French Captain Joncaire told George Washington Ohio was theirs. They would take the Ohio since it was rightfully theirs, it was discovered by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle some 60 years ago. No more English settlements on the river or any of its waters.

FRENCH CAPTAIN CHABERT DE JONCAIRE

Captain Chabert de Joncaire (Philippe-Thomas) was called “Nitachinon” by the Iroquois, a trader, an officer in the colonial regular troops, Indian agent, and interpreter. By the age of ten, Philippe-Thomas Chabert de Joncaire was sent to live among the Senecas, near Geneva, New York – probably at Ganundasaga – where his father’s trading post was reported to have been located. He entered the colonial regular troops in 1726, became a second ensign in 1727, and rose to captain by 1751 – under a diplomat’s career, and not a soldier’s.

He succeeded his father (Louis Thomas de Joncaire Sieur de Chabert) in 1735 as principal agent for New France among the Iroquois – as hostage, trader, interpreter, and political agent. He supplied European trade goods that the Indians had become dependent, appeased the Iroquois when French or Indian allies made trouble, and appeased the French when young warriors were rebellious and combative. Hostility towards Indian nations who were unfriendly to the French had to be maintained. He also persuaded the Senecas to continue supplying Fort Niagara – near Youngstown, New York – with fresh game. By 1744, the British had offered a reward for Joncaire dead or alive.

In 1749, he became interpreter and adviser for Pierre-Joseph Céloron de Blainville’s expedition to the Ohio valley. When Céloron forces withdrew in the autumn of 1749, Joncaire joined them. He returned to the area in 1750 and was stationed at Logstown – now Ambridge, Pa. – with 12 soldiers to prepare for a much larger French occupation. He saw that all the Indians favored the traders from Pennsylvania and Virginia who ventured into the region, but he was determined to change the Indians favor toward the French. Joncaire used bribes, threats, and promises as he struggled to win them over. Thus, when Paul Marin de La Malgue arrived in 1753 to build a line of forts linking Lake Erie and the Ohio, many Delawares and Shawnees were impressed by the large French force. This may have pushed them to challenge Iroquois influence in the area. Joncaire then moved to Venango – Franklin, Pa. – until 1755, where he was in charge of the skillful diplomacy needed to maintain the friendship of the Delawares and Shawnees. He also needed to make Chief Half-King Tanaghrisson ineffective as spokesman for the Iroquois on the Ohio, since he opposed French construction of forts on Indian land in the Ohio.

French CAPTAIN CHABERT DE JONCAIRE

4 December 1753

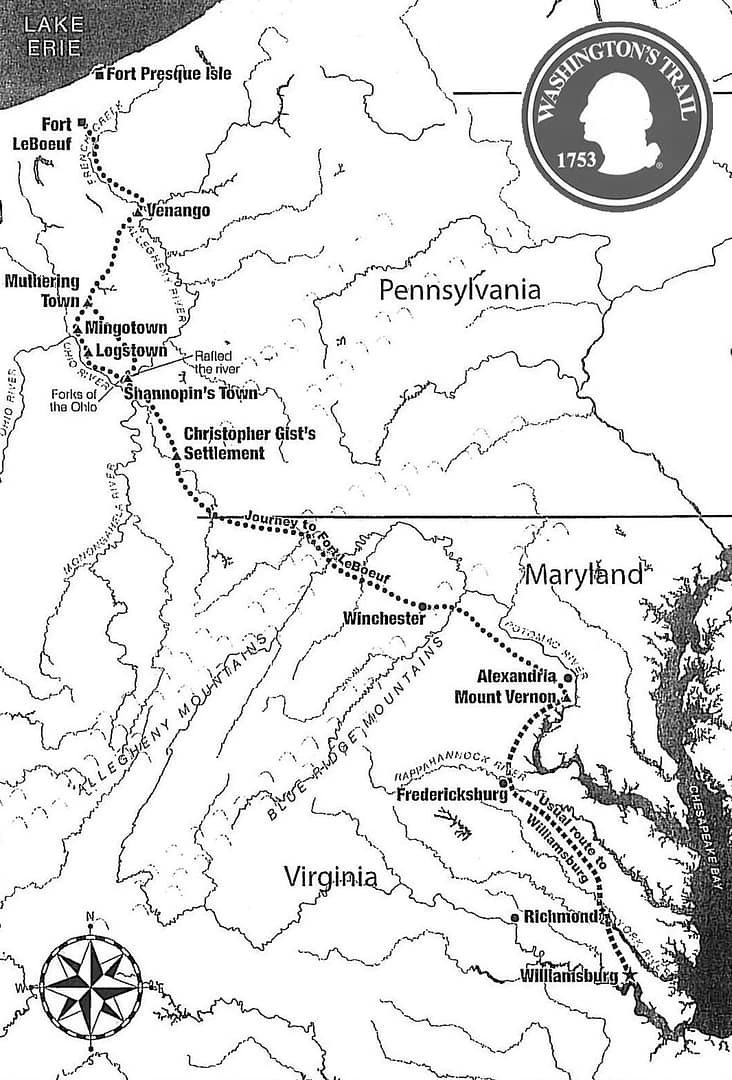

George Washington set out mid-morning with Tanaghrisson the Half-King,

White Thunder, Jeskakake, and Best Hunter, traveling

Over 70 miles to reach the old Indian town of Venango.

It was at the mouth of French Creek on the Ohio,

North 60 miles from Logstown, but they had to go

Farther, 70 miles, due to bad weather and snow.

Washington saw French colors raised from Frazier’s cabin

As he rode there to inquire from the French within

About Frazier, and the lost English traders from Venango.

Of three Officers there, it was Captain Chabert de Joncaire–

Who told Washington he had Command of Ohio, but there

Was a General Officer at a Fort nearby who would know.

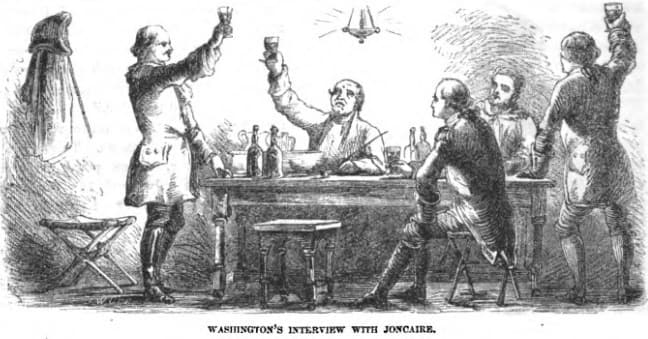

Joncaire invited Washington and his men to sup with them,

So gracious was he and obliging, offering wine to all the men-

Talk was no longer sober, drunken words were now their position.

Washington did not share the wine only ate the food,

He listened to loose French tongues turn the table mood

From polite pretension to direct claims of Ohio possession.

The French warned Washington they would take the Ohio,

It was rightfully theirs, discovered by La Salle some 60 years ago-

No more English settlements on the river or any of its waters.

The French knew the English could raise two men to their one,

And they knew the English were slow to move an army and overrun

The French secured in their position, so they were not deterred.

However, the death of their General recalled French soldiers

That left four Forts with small garrisons as their only defenders-

Washington learned much from Joncaire’s candid statements.

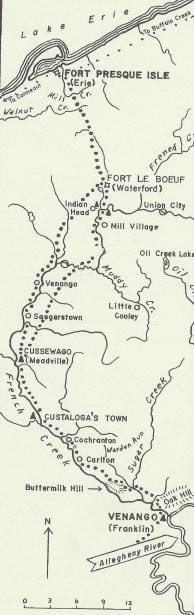

Four forts south of Lake Ontario – the first location

On French Creek, 60 miles from Venango, the second location

On Lake Erie, 15 miles from the first – a place for supply shipments.

The third location was 120 miles to the Falls of Lake Erie

Where all goods were stored from Montreal and, lastly,

Fourth location was 20 miles farther on Lake Ontario.

Three other forts were between fourth fort and Montreal-

The first at a distance of nearly 600 miles overall,

Directly across the lake from the English Fort Oswego.

Settled families moved away from France’s threat,

And the best intelligence Washington could get

Was information on 1500 men this side of Lake Ontario.

Advised of four weeks voyage if good weather, no more-

But not with canoes for they must stay close to shore,

Use of barks or large vessels was a better way to go.

5 December 1753

A hard rain continued through the day-

Preventing travel and causing much delay

For Washington and Half-King.

Promptly, Captain Joncaire expressed his concern

That as Commander, he was last to learn

Of Washington traveling with Chief Half-King.

Joncaire insisted, why didn’t Washington break free

At once, or does he disregard rules of civility

By not directly bringing Half-King to his attention?

Washington remained thoughtful and composed,

Then with a firmness of mind, he boldly disclosed

French company was a disagreeable provocation.

Washington explained he heard Joncaire say

Typical dispraises of Indians only yesterday,

And he felt such improper behavior displeasing.

Washington kept his other opinion silent

For detaining Half-King, as Joncaire was a monument

Of influence for Indians – he was always promising.

Washington watched the Indians with Captain Joncaire

As he expressed great pleasure seeing them all there,

But Washington knew Joncaire was a manipulator.

He gave trifling presents and poured liquor so fast

The Indians were soon unfit for any business task,

But they knew Joncaire as their loyal advocator.

6 December 1753

Tanaghrisson met Washington in his tent with a frown-

His Indian escorts were drunk and unsound,

Unable to do business with Captain Joncaire.

He also told Washington about a kindled Council Fire

Where business with the French would soon transpire,

Adding Joncaire was now Governor of all Indian Affairs.

Washington stayed since he wanted to know

Council news of Captain Joncaire – he chose to forego

His horses, sending them up French Creek to overnight.

They all met in Council where Chief Half-King presented

The French Speech-Belt to Joncaire, who rejected

Possession but, rather, sent it to Fort Commander first light.

7 December 1753

Washington tried but could not get an Indian escort

Enlisted for their journey to the next fort-

French ruses deterred Indians from going.

Washington had no choice but send surveyor Gist

To fetch the Indians and persuade them to assist,

Even though dark, gray clouds were growing.

Travel was bad, excessive rain and snow

Through mires and swamps, which they chose

As a better way than cross a rising creek.

Its water moved fast and rose quite high,

Impossible to wade or raft, or even try-

For such a crossing was very bleak.

From Venango they saw far-reaching land-

Of broad meadows that spanned

Four miles in length and wider in some places.

Washington arrived at Fort Le Boeuf four days later-

His men hungry and tired, with a greater

Need for dry clothes and warm fireplaces.

FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR | Part 3

Continued…

Updated 2020

References

The Journal of Major George Washington. 1754. Williamsburg printed. Reprinted in London for T. Jefferst, the Corner of Martins Lane. Mount Vernon, VA.

http://www.mountvernon.org/education/primary-sources-2/article/the-journal-of-major-george-washington/

Washington, George and Royster, Paul , editor, “The Journal of Major George Washington (1754)” (1754). Electronic Texts in American Studies. 33.

http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas/33