Then OTIS rose, and first in patriot fame,

To listening crowds resistance dared proclaim.

From soul to soul the great idea ran,

The fire of freedom flew from man to man,

His pen, like Sydney’s made the doctrines known;

His tongue like Tully’s shook a tyrant’s throne.

From men like OTIS Independence grew

From such beginnings empire rose to view.

Thomas Dawes – “On the Death of the Honourable James Otis, Esq.”

OTIS died from a lightning strike at the House of Mr. Isaac Osgood (26 May 1783)

The New-Hampshire Gazette and General Advertiser (7 June 1783)

- Post Contents -

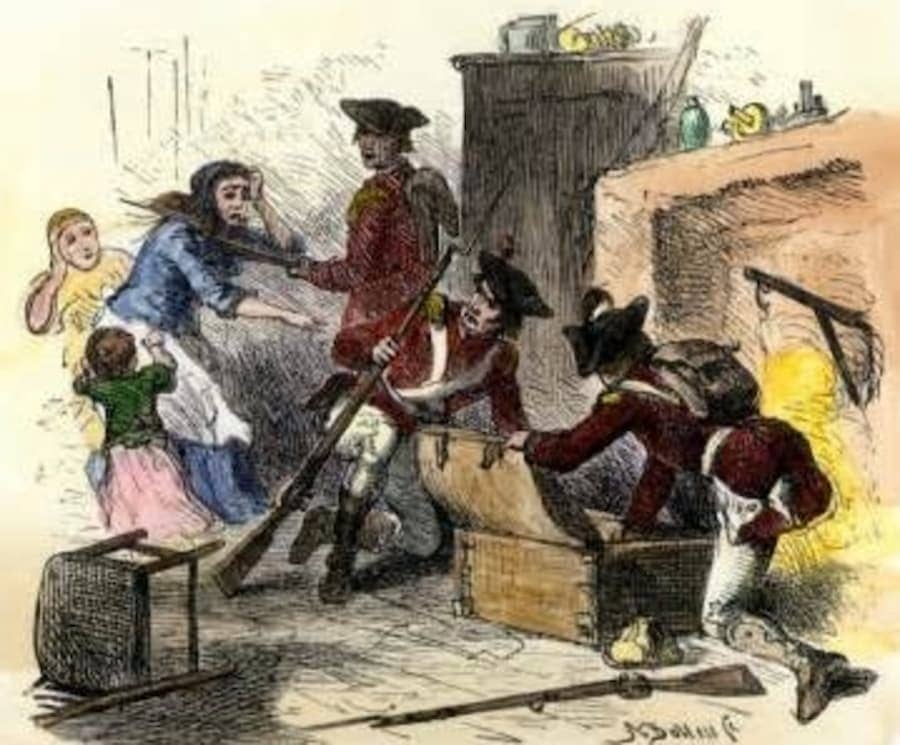

first illegal act by the british military, 1761

The first illegal act by the British military was in 1761, which ordered the courts of New England to issue warrants called, ‘Writs of Assistance’. These writs authorized customs officers to search for smuggled contraband within suspected properties because of Boston’s prime location for bootlegger business amid its busy seaports. Boston’s constables and/or public officers willfully aided the British in these searches and seizures within the private dwellings and warehouses. Any man’s house could be entered, their property searched, and their possessions seized on the slightest suspicion of smuggling. These wrongful actions were carried out without ‘due process of law’ and without a jury trial.

“…to take a Constable, Headborough or other publick Officer inhabiting near unto the place and in the daytime to enter and go into any House, Shop, Cellar, Warehouse, or Room or other place and incase of resistance to break open doors, chests, trunks, and other package there to seize and from thence to bring any kind of goods or merchandize whatsoever prohibited and uncustomed and to put and secure the same in our Storehouse in the port next to the place where such seizure shall be made.”

-M.H. Smith, Writs of Assistance Case, 559

England’s trade laws were enforced under the authority of the Court of Exchequer, which produced and released England’s writs of assistance; however, America had no Court of Exchequer and its violations of commercial law went to trial either through a court of common law or in the Vice-Admiralty Courts and, the English, wanted the vice-admiralty courts because it had the advantage of being independent of colonial authority. Thus, the judges, not the juries, in these courts made the decisions on the case and their wages were paid from the Crown and not from colonial lawmakers. Accordingly, should a customs agent charge a local merchant or shipowner of an illegal action, the customs agent would not need to worry about the possibility of losing his allotment of the fine because of a sympathetic local jury. Whereas, the Vice-Admiralty Court would uphold the trade laws ensuring the Crown’s revenue as well as the custom agent’s allotment.

***

The earliest relevant statute, an Act of Parliament passed in 1660, authorized the issuance ‘to any person or persons’ of a warrant to enter any house to search for specific goods, upon oath made of their illegal entry before “the lord treasurer, or any of the barons of the Exchequer, or chief magistrate of the port or place where the offense shall be committed, or the place next adjoining thereto” (12 Car. 2, c. 19, §1 [1660] — Lawrence A. Harper: The English Navigation Laws, N.Y. [1939]; 388-390, 395-404; Bernard Knollenberg, Origin of the American Revolution, 1759-1766, N.Y. [1960]; 169-171).

The warrant so issued enabled the holder “with the assistance of a sheriff, justice of peace or constable, to enter into any house in the day-time where such goods are suspected to be concealed, and in case of resistance to break open such houses, and to seize and secure the same goods so concealed; and all officers and ministers of Justice are hereby required to be aiding and assisting thereunto” (Ibid.)

However, the statute central to the 1761 controversy was the Act of 1662. In the organization of a customs administration for the British Isles, this ‘Writ of Assistance’ was first used to define a customs search warrant. This act provided “any person or persons, authorized by writ of assistance under the seal of his majesty’s court of exchequer, may enter any premises in the day time, with a constable or other officer, using force if necessary, and there seize any contraband goods found” (13 & 14 Car. 2, c.11 §5[2] [1662]).

british acts of trade

The British Acts of Trade were a parcel of legislation enacted in 1660. Throughout the Revolution, it regulated the course of colonial trade and the levying of tariffs during its various phases. In the end, it became a rigid system of enforcement but, initially, it intended to offer opportunities for the English merchant and shipbuilder to erect monopolies in the colonial trade. However, some influential colonial shipbuilders and merchants also took advantage of the moneymaking benefits from the system and used the assurances it offered for the available trade markets. Ultimately, the system used unethical methods to make profits for the Crown; all goods that moved through the English ports were subjected to duties to be paid there by the importer or exporter (T.C. Barrow, Colonial Customs Service 26-32, 283-286).

To enforce the Acts of Trade ordinances in the colonies, customs officials were authorized by and held accountable to England’s Commissioners of the Customs (Plantation Duties Act, 25 Car. 2, c. 7, §3 [1673]). These colonial officers managed a difficult, document control system that needed to insure full compliance with both regulatory and revenue stipulations. The base of the system required all vessels arriving from or departing to faraway destinations be cleared for travel with the customs officers at each port (15 Car. 2, c. 7, §8 [1663]; 13 & 14 Car. 2, c. 11, §§2, 3 [1662]; made compatible in colonies by 7 & 8 Will. 3, c.22, §6 [1696]). This policy allowed a continual inspection with each vessel’s compliance with the Acts by requiring certified documents; i.e., vessel and crew nationality were restrained by the ship’s register, and the certified copy of the master’s or owner’s oath stating the vessel was English built, owned, and manned (Plantation Certificate, certificate of registry-7 & 8 Will. 3, c. 22, §§17-21 [1696]).

A vessel that transported an inventory of goods was requisitioned to provide a bond upon clearing that they would only port their ship at an English or colonial harbor, and if a certificate of compliance was not returned at the specified time, the bond would be forfeited (12 Car. 2, c. 18, §19 [1660]; 7 & 8 Will. 3, c. 22, §13 [1696]). Thus, to ensure that European goods were shipped from England, the master was mandated to tender a manifest that showed the type, quantity, and origin of his cargo before his ship entered port and unloaded. Duty payments were then handled through the manifest and the certificates of the officers upon entry and clearance, whereby the duties were then officially rendered (15 Car. 2, c. 7, §8 [1663]; 13 & 14 Car. 2, c. 11, §§2, 3 [1662], made compatible in the colonies by 7 & 8 Will. 3, c. 22, §6 [1696]; Instructions by the Commissioners for Managing and Causing to be levied and collected His Majesty’s Customs, Subsidies, and other Duties in England to Who is Established Collector of His Majesty’s Customs in America [London], ca. 1733).

In order to prevent violations, customs officers used their unconditional authority to search vessels and premises ashore for suspected contraband, including its seizure (13 & 14 Car. 2, c.11 §§4-11. 15-20, 32-34 [1662]-applicable in the colonies by 7 & 8 Will. 3 c. 22, §6 [1696]). Violators were accountable to an assortment of penalties – from small fines for failure to comply with specific laws to the forfeiture of a vessel and its goods for an an illegal action involving violations against the requirements of the Acts. Although such infringements in Britain were inside the limits of the Court of Exchequer, in the colonies, however, many would have been sued in the Courts of Vice Admiralty – which were established in 1697 exclusively for this purpose. The customs officers were permitted to bring charges for penalties and forfeitures, then solicit a lawsuit against the offender. The customs officers would then collect their share of the proceeds upon conviction. Authority over such actions were coexistent with common law, but, in Massachusetts these officers chose to remain in the protection of the Admiralty where a court outcome and recovery would not depend on a jury’s partiality to the offender (Barrow, Colonial Customs Service, 124-127, 145-150; Wroth, “The Massachusetts Vice Admiralty Court,” in George A. Billias, ed., Law and Authority in Colonial America).

In its beginning, there was some opposition to this system but, sometime after 1725, the colonist commotion against the system eventually calmed. Two reasons may have influenced the colonists’ to semi-accept the inevitability of the system: one was the trade benefits they received from England as compensation for the disadvantages the regulations imposed; and the second was that, after 1725, English policy appeared to be purposefully disregarding the violations of the system. Collecting revenue from the colonies was in small amounts because of prevalent negligence with enforcing revenue measures, which was well known and excused by Parliament. It was also suspected that a comparable negligence spread throughout the enforcement for other Act stipulations. (Harper Navigation Laws, 365-378; Dickerson, Navigation Acts, 208; Barrow, Colonial Customs 1-17, 512-524).

During the French and Indian War ([1754-1763] or Seven Years War), the New England colonies traded massively with the enemy which distressed the Crown into forcing a clampdown on the unrestrained shipping activities by way of their Acts of Trade. Immediately, outrage came from the Boston merchants against the Admiralty Court and customs officials, including their opposition against the customs application for Writs of Assistance.

As Parliament ended its neglect of its Acts of Trade policy and its lax enforcement, John Adams entered the scene and became involved with the Crown’s return to its strict policy of enforcement. Adams was present for the first of two disputes that was held before the Superior Court at Boston in February 1761. Though he was not appointed legal counsel, he did provide a significant report that was publicly distributed. And though Boston’s rejection of the application for Writs of Assistance was unsuccessful, it was a first alarm for resistance against the Acts of Trade that would climax in the American Revolution.

the writs case of 1761

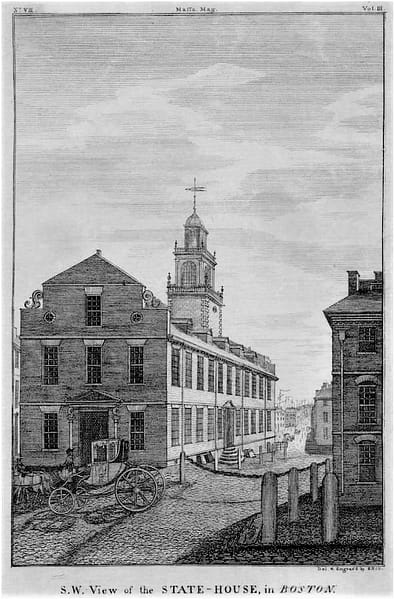

The Writs of Assistance was being improperly used to enforce the century-old Acts of Trade in order to prevent the irrepressible smuggling in Massachusetts. However, James Otis, Jr. was, by then, Advocate-General of the Vice-Admiralty Court when the legality of these warrants were rebuked. He was called upon to defend its legality by the Vice-Admiralty Court, but Otis promptly resigned in protest. Soon after, a group of Boston merchants sought to retain him as their counsel to dispute the writs in the Superior Court of Massachusetts at the Old State House (originally the site of the Old Town House in Boston). They offered Otis payment for his legal service, but he refused. He opted to support their cause voluntarily.

His legacy is the Writs Case -and- the importance of the Fourth Amendment

Since the death of King George II in 1760, new Writs of Assistance were requisitioned by the British to replace the expired writs of King George’s reign, but Boston’s merchants opposed the new proposed writs. They also disputed England’s unreasonable and, at times, irrational granting of writ search warrants without the legal obligation required to observe the regular legal order. They dogged the British government to function in accordance with law, and to promise to follow the fair procedures which the merchants were entitled; i.e., ‘due process’.

This Writs Case marked James Otis as the first to challenge British search and seizure methods, by detailing a comparable concept for administering suitable laws for search and seizure. Otis’s “…proclamation that only specific writs were legal was the first recorded declaration of the central idea to the specific warrant clause.” (William J. Cuddihy, The Fourth Amendment: Origins and Original Meaning 382 [2009].) His concept was so specific on search and seizure requirements that they were later incorporated into the Fourth Amendment.

“Otis’s importance, then and now, stems not from the particulars of his argument; instead, he played, and should continue to play, an inspirational role for those seeking to find the proper accommodation between individual security and governmental needs.“

T.K. Clancy, The Importance of James Otis; Mississippi Law Journal-Vol. 82:2 at 488

Arguments presented by James Otis before the Superior Court, 24 February 1761, on the Writs of Assistance grants to royal customs officials were recorded in history as one of the earliest statements of a direct challenge from colonists against English Parliamentary regulation. The event was held in the Council Chamber at the Old State House in Boston. The building housed the Massachusetts House of Representatives and the Governor’s Council.

There were two hearings on the proposed writs – February 1761 and re-argued in November 1761. At the first hearing, the foremost issue was whether the Superior Court should continue to grant the writs in general and open-ended form, i.e., general warrants, or should it limit the writs to a single occasion based on circumstantial information provided under oath (QUINCY, supra note 13; MLJ at 493). After the first hearing, the court requested information from England concerning the proper practice of writs. The court learned that England used general writs and it was “…judged sufficient to warrant the like practice in the province” (T. HUTCHINSON, The History of the Province of Massachusetts Bay [1749 to 1774] 95 [1828]; supra note 9; MLJ at 489).

2nd President of the United States (1797-1801)

It was a very cold afternoon on the 24 February 1761 and inside Boston’s Old Town House, friends Samuel Quincy and John Adams sat together in the Chambers. Adams described the scene in a letter to William Tudor some 60 years later:

“…near the Fire were seated five Judges, with Lieutenant-Governor Hutchinson at their head, as Chief Justice, all arrayed in their new, fresh, rich robes of scarlet English broadcloth; in their large cambric bands, and immense judicial Wiggs. In this Chamber were seated at a long table all the Barristers of Boston and its neighbouring County of Middlesex in their Gowns, Bands, and Tye Wiggs. They were not seated on ivory Chairs, but their dress was more solemn and more pompous than that of the Roman Senate, when the Gauls broke in upon them. …Two portraits, at more than full length, of King Charles the Second and of King James the Second, in splendid golden frames, were hung up on the most conspicuous sides of the apartment. If my young eyes or old memory have not deceived me, these were as fine pictures as I ever saw.”

John Adams Papers, Legal Papers of John Adams, Vol. 2, Cases 31-62; Adams to Tudor, 29 March 1817, Works of John Adams 10::244-45

The Old Town House was crammed with Boston’s political upper crust. They occupied every seat and every standing space, while a crowd waited outdoors in the cold for bits of news. They all came to witness what was rumored to be sensational entertainment between a successful and highly-respected lawyer throughout New England as well as a master of argument, James Otis, Jr., confronting his old law teacher and mentor, high Mason and Whig, Jeremiah Gridley, who is now his opposition in court and defender of the Crown. With him on the bench were four associates: Benjamin Lynde, John Cushing, Chambers Russell, and Peter Oliver. This case was expected to be the biggest legal battle in Massachusetts since the notorious Salem Witch Trials of 1692.

by John Smibert Harvard, 1731

Another challenge for James Otis was with the Chief Justice presiding over the case, Thomas Hutchinson. He was a personal adversary with Otis and their rivalry was a popular subject in town gossip and private speculation. Fortunately for Otis, most Boston colonists already favored him and were very distrustful and critical of Hutchinson because of his public endorsement of the Writs and concurrent political service on several high-ranking positions in government – Chief Justice, Lieutenant Governor, Governor’s Council member, and Judge of Probate.

(1711-1780)

by Edward Truman (1741)

Hutchinson’s summary of the Writs of Assistance Case:

“It was objected to the writs, that they were of the nature of general warrants’ that, although formerly it was the practice to issue general warrants to search for stolen goods, yet for many years, this practice had been altered, and special warrants only were issued by justices of the peace, to search in places set forth in the warrants; that it was equally reasonable to alter these writs, to which there would be no objection, if the place where the search was to be made should be specifically mentioned, and information given upon oath. The form of a writ of assistance was, it is true, to be found in some registers, which was general, but it was affirmed, without proof, that the late practice in England was otherwise, and that such writs issued upon special information only.”

Michael Dalton, The Country Justice 418 (1746) – John Adams retained a copy of this treatise in his library [see John Adams Library] – Thomas Hutchinson, The History of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, from 1749 to 1774; at 93-94 (London, 1828); at 89, 93-94

Jeremiah Gridley was first to present his case for the Crown and he began the argument supporting the request for new writs on part of the customs service in Massachusetts Bay. His position was simple: “…without such writs of assistance the customs officials could not properly exercise their office” (Joseph Hawley – Common-place Book; Manuscript Division, NY Public Library). The use of such writs, he contended, was provided for by acts of Parliament. In Great Britain, they were issued by the Court of Exchequer and in Massachusetts by the Superior Court of Judicature. Gridley then referred to specific statutes that dated back to Charles II and William III to further substantiate his argument ([12th & 14th of Charles II] Statutes at Large [ed. G. Eyre and A. Strahan, London, 1786]). He based the legality of this practice in the province on William III (7 & 8 Wm 3, c. 22, §6) and by the statute of the 6th of Anne, which reached the higher courts of the colonies and their authority to issue such writs.

Gridley pointed out there were ample legal precedents for the writ in question. “What this Writ of assistance is,” he said, “we can know only by Books of Precedents. And We have produced, in a Book intituld the modern Practice of the Court of Exchequer, a form of such a Writ of assistance to the officers of the Customs” (Wroth and Zobel, Legal Papers of John Adams 2:136-138).

Gridley then turned his argument toward the need for revenue officers to retain their existing powers to summon officers to carry out ‘like assistance’ which was standard in England. And without revenue, a nation could not protect itself or maintain itself. “Tis the necessity of the Case and the benefit of the Revenue that justifies this Writ, and the necessity of having public taxes effectually and speedily collected is of infinitely greater moment to the whole than the Liberty of any Individual” (Wroth and Zobel, Legal Papers of John Adams 2:136-138).

Otis’s legal assistant, Oxenbridge Thacher, was another distinguished attorney who also represented the Boston merchants. He joined Gridley on the floor and opened his rebuttal on the Writs of Assistance by firmly refuting Gridley’s point: “…he [Gridley] found no such writ in the ancient books.” Thacher continued, “…the most material question … whether the practice of the Exchequer was good ground for this Court … for in England all information of uncustomed or prohibited goods were in the Exchequer; so the Custom-House officers were the officers of the court, under the eye and discretion of the Barons, and so accountable for any wanton exercise of power.” As for the writ, once granted, was not returnable. The difference “…in England they seized [goods] at their peril, even with probable cause.” (Thacher’s argument reproduced by Horace Gray from Adams’ notes and carefully edited [L.H. Gipson] – Quincy Reports, p.46-71.)

(1719-1765)

Thacher introduced doubt on the existence of a former case for the writ and argued that the powers given by the Act of Parliament were too extensive to be used under a general warrant. The majority of Thacher’s argument that Adams recorded was pointed to the control by the Superior Court that officiated as the Court of Exchequer. This rule was formerly rejected in a prior case, but the Massachusetts court lacked the authority the Exchequer had in order to control the English customs officers. Thacher concluded that there was a clear difference between English and provincial courts in the power and practice of overseeing customs officers who might abuse writs. Such unchecked power controlled by customs officers was dangerous, and colonial customs officials were not required to ‘return’ to court and account for their use of the writs.

Thacher then withdrew from the floor and James Otis stood to address the court. He began by justifying his involvement in the case then to his objections with the writs of assistance – such as his observance of assaults against British liberties and his obligation to oppose any instrument of corruption, slavery, and arbitrary power like the writ of assistance.

“Otis was a flame of Fire! With promptitude of Clasical Allusions, a depth of Research, a rapid Summary of Historical Events and dates, a profusion of legal Authorities, a prophetic glare [i.e. glance?] of his eyes into futurity, and a rapid Torrent of impetuous Eloquence, he hurried away all before him, American Independence was then and there born. The seeds of Patriots and Heroes to defend the Non sine Diis animosus infans, to defend the vigorous Youth, were then and there sown. Every man of an [immense] crowded Audience appeared to me to go away, as I did, ready to take up Arms against Writts of Assistances. Then and there was the first scene of the first Act of Opposition to the arbitrary Claims of Great Britain. Then and there the Child Independence was born. In fifteen years, i.e. in 1776, he grew up to manhood, declared himself free.”

John Adams to William Tudor, 29 March 1817. Letterbook copy, Adams Papers, John Adams in a contemporaneous report of the proceedings in Congress on the Declaration of Independence, referred to “the Argument concerning Writs of Assistance, in the Superior Court, which I have hitherto considered as the Commencement of the Controversy, between Great Britain and America.” John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776, Adams Family Correspondence, 28

Otis brought forth a variety of arguments against the writs as being unfounded, including the ability of courts to question acts of Parliament (Petition of Lechmere, Editorial Note, in 2 Legal Papers of John Adams, supra note 86, at 106). His arguments on the limits of judicial and legislative authority became a significant point, which offered an alternate vision for proper standards of warrants to issue. He also argued that courts had the power to find illegal those warrants that did not meet that criterion. Otis condemned the general writ of assistance as a violation of American liberties; however, the critical point was that he directed a constitutional attack against the legislation authorizing the writ.

Otis then turned his attention to a relevant question regarding the proper standard for regulating searches and seizures:

I will admit that writs of one kind may be legal; that is, special writs, directed to special officers, and to search certain houses, &c. specially set forth in the writ, may be granted by the Court of Exchequer at home, upon oath made before the Lord Treasurer by the Person who asks it, that he suspects such goods to be concealed in those very places he desires to search. …And in this light the writ appears like a warrant from a Justice of the Peace to search for stolen goods. Your Honors will find in the old books concerning the office of a Justice of the Peace, precedents of general warrants to search suspected houses. But in more modern books you will find only special warrants to search such and such houses specially named, in which the complainant has before sworn that he suspects his goods are concealed; and you will find it adjudged that special warrants only are legal. In the same manner I rely on it, that the writ prayed for in this petition, being general, is illegal. It is a power that places the liberty of every man in the hands of every petty officer. I say I admit that special writs of assistance, to search special places, may be granted to certain persons on oath; but I deny that the writ now prayed for can be granted, for I beg leave to make some observation of the writ itself. …In the first place, the writ is universal, being directed ‘to all and singular Justices, Sheriffs, Constables, and all other officers and subjects’; so, that, in short, it is directed to every subject in the King’s dominions. Every one with this writ may be a tyrant; if this commission be legal, a tyrant in a legal manner also may control, or murder any one within the realm. In the next place, it is perpetual; there is no return. A man is accountable to no person for his doings. Every man may reign secure in his petty tyranny, and spread terror and desolation around him. In the third place, a person with this writ, in the daytime, may enter all houses, shops, &c. at will, and command all to assist him. Fourthly, by this writ not only deputies, &c., but even their menial servants, are allowed to lord it over us. Now one of the most essential branches of English liberty is the freedom of one’s house. A man’s house is his castle; and whilst he is quiet, he is as well guarded as a prince in his castle. This writ, if it should be declared legal, would totally annihilate this privilege. Custom-house officers may enter our houses, when they please; we are commanded to permit their entry. Their menial servants may enter, may break locks, bars, and every thing in their way; and whether they break through with malice or revenge, no man, no court, can inquire. Bare suspicion without oath is sufficient. This wanton exercise of this power is not a chimerical suggestion of a heated brain. I will mention some facts. Mr. Pew had one of these writs, and when Mr. Ware succeeded him, he endorsed this writ over to Mr. Ware; so that these writs are negotiable from one officer to another; and so your Honors have no opportunity of judging the persons to whom this vast power is delegated. Another instance is this: Mr. Justice Walley had called this same Mr. Ware before him, by a constable, to answer for a breach of Sabbath-day acts, or that of profane swearing. As soon as he had finished, Mr. Ware asked him if he was done. He replied, Yes. Well then, said Mr. Ware, I will show you a little of my power. I command you to permit me to search your house for uncustomed goods. And went on to search his house from the garret to the cellar; and then served the constable in the same manner. But to show another absurdity in this writ; if it should be established, I insist upon it, every person by the 14 Charles II has this power as well as custom-house officers. The words are, ‘It shall be lawful for any person or persons authorized’, &c. What a scene does this open! Every man, prompted by revenge, ill-humor, or wantonness, to inspect the inside of his neighbor’s house, may get a writ of assistance. Others will ask it from self-defence; one arbitrary exertion will provoke another, until society be involved in tumult and in blood.’

“Again, these writs are not returned. Writs in their nature are temporary things. When the purposes for which they are issued are answered, they exist no more; but these live forever; no one can be called to account. Thus reason and the constitution are both against this writ … [Otis thereafter examined the legal authority for the writs, arguing that there was none.] But these prove no more than what I before observed, that special writs may be granted ‘on oath and probable suspicion’. The act of 7 & 8 William III that the officers of the plantations shall have the same powers, &c. is confined to this sense; that an officer should show probable ground; should take his oath of it; should do this before a magistrate; and that such magistrate, if he think proper, should issue a special warrant to a constable to search the places.”

The Works of John Adams, supra note 7, app. a, at 524-25 (1850)

Otis elaborated on the high level of protection the common law afforded the house under the “castle” doctrine, and, thus, established that the common-law authorities already condemned general warrants as illegal. Considering those suppositions, Otis concluded that any statute that authorized use of a general writ would be so opposite to the principles of law as to be “void.” Otis did not argue for an undefined concept of “reasonableness” but, instead, articulated specific standards to measure the propriety of the writs; requirements that regulated the issuance of a common law search warrant for stolen goods and to also determine whether an intrusion was justified.

Otis concluded his argument by underscoring why general writs were dangerous to liberty and, accordingly, unconstitutional. It was a broad-minded legal theory that called for judicial annulment of parliamentary law. Otis stated, “An act against the constitution is void” – and that one statement echoed throughout the annals of American legal argument. Otis continued by saying the Court had to interpret the questioned statutes in relationship to the constitutional principles that safeguarded the liberties of the subject. The Court was then forced to reject applications for general writs of assistance, because the constitution only permits that “special writs may be granted on oath and probable suspicion” and existing statutes “can prove no more.”

The Court delayed its decision on the legality of writs of assistance after the February hearing. Chief Justice Thomas Hutchinson explained, “The court was convinced that a writ, or warrant, to be issued only in cases where special information was given upon oath, would rarely, if ever, be applied for, as no informer would expose himself to the rage of the people.” Requiring writs of assistance to be supported by an oath on special evidence for each customs search would effectively end meaningful enforcement of the trade laws and collection of revenue. And some of Hutchinson’s fellow judges doubted “whether such writs were still in use in England…and, if judgement had been then given…” Hutchinson noted, “it is uncertain on which side it would have been.” In order to clear up the legality of general writs, Hutchinson acted on “the first opportunity in his power to obtain information of the practice in England.” As a result, the Massachusetts court suspended its judgment until such clarification was received (Hutchinson, History of the Province 3:68).

closure

The question that challenged the court was the nature of the warrants actually used in England. Judgment was suspended pending an inquiry by Hutchinson into the Exchequer practice. The reply was that general writs were granted freely upon application of the Commissioners of Customs to the clerk of the Exchequer (Hutchinson, Massachusetts Bay, ed. Mayo, 68; Quincy, Reports [Appendix] 414-416; Freiberg, Prelude to Purgatory 15 note), but the whole matter was reargued in Boston, November 1761, at an adjournment of the August term. After the second hearing, the court decided unanimously in favor of the writ (Quincy Reports, 51-57; Boston Gazette, 23 Nov. 1761, reprinted in Quincy Reports [Appendix] 416-434).

by Edward Truman (1734) masshist.org

The decision seemed not to have been an order allowing the release of a writ to a specific officer, but a type of declaratory judgment of a court that the writ might thereafter be issued upon due application according to English practice. Thus, after the argument, the first writ granted was given to Charles Paxton on 2 December 1761, on behalf of the Surveyor General’s application. A similar procedure was followed for each writ issued afterward in Massachusetts (see application [1762-1769] in SF 1005150, printed in Quincy, Reports [Appendix] 416-434).

The efforts of Otis and Thacher did not change the view of the established rules of the law. Writs were permitted for release and the practice was continued. Moreover, in 1767, Parliament revised the laws to effect the issuance of writs of assistance in all the colonies; a concern not with a constitutional general warrant, or a court power to deal with an unconstitutional Act, or even the practice in the Exchequer, but an assurance to the high courts of judicature in the colonies that could exercise Exchequer powers (The Townsend Act, 7 Geo. 3, c. 46, §10 [1767], provided that, doubts having arisen about the legality of the use of writs of assistance in the colonies through the failure of the Act of 7 & 8 Will. 3, c. 22 to authorize any particular court to issue them).

In the 1761 argument, the theory of parliamentary sovereignty was understood in the Crown’s position (Gridley’s arguments, Nov 1761; Quincy, Reports 56-57). However, Otis pressed that acts of Parliament “against the Constitution” and “against natural Equity” were void, and that “the executive courts must pass such Acts into disuse.” Adams’s notes showed that Otis supported this position and cited the well-known language of Wenman Coke’s opinion in Bonham’s Case: “When an Act of Parliament is against Common Right and Reason, or repugnant, or impossible to be performed, the Common Law will controll it, and adjudge such Act to be Void.” (Bonham’s Case, 8 Co. Rep. 113b, 118a, 77 Eng. Rep. 646,652 — Otis’s citation of the case and the other phrases quoted here: Adams’s Minutes of the Argument: Suffolk Superior Court, Boston, 24 February 1761 [Adams Papers]; page-ref: ADMS-05-02-02-pb-0127).

If the argument of 1761 did not lead to great ends, it did mark for Otis a first opportunity to prepare and express ideas that were later circulated in his pamphlets throughout the colonies. And when John Adams commented sixty years later, “Then and there the child of Independence was born,” he actually meant the suggestion that Parliament’s power was not absolute but it started the intellectual process which led him to the forefront of the revolutionary movement, then surely the argument of 1761 was a vital predecessor of those of 1776 (JA’s comment of 3 July 1776: in a contemporaneous report of the proceedings in Congress on the Declaration of Independence, referred to “the Argument concerning Writs of Assistance, in the Superiour Court, which I have hitherto considered as the Commencement of the Controversy, between Great Britain and America.” (J Adams to Abigail A, 3 July 1776, 2 Adams Family Correspondence 28).

***

From a statement by Daniel Webster in 1826:

“Otis’s speech against the Writs of Assistance in Boston, 1761, was a masterly performance exhibiting a learned, penetrating, convincing, constitutional argument expressed in a strain of high and resolute principles.”

Daniel Webster, “Adams and Jefferson,” Works of Daniel Webster, Vol. 1 (Boston: Little & Brown, 1851, 121

George Bancroft summarized Otis’s performance by saying it was:

“…the opening scene of American Resistance.”

George Bancroft, History of the United States, from the the Discovery of the American Continent, Vol. 4 (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1856), 414

John Fiske described Otis’s speech:

“…there appeared in the horizon the little cloud like unto a man’s hand which came before the storm. This was the famous argument on the writs of assistance.”

John Fiske, Thomas Hutchinson, Last Royal Governor of Massachusetts, in Essays Historical and Literary, Vol. 1 (New York: Macmillan, 1902), 26. Fiske paraphrases 1 Kings 18:44 — comparing Otis to the prophet Elijah.

John Clark Ridpath remarked on Otis’s speech:

“…the living voice which called to resistance, first Boston, then Massachusetts, then New England and then the World! …the greatest and most effective oration delivered in the American colonies before the Revolution.”

John Clark Ridpath, James Otis, the Pre-Revolutionist (Milwaukee: H.G. Campbell, 1903), 57-58, 47

Henry Lawrence Gipson said Otis’s legal argument:

“…helped to lay the foundation for the breach between Great Britain and her continental colonies.”

Lawrence Henry Gipson, The Coming of the Revolution, 1763-1775 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1954), 39

A.J. Langguth also commented on Otis’s dramatic speech and the Writs of Assistance trial:

“James Otis stood up to speak, and something profound changed in America.”

A.J. Langguth, Patriots: The Men Who Started the American Revolution (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988), 22.

***

Comment

I gained a better understanding of the importance to the opposition of British policy in 1761 from this examination of Otis’s Writs of Assistance trial. Surprisingly, the reliability of John Adams’s recollections of the case assured me of Otis’s deserved respect for his contribution to the patriot cause. All I can do is imagine Otis’s speeches were resounding to Boston’s colonists who knew that independence needed to be defended, and Otis’s performance proved he was a skilled orator, a master of argument, a defender of freedom, and a man who seeded the theory for an American Revolution. And both Otis and Adams knew the legal principle in the Writs case was central to the protection of liberties from the encroaching power of government.

It’s imperative that every American citizen should consider the seriousness and value of James Otis’s Writs of Assistance address and John Adams’s statement, “Then and there the Child of Independence was born.”

***

References

Adams, D. (2020). Essay: The Mad Patriot. American Studies Journal.

Adams Papers. Legal Papers of John Adams; Vol 2. N. Admiralty–Revenue Jurisdiction; Petition of Lechmere: Argument on Writs of Assistance, (1761).

Billias, George A., ed., Law and Authority in Colonial America; Barre, Massachusetts, in press. The Adams Papers; National Archives and Records Administration through the NHPRC.

Barrow, Thomas C. (1961). The Colonial Customs Service, 1660-1775. Harvard Univ. doctoral dissertation; 26-32, 283-286.

Clancy, Thomas K. (2012). The Importance of James Otis. Mississippi Law Journal; Vol. 82:2.

Clancy, Thomas K. (2011). The Framers’ Intent: John Adams, His Era, and the Fourth Amendment, Indiana Law Journal: Vo. 86, No. 3; Article 6.

Colonial Society of Massachusetts. Appendix VII [883-884]: Composition of the Superior Court of Judicature, 1745-1775

Dickerson, Oliver M. (1951). The Navigation Acts and The American Revolution, Philadelphia, PA.

Farrell, James M. (2014). The Child Independence is Born: James Otis and Writs of Assistance; in Rhetoric, Independence and Nationhood, ed. Stephen E. Lucas, Vol. 2: A Rhetorical History of the United States: Significant Moments in American Public Discourse, ed. Martin J. Medhurst (Michigan State University Press, forthcoming).

Gipson, Lawrence H. (1957). Aspects of the Beginning of the American Revolution in Massachusetts Bay, 1760-1762. American Antiquarian Society.

Harper, Lawrence A. (1941). The English Navigation Laws. A Seventeenth-Century Experiment in Social Engineering. New York: Columbia University Press. 1939. 503 pp. (25s) [365-378].

Massachusetts Historical Society. The Adams Papers; National Archives and Records Administration through the NHPRC

Massachusetts Historical Society. The Adams Papers; National Archives and Records Administration through the NHPRC — Arguments of James Otis before the Superior Court.

Massachusetts Historical Society. Adams Family Papers.

Massachusetts Historical Society. Legal Papers of John Adams; Vol 2.; Court of Vice Admiralty.

Putney, Clifford. (2004). Oxenbridge Thacher: Boston Lawyer, Early Patriot. Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 32, No. 1; Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University.

Reynolds, William L. (1998). Courts of Admiralty in Colonial America: the Maryland Experience, 1634-1776, by David R. Owen & Michael C. Tolley, 22 Md. J. Int’l. L. 407.

Stoebuck, William B. (1968). Reception of English Common Law in the American Colonies; Vol. 10, No. 2; Wm & Mary L. Review 393.

United States Courts of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit — Case: 19-30635; 6-7; U.S. Warrants — Fourth Amendment

Wroth, K.L. (1962). The Massachusetts Vice Admiralty Court and the Federal Admiralty Jurisdiction. American Journal of Legal History; Vol. 6, No. 4 — 347-348.