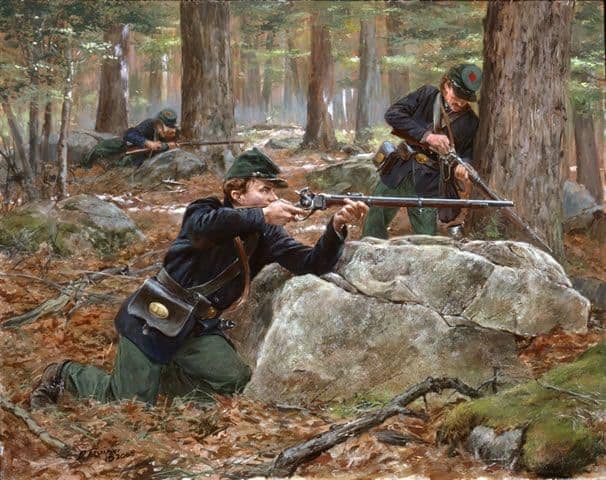

“About 7.30 a.m. I received orders to send forward a detachment of 100 sharpshooters to discover, if possible, what the enemy was doing. I went out with the detail, and posted them on the crest of the hill beyond the Emmitsburg road, and where they kept up a constant fire nearly all day upon the enemy in the woods beyond until they were driven in, about 5 p.m., by a heavy force of the enemy, after having expended all their ammunition. As it was impossible with this force to proceed far enough to discover what was being done by the enemy in the rear of this woods, I reported the fact to Major-General Birney, and about 11 a.m. I received an order from him to send out another detachment of 100 sharpshooters farther to the left of our lines, and to take the Third Maine Volunteers as support, with directions to feel the enemy, and to discover their movements, if possible.’

“I moved down the Emmitsburg road some distance beyond our extreme left and deployed the sharpshooters in a line running nearly east and west, and moved forward in a northerly direction parallel with the Emmitsburg road. We soon came upon the enemy, and drove them sufficiently to discover three columns in motion in rear of the woods, changing direction, as it were, by the right flank. We attacked them vigorously on the flank, and from our having come upon them very unexpectedly, and getting close upon them, we were enabled to do great execution, and threw them for a time into confusion. They soon rallied, however, and attacked us, when, having accomplished the object of the reconnaissance, I withdrew under cover of the woods, bringing off most of our wounded, and reported about 2 o’clock to Major-General Birney the result of our operations and discoveries.’

“The Second Regiment was deployed in front of the Second Brigade, by order of General Ward, and moved forward to a favorable position, where they held the enemy’s skirmishers in check and did good execution, breaking the enemy’s front line three times, and finally fell back as the enemy advanced in heavy force, remaining in action with the remainder of the brigade during the engagement. The balance of the First Regiment, under the immediate command of Captain Baker, moved forward to the right of the peach orchard, on the right of the First Brigade, where they had a splendid chance for execution, the enemy coming forward in heavy lines. I relieved them from time to time as they exhausted their ammunition.”

Report of Col. Hiram Berdan, Commanding First and Second U.S. Sharpshooters at the Battle of Gettysburg to Capt. F. BIRNEY, Assistant Adjutant-General for 2 July 1863 | report dated: 29 July 1863

Dale Gallon | Late Afternoon – Big Round Top East of Slyder Farm | berdansharpshooters.com

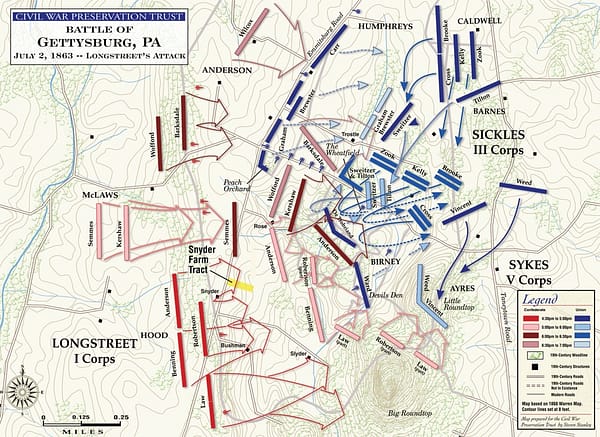

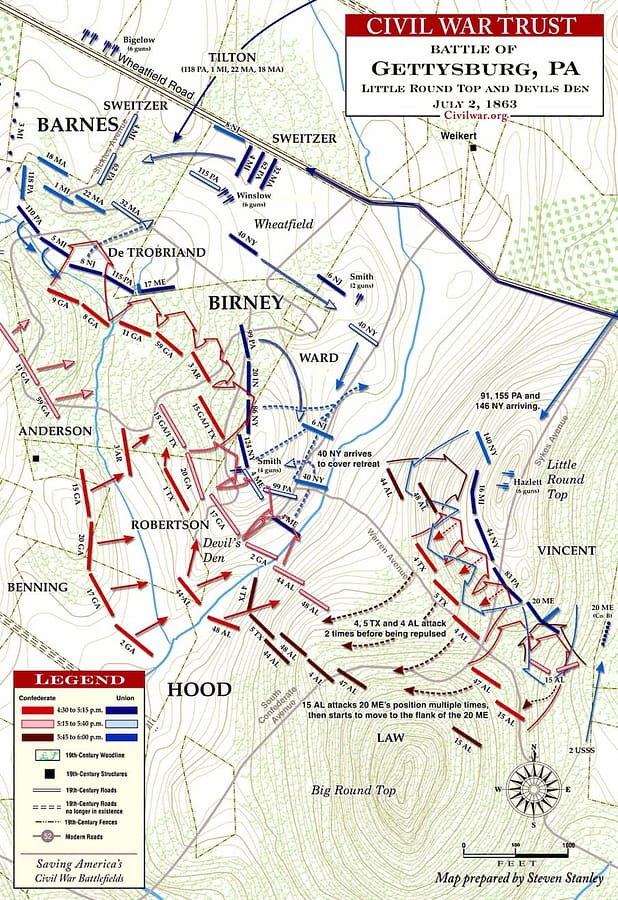

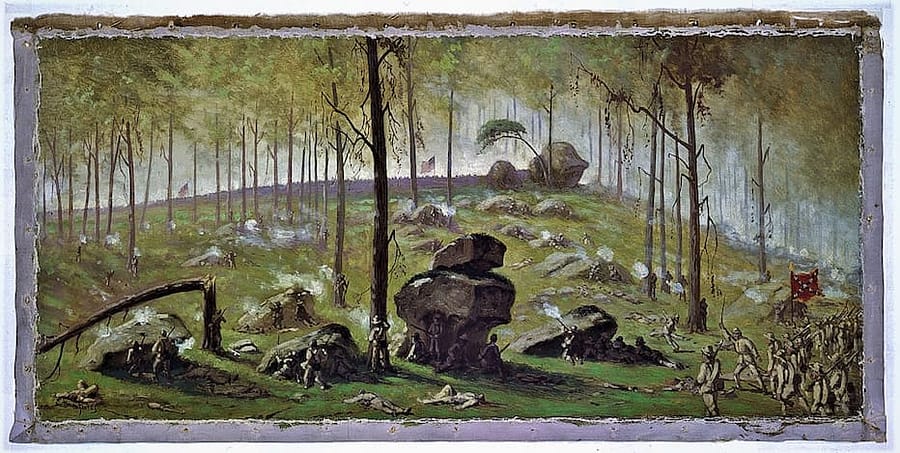

The Confederate attack was not made until late in the afternoon, which provided time for the Federal forces to strengthen their position and prepare for an attack. General Daniel E. Sickles moved the Union III Corps from its position on lower Cemetery Hill toward the Peach Orchard, south of Gettysburg and a half mile in front of the Union line. This move left the Round Tops and the Union’s left flank undefended. General Meade ordered him to fall back, but before General Sickles could do so, he met General Longstreet’s Confederates at the Peach Orchard where he attacked. They fiercely fought in the Peach Orchard, a wheat field, and in the rock ravines known as Devil’s Den. A dense fog of gun smoke hid the fields, the woods, the fighting men, and the cannons whose gunners found this fight to be worse than Antietam, a battle remembered as Artillery Hell.

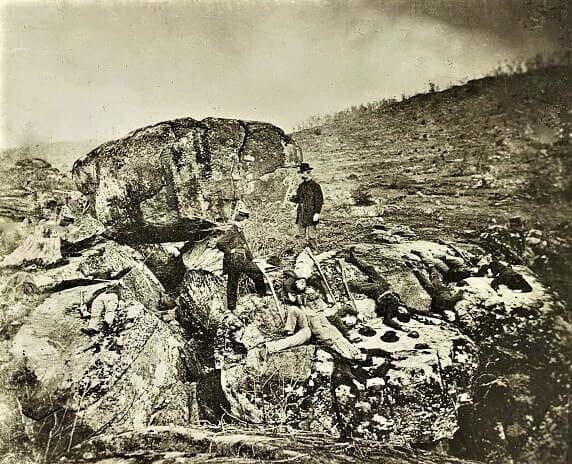

Confederate dead | 1863 | Library of Congress

Gettysburg museum of history

battlefields.org

civilwarprofiles.com

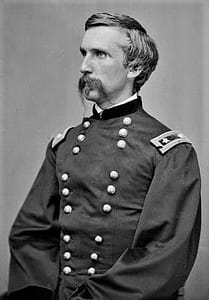

The Union’s Chief Engineer, General Gouverneur K. Warren, and a young engineer, Lieutenant Washington A. Roebling, were sent to the summit of Little Round Top to view the battle and they found it undefended. They saw below that Sickles was unable to move in the Peach Orchard, and Longstreet was moving around to the Union’s left. Warren sent for reinforcements for Little Round Top, and the last of four regiments ordered in was the 20th Maine, under Lieutenant Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain.

by Philip Lee | fineartamerica.com

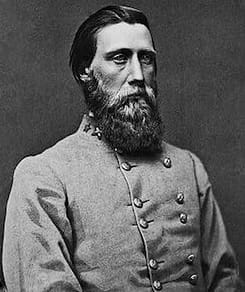

The Fighting 20th Maine prevented the Confederate Texas Brigade from flanking Little Round Top. The Confederates regrouped and struck again, gaining some ground and threatening the Union’s left. Chamberlain reformed his line into right angles and had his men continuously fire their muskets the whole time. Physically drained from repelling repeated assaults from the Confederates, who were commanded by Major General John B. Hood, and depleted of all their ammunition, Chamberlain advanced his men with bayonets fixed. He held the right of his regiment straight and sent his left lunging down the hillside to the right. They surprised the Confederates, who faltered, scattered, and fled for their lives.

(1831-1879)

civilwarprofiles.com

“Imagine if you can, nine small companies of infantry, numbering perhaps three hundred men, in the form of a right angle, on the extreme flank of an army of eighty thousand men, put there to hold the key of the entire position against a force at least ten times their number…”

Private Gerrish“At times I saw around me more of the enemy than of my own men…squads of stalwart men who had cut their way through us…”

Lieutenant Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain (recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor)“We ran like a herd of wild cattle…As we ran, a man…to my right and rear had his throat cut by a bullet, and he ran past me breathing at his throat and the blood spattering…My dead and wounded were then nearly as great in number as those still on duty. They literally covered the ground…the blood stood in puddles in some places on the rocks: the ground was soaked with blood.“

Colonel Oates, Confederate soldier

The Confederates defeated the Federal position at Peach Orchard, but Colonel Chamberlain’s forces were able to defend two very important positions, Round Top and Little Round Top.

Combat at Peach Orchard, Devil’s Den, and Little Round Top ended with General Meade risking exposure of the Union lines at Cemetery Ridge by moving more troops to stop General Longstreet’s Corps from crushing the Union Army’s left. The Confederates quickly acted, and they moved to break through the opening. They advanced in waves, brigade after brigade, and smashed their way onto Cemetery Ridge. The Confederates were now not far from the rear of the Union line, but General Hancock pushed back the Confederates with Union reserves. One of those Union reserve regiments was the 1st Minnesota, which lost most of its men in less than five minutes. The 1st Minnesota had the most casualties compared to any Union regiment in the war.

By nightfall, Hoke’s North Carolina Brigade and Hays’ Louisianans fought their way to the crest of East Cemetery Hill, while more Confederates attacked at the same time on the north side of the slope. The units of Hoke and Hays heard troops approaching them in the darkness, and they held their fire believing their support troops had arrived. Unfortunately, the approaching troops in the dark were Union troops and by the time they figured out who they were, it was too late for the two Confederate brigades and they were driven from the hill.

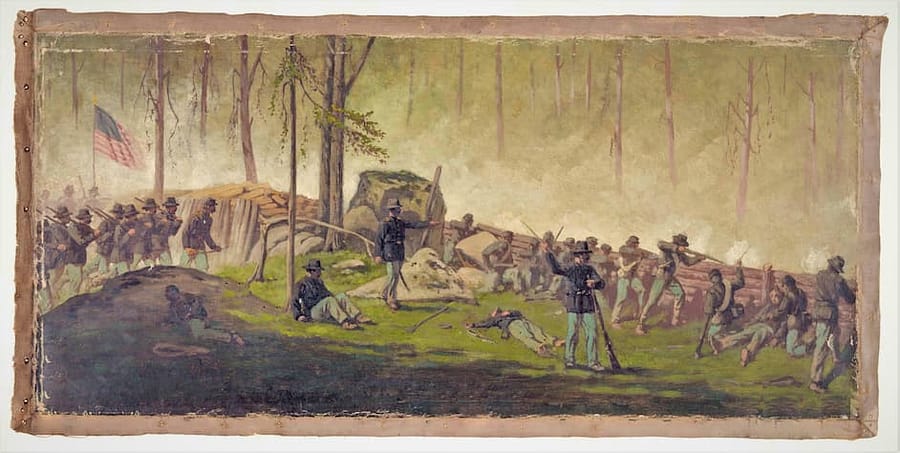

on Culp’s Hill | by Edwin Forbes | nps.gov

Meanwhile, at Culp’s Hill, Confederate General Edward Johnson attacked up the hill against the Union brigade, the upstate New Yorkers, led by 63-year-old General George S. Greene. The Confederates were astounded that only one brigade could defend and hold such an important position.

Edward “Allegheny” Johnson (1816-1873)

battlefields.org

“I saw the surgeons hastily put a cattle horn over the mouths of the wounded ones, after they were placed upon the bench. At first I did not understand the meaning of this but upon inquiry, soon learned that that was their mode of administrating chloroform, in order to produce unconsciousness. But the effect in some instances were not produced; for I saw the wounded throwing themselves wildly about, and shrieking with pain while the operation was going on.”

At Gettysburg, or What a Girl Saw and Heard of the Battle – Matilda “Tillie” Pierce Alleman, 1889. Born 1848 in Gettysburg, she was 15 years old in 1863 during the battle.

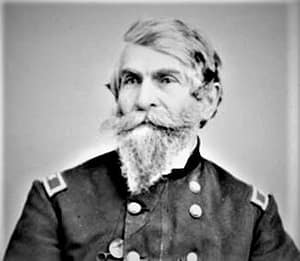

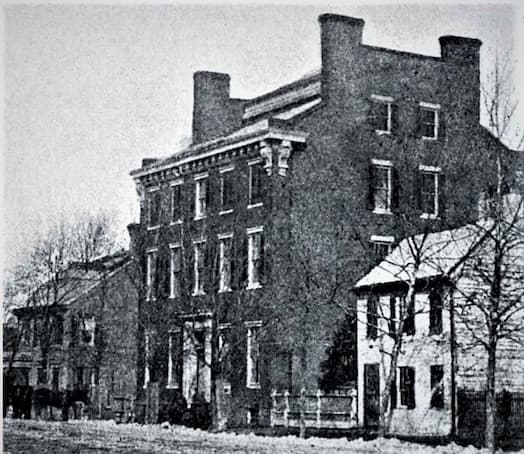

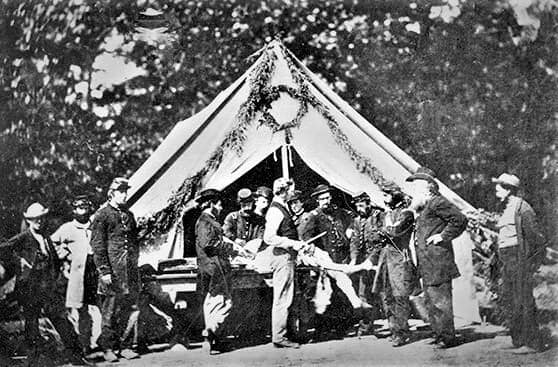

gettysburg – Civil War hospital and medical system

America’s early hospital and medical system was completely unprepared for the massacre of human and animal life by the Minié-ball bullet and the rifled cannon unleashed during the Civil War. Immense casualties from the war’s first battles doomed the old school way of medical understanding and readiness, sending doctors on both sides into turmoil. At the start of the war, there was no organized ambulance system to remove casualties from the battlefields or a mobilized system of medical treatment for the wounded. Many of the wounded remained on the battlefields up to three days. Quick arrangements for field hospitals were produced through local homes, churches, businesses, and other structures refitted to treat, quarter, and manage all Union and Confederate wounded and sick.

(1824-1872)

Reynolds-Finley Historical Library

Reynolds-Finley Historical Library

In 1862, newly-appointed Union Surgeon General, Dr. Alexander Hammond, and his medical director, Jonathan Letterman, MD, developed an ambulance and hospital system that became a standardized operation for the American military for wounded care and delivery over the next 80 years. Their organization consisted of trained hospital personnel to be used in medically-equipped places such as field, wagon, brigade, general, as well as specialty and rehabilitation hospitals. In order for these new medical standards to be met and implemented, Dr. Hammond hired prominent physicians within the United States as Medical Inspector Generals to examine the care and sanitation standards for each hospital. By July 1863, tent hospitals by the hundreds were made ready in advance and quickly assembled at battlefields, such as Gettysburg.

Gettysburg – 3 JULY 1863

Gettysburg National Park, Eurographics

At dawn, more Union troops moved into the area of Culp’s Hill then later that morning, the battle resumed. Shooting continued endlessly from midday till after sunset. Though the Confederate sharpshooters endured the magnitude of the fight on Culp’s Hill, they found if they climbed nearby tall trees for higher points to overlook Federal defense positions, they could find weak spots and advantages. However, the Union troops on Culp’s Hill, in particular the 12th Corps, named these gray spies “tree frogs,” and the soldiers were always pleased whenever such a tree frog was shot from his perch and fell. A Union soldier from the 28th Pennsylvania recalled when one such Confederate sharpshooter was spotted from a high tree branch, and the Federals knew the sharpshooter’s position guaranteed him a dead Union soldier with every shot. So a nearby Federal quickly aimed his rifle at the sharpshooter before he was spotted and fired, felling the Confederate sharpshooter head first.

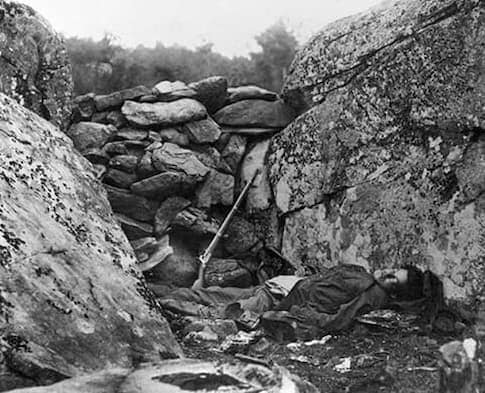

by Edwin Forbes | nps.gov

“Mr. Reb came down head first, striking a large boulder that had been split . . . in such a manner that his head entered the crevice, his shoulders striking either side, and being crushed, he was wedged in so tightly, with feet extending upward, that it was utterly impossible to extricate his body for burial [the] next day.”

Private Henry Brown of Company A: H. E. Brown, The 28th and 147th Regiments Penna. Vols. At Gettysburg, (n.d.), 6, vertical file, GNMPL

berdansharpshooters.com

“On the 3d, a detachment of about 100 sharpshooters was sent, under command of Captain Baker, as sharpshooters, to cover the front of the Sixth Corps. They remained there all day, constantly firing, and toward night advanced, driving the enemy’s skirmishers some distance, and capturing 18 prisoners. The balance of the command was moved toward the right with the rest of the division, to the support of some batteries, where nothing of importance occurred.”

Report of Col. Hiram Berdan, Commanding First and Second U.S. Sharpshooters at the Battle of Gettysburg to Capt. F. BIRNEY, Assistant Adjutant-General for 3 July 1863 | report dated: 29 July 1863

After several hours of hard fighting, the Confederates were driven back down to the plain below the hill, battle weary and weakened. The Union right was out of danger. General Longstreet tried hard pushing back General Sickles’ Corps but failed to take Little Round Top, which would have enabled him to direct the gunfire from a flanking position along the length of the Union’s entire position.

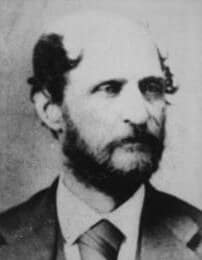

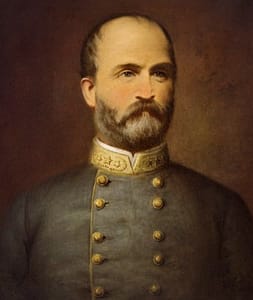

At this point, General Lee had to attack the Union lines since his army was unable to break their end lines the day before. He immediately mandated an artillery bombardment for two hours against Cemetery Hill and Cemetery Ridge. He then ordered General Longstreet’s Corps to inflict a direct strike on the Union center at Cemetery Ridge with three divisions: General George E. Pickett, Brigadier General J. Johnston Pettigrew, and Major General Isaac R. Trimble.

George Edward Pickett

(1825-1875)

civilwarprofiles.com

ncpedia.org

Isaac Ridgeway Trimble

(1802-1888)

civilwarprofiles.com

Meanwhile, General Meade, commander of the Union forces, anticipated General Lee’s move and readied his army for the attack. He alerted General John Gibbon, Commander of the 2nd Corps, who was already positioned at the center of the Union line, to expect the Confederates. At 1 p.m., the Confederates delivered a barrage of 138 cannons of heavy artillery directly at the Federal line, and the Union responded with nearly 100 artillery guns. This became known as the greatest artillery duel in the history of the North American continent.

civilwarprofiles.com

Each army launched a shower of iron balls, shells, and canisters at each other hoping to gain an advantage to turn the tide of the Gettysburg Battle. But the Union prevailed by remaining steadfast in their defensive position. This greatly troubled General Lee, not being able to unstabilize the Union position. General Lee saw no other choice but to send 12,000 troops across open fields that stretched for a mile. It was a risky move, but the only way he could turn the odds in his favor.

The sound of the bombardment was like a roar that went unbroken for a long time. It was sustained by loud and endless musket fire. Within one square mile, more than 200 artillery guns were in action launching two or three rounds a minute. The noise was powerful and dreadful. Some gunners said afterward that they could hardly hear the cannon that they were firing.

The infantry hugged the ground in order to be as low and as small as possible. Rocks shattered from artillery guns into deadly, jagged projectiles that struck the soldiers on Cemetery Hill. In the woods, trees were smashed into splintered pieces that killed many Confederates waiting there. Then the bombardment ended, and an eerie silence enveloped the smoking field. This became known as the greatest artillery duel in the history of the North American continent.

(1842-1917)

Co. D and Co. B, 2nd Rhode Island Infantry Regiment | Library of Congress

“July 3rd 1863–This morning the troops were under arms before light and ready for the great battle that we knew must be fought. The firing began, and our Brigade was hurried to the right of the line to reinforce it. While not in the front line yet we were constantly exposed to the fire of the Rebel Artillery, while bullets fell around us. We moved from point to point, wherever danger to be imminent until noon when we were ordered to report to the line held by Gen. Barney. Our Brigade marched down the road until we reached the house used by general Meade as Headquarters…. To our left was a hill on which we had many Batteries posted. Just as we reached Gen. Meade’s Headquarters, a shell burst over our heads, and it was immediately followed by a shower of iron. More than two hundred guns were belching forth their thunder, and most of the shells that came over the hill struck in the road on which our Brigade was moving. Solid shot would strike the large rocks and split them as if exploded by gun powder. The flying iron and pieces of stone struck men down in every direction. It is said that this fire continued for about two hours, but I have no idea of the time. We could not see the enemy, and we could only cover ourselves the best we could behind rocks and trees. About 30 men of our Brigade were killed or wounded by this fire. Soon the Rebel yell was heard, and we found since that the Rebel General Pickett made a charge with his Division and was repulsed after reaching some of our batteries. Our lines of infantry in front of us rose up and poured in a terrible fire. As we were only a few yards in rear of our lines we saw all the fight. The firing gradually died away, and but for an occasional shot all was still. But what a scene it was. Oh the dead and the dying on this bloody field. The 2nd R.I. lost only one man killed and five wounded … Again night came upon us and again we slept amid the dead and the dying.”

Robert Hunt Rhodes, ed., All for the Union: The Civil War Diary and Letters of Elisha Hunt Rhodes (New York: Orion Books, 1991). Copyright 1991 Robert Hunt Rhodes.

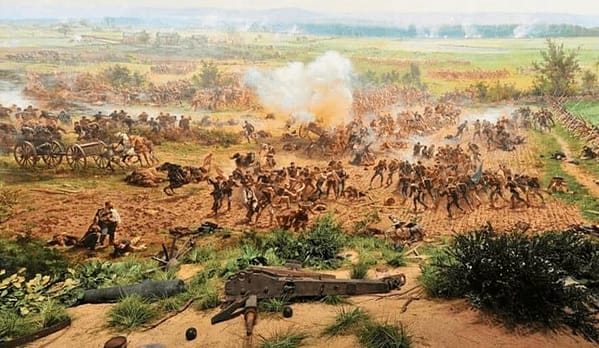

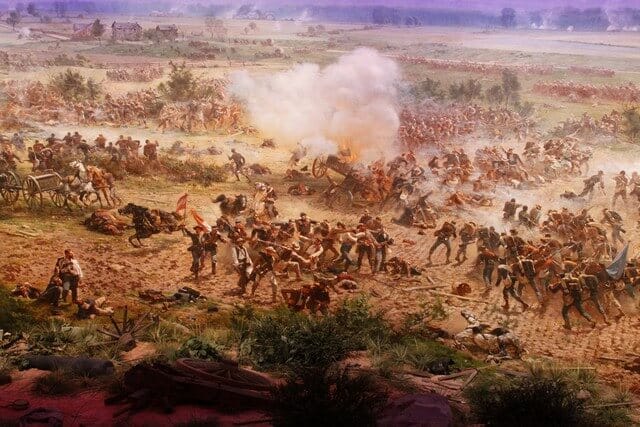

Then out of the woods came Lee’s assault column – known as Pickett’s Charge. Pickett, Pettigrew, and Trimble moved forward with their divisions of 15,000 troops. Three gray lines of Confederate infantrymen marched in silence at a brisk, steady pace toward Cemetery Ridge. Union artillery fire and musket volleys cut them down. The Union fighters positioned behind stone walls, piled fence rails, and breastworks, watching the slaughter of advancing Confederates.

(1884) Cyclorama Painting at Gettysburg Museum and Visitor Center

generalstannardhouse.org

Some Confederate units were separated from others while on their way to the Union center, and General George J. Stannard‘s Vermont Brigade took advantage of the opportunity. He maneuvered his brigade in drill-field fashion and moved between two Confederate columns. Turning one way, his brigade weakened the normal function of the flank of one column and then, turning his brigade around, fired into the flank of the other column.

(1817-1863)

Virginia Historical Society | ncpedia.org

The Confederates, led by General Lewis A. Armistead of North Carolina, managed to breach the Union line at a place called “the Angle.” General Hancock had command of the Angle, and he knew General Armistead before the war. General Armistead was immediately gunned down, and his dying wish was for his old friend, General Hancock, to send his personal effects back home. The rest of General Armistead’s men were either killed or captured, and the hole in the Union line was closed. Pickett’s supporting divisions gave way, and he was driven back with tremendous losses by General Hancock’s counterattack.

by Mark Maritato | maritato.com

At the same time that Pickett’s charge hit the Union center, a large cavalry battle developed three miles to the east, known as the East Cavalry Field. The 1st Michigan Calvary Volunteer Regiment, with approximately 2,000 troops under the command of 23-year old West Pointer, Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer, was dispatched to protect the Union Army flanks along the far right of the Union battle line and secure the road to town.

battlefields.org

General Lee ordered General J.E.B. Stuart’s Cavalry Division to ride east and position to the rear of the Army of the Potomac and isolate the Union lines from communication. Anxious to prove himself after his embarrassing breach of duty at the start of the Gettysburg battle with General Lee, General Stuart quickly set a course that morning to ride in a wide sweep around the Union’s rear flank with his cavalry division and strike the Union troops where least expected.

General Custer’s 1st Michigan Calvary was already positioned and ready for battle near Rummel’s barn. The area had an unusual stillness, except for the far off sound of guns and explosions of cannon fire to the west. Major Myron H. Beumont’s 1st New Jersey Cavalry also arrived at the Rummel farm to see what might be there, but General Custer received orders to mobilize his cavalry to a different sector. Union scouts rode in announcing they detected to the north a large turbulence of dust, likely from many troops and horses on the move. They knew the familiar sounds of low thunder from hundreds of horses’ hooves and the deep vibration in the earth from a slow, heavy rumbling of rolling artillery.

By early afternoon, Major General J.E.B. Stuart’s Cavalry Division made their way down into the valley from Cress Rridge – three miles east of Gettysburg, near Cress Run and Hanover Road. However, the Hampton’s Brigade and Fitzhugh Lee’s Brigade, at the rear of General Stuart’s line of march, unexpectedly lost the trail and came out into an open field at the north end of Rummel’s Woods. General Stuart soon learned of the mistake and attempted to bring them back into line to continue southward, while sending a unit of dismounted cavalrymen from Ferguson’s (Jenkin’s) Brigade to occupy the Rummel Barn in their front.

In response to the Confederate advance, Union General David M. Gregg had the men of Colonel John McIntosh’s Cavalry Brigade advance toward the Rummel Farm to join the 1st New Jersey Cavalry, who soon came under fierce fire and slowly driven back. Confederate cavalry was again on the advance.

Myron Holley Beaumont

(1837-1878)

Library of Congress

Albert G. Jenkins

(1830-1864)

civilwarprofiles.com

Wade Hampton III

(1818-1902)

essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com

Milton J. Ferguson

16th Virginia Cavalry Regiment

–replaced Brig.Gen.Jenkins–

civilwarcalvary.com

Fitzhugh Lee

(1835-1905)

Library of Congress

John Baillie McIntosh

(1829-1888)

Army of the Potomac,

Calvary Corps.

2nd Division, First Brigade

Library of Congress

Later that day, Major General Stuart directed his Generals Wade Hampton III and Fitzhugh Lee to lead their cavalry brigades, approximately 2,000 troops, in a charge against the Union lines to break their front position. General Hampton’s Calvary advanced slowly, at first, then picked up speed as they neared the targeted Union position. Union Artillery saw the Confederate cavalries advance and fired both single and double canisters into the Confederate troops. Hampton’s and Lee’s men tightened their ranks and continued riding at full speed toward the Union line. The only choice for the Union Calvary Commander, General David McMurtrie Gregg, was to order his cavalry troops to counterattack the Confederates.

(1833-1916)

battlefields.org

Brigadier General Custer also saw the advancing Confederate troops riding fast, straight for the Union position. He immediately sent word to the Union Commander, General D.M. Gregg, that he was taking his 1st Michigan Calvary Regiment straight into the advancing Confederates, even though they were vastly outnumbered. General Custer and his Calvary set out slow, then increased the horses’ pace to full speed as both armies drew closer then violently clashed into each other, savagely fighting with swords while fallen troops were in desperate hand-to-hand combat.

Custer’s Michigan Brigade against Hampton’s Cavalry

“The sound was like the falling of timber, so sudden and violent that many of the horses were turned end over end and crushed their riders beneath them. The clashing of sabers, the firing of pistols, the demands for surrender and the cries of the combatants now filled the air.“

Union Captain William E. Miller – Company H of the 3rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Cavalry | Gettysburg

Rummel Farm

Medal of Honor Recipient – 1897 gardnerlibrary.org

Brigadier General Custer and his 1st Michigan Calvary blocked the Confederates from advancing by boldly slashing their way through the Confederate troops. Brigadier General D.M. Gregg saw the 1st Michigan Calvary needed immediate help and he ordered McIntosh’s Brigade along with the units of the 3rd Pennsylvania to strike the Confederate right. The separated divisions of the 1st New Jersey, 5th, 6th, and 7th Michigan were reorganized and sent behind Colonel John McIntosh and the 3rd Pennsylvania to support the attack on the Confederate right. The violent engagement between both armies seemed utterly relentless. Then on the Confederate left flank, Captain Hampton S. Thomas, led another New Jersey unit into the fight.

Union Captain William E. Miller, who commanded Company H of the 3rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, was ordered to move his cavalry unit to the right into the woods, and remain there for further orders. As he did so, he watched the Confederate Cavalry move past him. He was torn between obedience to his commander’s order or disobedience, and he couldn’t stand by without taking action. He motioned to his horsemen to move out of the woods and directly into the flank of the Confederate column. Miller’s Calvary surprise attack on the Confederate’s flank caused them to fall back, helping to bring the Union Cavalry to victory. Captain Miller received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his quick action despite disobeying orders.

Gettysburg – 4 JULY 1863

The midsummer heat and humidity generated the usual afternoon thunderstorms and flash floods often resulted from the heavy rain, and so it was that afternoon, General Lee began the withdrawal of the Army of Northern Virginia from Gettysburg south toward the Potomac River. But General Lee found the river’s waters crested from the rain, blocking his evacuation to the next position west of Sharpsburg. Meanwhile, President Lincoln and General Henry W. Halleck urgently ordered General Meade to pursue the retreating Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and swiftly engage General Lee before the Potomac River subsided. General Meade responded by sending his cavalry to surround the Army of Northern Virginia and harass its retreat. They assaulted the Confederate Army’s wagon trains, while liberating Union prisoners and capturing wounded Confederates.

Ultimately, Meade abandoned the idea of direct pursuit and decided to cut off Lee’s army from its Potomac River crossings. Meade’s hesitation created other pauses in decisions to confront Lee’s retreating army, enabling Lee’s army to complete building defensive, earthwork fortifications and a pontoon bridge by July 13th, and they safely crossed the Potomac River to Virginia under the cover of night.

Edwin Forbes | Library of Congress

(1823-1895)

General Lee evacuated his wounded by a train of wagons and ambulances under the protection of Confederate Cavalry Brigadier General J.D. Imboden and a battery of horse artillery. General Imboden led the 17-mile long train on a route under heavy rain through Cashtown, then to Greencastle, Hagerstown, and Williamsport till he reached the river, where General Lee directed General Imboden to rest there and feed the animals. When rested, he was to proceed to Winchester where General Lee would communicate with him again.

“Shortly after noon of the 4th the very windows of heaven seemed to have opened. The rain fell in blinding sheets; the meadows were soon overflowed, and fences gave way before the raging streams. During the storm, wagons, ambulances, and artillery carriages by hundreds by thousands were assembling in the fields along the road from Gettysburg to Cashtown, in one confused and apparently inextricable mass. As the afternoon wore on there was no abatement in the storm. Canvas was no protection against its fury, and the wounded men lying upon the naked boards of the wagon bodies were drenched. Horses and mules were blinded and maddened by the wind and water, and became almost unmanageable. The deafening roar of the mingled sounds of heaven and earth all around us made it almost impossible to communicate orders, and equally difficult to execute them.’

Miller, J.A. (intro). The Retreat from Gettysburg; by Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden (C.S.A.), 1887 | emmitsburg.net

“After dark I set out from Cashtown to gain the head of the column during the night. My orders had been peremptory that there should be no halt for any cause whatever. If an accident should happen to any vehicle, it was immediately to be put out of the road and abandoned. The column moved rapidly, considering the rough roads and the darkness, and from almost every wagon for many miles issued heart rending wails of agony. For four hours I hurried forward on my way to the front, and in all that time I was never out of hearing of the groans and cries of the wounded and dying. Scarcely one in a hundred had received adequate surgical aid, owing to the demands on the hard working surgeons from still worse eases that had to be left behind. Many of the wounded in the wagons had been without food for thirty-six hours. Their torn and bloody clothing, matted and hardened, was rasping the tender, inflamed, and still oozing wounds. Very few of the wagons had even a layer of straw in them, and all were without springs. The road was rough and rocky from the heavy washings of the preceding day. The jolting was enough to have killed strong men, if long exposed to it. From nearly every wagon as the teams trotted on, urged by whip and shout, came such cries and shrieks as these: “Oh God! Why can’t I die? My God! Will no one have mercy and kill me Stop! Oh! For God’s sake, stop just for one minute; take me out and leave me to die on the roadside.” I am dying! I am dying! My poor wife, my dear children, what will become of you?’

“Some were simply moaning; some were praying and others uttering the most fearful oaths and execrations that despair and agony could wring from them; while a majority, with a stoicism sustained by sublime devotion to the cause they fought for; endured without complaint unspeakable tortures, and even spoke with cheer and confront to their unhappy comrades of less will or more acute nerves. Occasionally a wagon would be passed from which only low, deep moans could be heard.’

“No help could be rendered to any of the sufferers. No heed could be given to any of their appeals. Mercy and duty to the many forbade the loss of a moment in the vain effort then and there to comply with the prayers of the few. On! On! We must move on. The storm continued, and the darkness was appalling. There was no time even to fill a canteen with water for a dying man; for, except the drivers and the guards, all were wounded and utterly helpless in that vast procession of misery. During this one night I realized inure of the horrors of war than I had in all the two preceding years.”

Gettysburg – 5 JULY 1863

Daughters of Charity

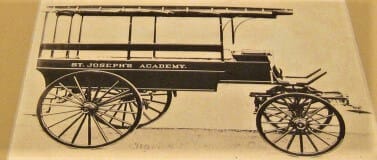

Reportedly, there were more than 230 Daughters of Charity who served as nurses in hospitals for the North and South during the Civil War providing medical care for all soldiers. The Daughters of Charity organization was founded in 1809 by St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, which included a convent, orphanage, and a school for Catholic girls – St. Joseph’s Academy. Their community was located in Emmitsburg, Maryland, just south of the Mason-Dixon line that separated Maryland from Pennsylvania.

In late June 1863, the Sisters were aware of Confederate and Union armies advancing north of Emmitsburg toward Gettysburg. On July 1st, the Daughters of Charity community heard a battle begin. There was endless gunfire and cannon blasts in the distance. The battle continued two more days. The sounds of weapons grew louder and unending. Then there was silence. Silence for a long time. The battle ended. On July 5th, Father Francis Burlando, Chaplain at the Daughters of Charity Emmitsburg community, took a group of nuns and traveled to Gettysburg to help medically care for wounded soldiers. In an omnibus cart, they slowly made their way to the town of Gettysburg where they quickly found themselves moving through the gory after-effects of hell on earth. Sisters of Charity soon became widely known as the “angels of the battlefield.”

docarchivesblog.org

“What a frightful spectacle met our gaze! Houses burnt, dead bodies of both Armies strewn here and there, an immense number of slain horses, thousands of bayonets, sabres [sic], wagons, wheels, projectiles of all dimensions, blankets, caps, clothing of every color covered the woods and fields. We were compelled to drive very cautiously to avoid passing over the dead. Our terrified horses drew back or darted forward reeling from one side to the other. The farther we advanced the more harrowing was the scene; we could not restrain our tears…The inhabitants were just emerging from the cellars to which they had fled for safety during the combat; terror was depicted on every countenance; all was confusion.”

Father Francis Burlando | Chaplain of the Daughters of Charity’s Emmitsburg community | 5 July 1863 | npsgnmp.wordpress.com

“Impossible to describe the condition of those poor wounded men. Generally the case where there is so much powder used, that they were covered with vermin … we could hardly bear this part of the filth.”

Sister Camilla O’Keefe – Daughters of Charity, Emmitsburg, Maryland | Gettysburg, 1863

Father Burlando quickly reviewed the hospital locations in town at the Gettysburg Hotel, then promptly assigned the Sisters to various hospital sites. One of the makeshift hospitals that the Daughters of Charity assisted as nurses was at St. Francis Xavier Roman Catholic Church on High Street. The hospital had a high volume of wounded and it was terribly understaffed. Many of the wounded were still there since the church was initially converted into a hospital on the first day of battle. The nuns worked around-the-clock caring for the wounded offering water, food, providing bandages and basic medical care. They comforted the wounded and dying through prayers, religious emblems, and requested baptisms, as well as helping with letters home to their families.

Emmitsburg was close in proximity to Gettysburg, approximately ten miles, and its short distance enabled the community of the Daughters of Charity to delegate additional Sisters as nurses to Gettysburg, along with delivering needed provisions such as food, water, and other supplies for the wounded. The Sisters were continually surrounded by unpleasant sights, sounds, and smells at every hospital they served, but never complained. They cleaned many wounds, and many were infested with maggots. They combed lice from the hair of the wounded but, unfortunately, these parasites often hid among their clothing and were unknowingly transported back to the Emmitsburg community.

An unusual and moving story experienced by the Daughters of Charity were from two Sisters, Veronica and Serena Klemkiewicz (biological sisters in real life), who served in Gettysburg as nurses on the battlefields. They and other Sisters were stationed in the bloodied battlefields searching for wounded and dying soldiers who needed care, as they laid among the unburied dead. One day, the two Sisters heard a wounded soldier on Culp’s Hill calling out for water and as they drew closer, they saw a soldier’s face covered in blood. They gently cleaned the blood from his face and were shocked to uncover a familiar face, their brother, Thaddeus. He was a private who belonged to the Confederate 1st Maryland Battalion (later known as the 2nd Maryland) and was badly wounded fighting the Union troops on Culp’s Hill. This was a most unexpected family reunion and not often experienced by others, but a thrilling and blessed opportunity to save their own brother from a lonely death on the battlefield. They nursed him back to health and he survived the Civil War.

***

The people of Gettysburg slowly re-appeared after the three-day war. All around them there were scenes of devastation. Their homes were broken and others in pieces; they were destroyed by shot and shell or transformed into hospitals filled with the wounded and sick. Their water wells were nearly empty, as well as their supplies. Thousands of horses and mules lay dead everywhere, including dead and wounded soldiers. Foul odors from decomposing flesh permeated throughout the hot summer air, sickening the remaining residents of Gettysburg. Burying thousands of human and animal remains was a monumental task, but they knew it must be done quickly to avoid disease and epidemics. So many of the dead soldiers were interred in shallow graves from where they fell in battle or in the fields of nearby hospitals, and they constructed crude wooden boards to identify the buried, marking their names in pencil.

Helpers came to search the fields for the wounded. Some were women who came for the dead – searching for lost loved ones. Some had come for souvenirs from the battle and in their search lost arms and legs, some lost their lives from active artillery shells that exploded. It took many months to bury the dead, clear debris, care for the injured, and give support and consolation for survivors.

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Eventually, the weather eroded the shallow graves and Gettysburg’s citizens called for proper burials of the Union dead and the need for a soldiers’ cemetery. Most of the Union dead were exhumed and moved to the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. The Confederate dead, however, remained where they were buried for eight years until they were finally moved to Southern cemeteries and reburied. With so many dead, historians estimated several hundred bodies were never found for exhumation and reburial and, thus, remain to this day in unmarked graves.

commentary

In 1964, I was old enough to understand what this national park represented: death and cruelty of war. It showed me people can be hateful, stubborn, and revengeful as well as willing to sacrifice everything for their beliefs. I knew even then at such a young age that human slavery was horrible and wrong, but what I did not understand was why people could not resolve their problems without having to kill each other. Why did these people want to go to war and fight their fellow neighbors, or even their own families, over a disagreement on differences?

And so I discovered through research that it was not only the attitude of slavery, but also the differences between economics, politics, Constitutional law, manners, customs, and morals that eventually divided the North and the South. Angry words, less and less reasoning, hatred toward one another, and violent reactions were warning signs of a coming disunity that was to tear the Union apart. Finally, the South chose to secede from the Union in order to justify the principle of states’ rights, and maintain their right to slavery as absolute and untouchable.

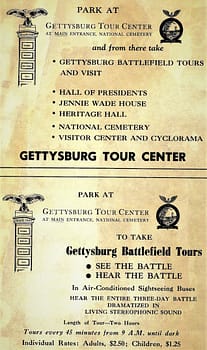

My visit to the Gettysburg Battlefield in 1964 – 101 years after the fact – was chiseled in my memory and remains with me to this day. I remembered how I felt driven to physically touch with my fingers field artifacts; cannons, a wagon, a stone wall, a picket fence, and battlefield cemetery headstones. I wanted to directly connect to its living history, and I envisioned myself there – hearing battle sounds, human shouts and cries, gun and cannon fire. I remembered overlooking the battlefields from Round Top, Little Round Top, Devil’s Den, Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge, and Seminary Ridge, and I imagined the battles there, the noise and smoke from artillery, as well as the screams of pain from the wounded and dying on those bloodied fields. I was horrified with thoughts of so many horses killed, the wounded having amputations, and those left in the fields to die in agony.

I stood in fields and hilltops that eerily haunted me as the Park’s tour guides retold their events. I was introduced to an old world of real people who were not just history book characters of names and places, but a lost world that was different from mine. I discovered they were people who lived in a culture with a morality that were more important and valuable to them than what I knew from my society in 2013. I wanted to somehow feel the fright and horror from those who fought this gruesome battle. And I most wanted to understand how someone’s convictions could propel them to kill friends and brothers. So I wrote this piece to commemorate the 150th Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg because my visit there meant so much to me.

References

- Ansley, C.F. (ed.). 1935. The Columbia Encyclopedia in One Volume. Compiled and edited at Columbia University

- Blog of Gettysburg National Military Park. 2019. The Daughters of Charity and the Battle of Gettysburg

npsgnmp.wordpress.com - Burns, Stanley B., MD. The Burns Archive

www.pbs.org/mercy-street/uncover-history/behind-lens/hospitals-civil-war/ - Casey, Sister Eleanor DC. 1996. The Daughters of Charity of Emmitsburg & the Battle of Gettysburg. Emmitsburg Area Historical Society

http://www.emmitsburg.net/archive_list/articles/history/civil_war/doc_civil_war.htm - Catton, B. 1965. The Centennial History of the Civil War. Volume Three. Never Call Retreat. E.B. Long, Director of Research

- Daughters of Charity Provincial Archive

https://docarchivesblog.org/category/civil-war/page/9/ - East Calvary Field and Battle of Gettysburg

- http://www.thomaslegion.net/eastcavalryfieldgettysburg.html

- Gettysburg National Military Park

nps.gov/parkhistory - Gettysburg Visitor’s Guide. 1964

- Holbrook, T. 2016. The Men of Action: Unsung Heroes of East Calvary Field. Gettysburg Seminar Papers.

npshistory.com - Miller, W. 1958. A New History of the United States

- Morris, R.B. (ed.). 1953. Encyclopedia of American History

- National Park Service. 1999. Choices and Commitments: The Soldiers at Gettysburg. Teaching with Historic Places; National Register of Historic Places, Washington, DC.

files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED436450.pdf - Skousen, W. Cleon. 1981. The 5000 Year Leap: The 28 Great Ideas That Changed the World. National Center for Constitutional Studies

- Ward, G.C., K. Burns, and R. Burns. 1990. The Civil War: An Illustrated History. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., NY. Distributed by Random House, Inc., NY

- Williams, B. 2007. Battle of Gettysburg. www.militaryhistoryonline.com

First published 2013; Updated August 2023