“They landed their prisoners, tied them, and butchered them. Some were cooked. They also cut their feet and hands off, and leave them weltering in their blood till they were dead.” Chief Pontiac.

As danger escalated around the garrison of Detroit, Britain’s commander-in-chief at New York ignored Detroit’s impending distress…

- Post Contents -

cuyler’s detachment – fate of the forest garrisons, 1763

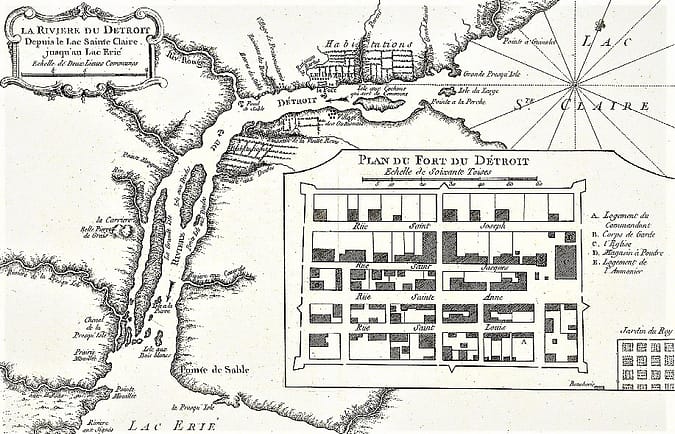

An uncommon quiet spread along the borders and neighboring forts until the opening of spring, when a strong detachment was sent up the lakes with a supply of provisions and ammunition for Detroit and other western posts. A convoy of boats pursued a course along the northern shore of Lake Erie as Gladwin’s garrison waited for their arrival with much anxiety as each day passed. The steady vigilance of the Indians never decreased. And for the soldier, there was grief if he showed his head above the palisades or exposed himself in front of a loophole.

Pontiac was so strongly committed to his fantasy of expecting French military assistance that he sent messengers to M. de Neyon, Major Commandant of the Illinois country. He earnestly petitioned a force of regular troops to be sent to his aid. Meanwhile, Gladwin ordered one of Detroit’s vessels to Niagara to hasten the convoy shipment of supplies. The next day, the schooner lay still at the entrance to Lake Erie when a multitude of canoes suddenly came out of hiding from nearby shores. In the prow of the first canoe, the Indians used their prisoner, Captain Campbell, as a safeguard between themselves and the gunfire from the English. But Captain Campbell bravely called out to the English schooner to freely do their duty without regard to his welfare. Then, quite unexpectedly, a strong breeze arose flapping the sails that were stretched to the wind and the schooner quickly sailed onward in its course towards Niagara, leaving the Indian flotilla far behind (Penn. Gaz. No. 1807. MS. Letter – Wilkins to Amherst, June 18).

The fort, or rather town, of Detroit had by this time lost its customary liveliness. Its narrow streets were dark and quiet, with the exception of occasional characters like the Canadian rambling through the streets in a red cap and tawdry sash; the young sentinel, weary from walking to and fro in front of the commandant’s quarters; the officer hastily moving through the streets to an important appointment or may be a meal, and the Indian girl, probably some soldier’s or trader’s mate, who silently walked along in her finery of beads and vermilion.

However, the town opened to a very different scene on the morning of May 30th, 1763. At nine o’clock, a young sentinel shouted from the southeast bastion. Loud yelling from the direction of the river awakened Detroit from its apathy. Immediately, the fort was on alert and ready. Soldiers, traders, and residents hurried through the fort’s water gate to the canoe wharf and the narrow beach. The half-wild coureurs de bois, the young and muscular provincials, and the uniformed British soldiers all stood together in a crowd with badly worn, soiled clothes and haggard faces. They were dogged in their watch for the enemy.

Independent French Canadian trader

by Arthur Heming

The long expected convoy finally came into full sight. The faces on the shore were animated in joy. Along the farther side of the river, some distance below the fort, a line of boats was rounding the woody point – then called Montreal Point – with oars flashing in the sun. The red flag of England flew from the stern of the foremost (Pontiac, MS.). The garrison was relieved, their toils and dangers were drawing to an end. They shouted repeatedly three hearty cheers to their approaching friends, while a cannon from the bastion sent its loud boom of defiance to the enemy. When suddenly, every man’s face grew pale with horror as they watched dark, naked figures stand up in the boats with their wild war-whoops that fell faintly, and sadly upon their ears. The convoy was in enemy hands. All the boats were taken, and the troops from the detachment were either slain or made captive. The fort’s officers and men stood gazing in mournful silence.

In each of the boats, which there were eighteen, two or more of the captured soldiers were deprived of their weapons and were forced to act as rowers. They were guarded by several armed Indians, while many other Indians followed the boats along the shore for security (Pontiac, MS.). On the front boat, there were four soldiers and only three Indians. The larger of the two vessels lay anchored in the stream, close enough for a bow-shot from the fort, while the other vessel had gone down to Niagara to hasten re-enforcements. As the front boat came opposite to the anchored vessel, the steersman soldier conceived a daring plan of escape. The soldier called in English to his comrade to seize the Indian that sat in front of the boat and throw him overboard, but the soldier replied he wasn’t strong enough to do it. The steersman firmly directed the weakened soldier to change places with him and act as though he’s too fatigued to continue rowing. This movement would not raise suspicions with their Indian guard.

The bold soldier stepped forward as if to take his companion’s oar, when he abruptly seized the Indian by the hair, gripped with his other hand the Indian’s girdle at his waist and, with brute strength, lifted him high enough to throw him into the river. The boat rocked hard enough for the river water to surge over her gunwale. But the Indian clung to the bold soldier’s clothes and as he came up from the water, he trailed alongside the boat and stabbed the bold soldier repeatedly with his knife until the Indian dragged him overboard. Both men were carried by the swift current, rising and sinking, perishing in each other’s arms (Gouin, as a witness, affirmed the Indian freed himself from the dying grasp of the soldier and swam ashore).

The two remaining Indians jumped from the boat. The prisoners turned their boat and rowed for the distant vessel, shouting for aid. The Indians on shore opened a heavy fire upon them, while many Indian canoes paddled swiftly in pursuit. The men rowed in desperation because a horrible fate awaited them. Bullets from the Indians whizzed loudly around their heads and a soldier was soon wounded. The Indians’ lightweight birch canoes were rapidly gaining on them and escape seemed hopeless, when the sound of a cannon burst was heard and its ball flew past the soldiers’ boat. The cannon ball beat the water in a line of foam, narrowly missing the Indians’ front canoe. The Indians fell back disappointed, while the Indians on shore were scrambling for cover among the bushes to avoid another cannon ball strike. The prisoners soon reached the safe boat where they were greeted as if they were snatched from the jaws of death. “A living moment,” wrote an officer of the garrison, “that fortune favors the brave” (Penn. Gaz. No. 1807. St. Aubin’s Account; MS. Peltier’s Account, MS.).

Lieutenant Abraham Cuyler of the Queen’s Rangers

Lieutenant Abraham Cuyler of the Queen’s Rangers left Fort Niagara about the 13th of May for Fort Schlosser, located just above the falls, with 96 men and an ample supply of provisions and ammunition. For many days, he moved across the northern shore of Lake Erie without seeing friend or foe among the lonely forests and waters, until the 24th of May, when he landed at Point Pelée which was not far from the mouth of the River Detroit.

The men pulled the boats on the beach and prepared to make camp. A man and a boy went to collect firewood a short distance from the camp, when an Indian jumped out of the woods, grabbed the boy’ hair and tomahawked him. The man ran back to the camp shouting an alarm. Lieutenant Cuyler quickly gathered his soldiers into a semicircle in front of the boats. Then the Indians opened fire. There was a hot blaze of musketry from both sides. The Indians rushed from the woods in a large group and attacked the center of Cuyler’s line, which fell apart in every direction. Cuyler’s men were throwing down their guns and fleeing in a disorderly panic to the boats. Five were set afloat and crowded with terrified soldiers as they were pushed from shore. Cuyler found himself deserted by his men so he waded to his neck in the lake and climbed aboard one of the retreating boats. The Indians, meanwhile, pushed two more boats afloat and pursued the fugitives. Three boats, filled with soldiers, surrendered to the Indians but the last two boats, one in which Cuyler was on, made their escape.

Being abandoned by my men, I was forced to retreat in the best manner I could. I was left with 6 men on the beech, endeavoring to get off a boat, which not being able to effect, was obliged to run up to my neck, in the lake, to get to a boat that had pushed off, without my knowledge. – When I was in the lake I saw five boats manned, and the Indians have manned two boats, pursued and brought back three of the five, keeping a continual fire from off the shore, and from the two boats that followed us, about a mile on the lake; the wind springing up fair, I and the other remaining boat hoisted sail and escaped.

Cuyler’s Report, MS.

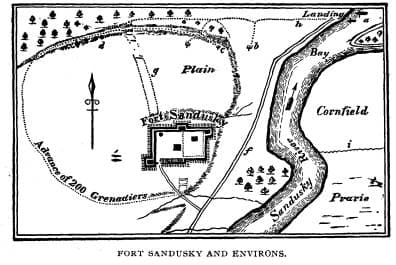

They rowed all night. Then they finally landed in the morning on a small island. Between 30 to 40 men, some wounded, were crowded into these two boats. The rest, about 60, were killed or taken. Cuyler decided to move for Sandusky, which, upon his arrival, he found burned to the ground. He immediately left and rowed along the south shore to Fort Presqú Isle, where he then proceeded to Niagara and reported his loss to Major Wilkins, the commanding officer (Cuyler’s Report, MS.).

Niagara, 6th June, 1763

“Just as I was sending off my Letter of Yesterday, Lieutenant Cuyler, of the Queen’s Rangers, arrived from his Intended Voyage to the Detroit. He has been very Unfortunate, having been Defeated by Indians within 30 miles of the Detroit River; I observed that he was Wounded and Weak, and Desired him to take the Surgeon’s Assistance and some Rest, and Recollect the Particulars of the Affair, and let me have them in Writing, as perhaps I should find it Necessary to Transmit them to Your Excellency, which I have now Done.

“It is probable Your Excellency will have heard of what has Happened by way of Fort Pitt, as Ensign Christie, Commanding at Presqú Isle, writes me he has sent an Express to Acquaint the Commanding Officer at that Place, of Sanduskie’s being Destroyed, and of Lieut. Cuyler’s Defeat.

“Some Indians of the Six Nations are now with me. They seem very Civil; The Interpreter has just told them I was writing to Your Excellency for Rum, and they are very glad.”

Extract from a MS. Letter – Major Wilkins to Sir J Amherst

The Wyandots were the predators that executed the ambush against Cuyler’s men. For days they concealed themselves about the mouth of the River Detroit, intercepting trading boats and parties of troops. Then, unexpectedly, Lieutenant Cuyler and his men landed their boats on the beach and the Wyandots were so excited to be so close to the enemy that the Indians lost their usual caution and rushed Cuyler and his men.

After the beach battle, the Indians returned back to shore from the pursuit of the boats and examined the supplies left behind by Cuyler’s detachment. It was a valuable prize. Ammunition, provisions, and numerous helpful objects, but, the one item the Indians favored was the large quantity of whiskey. The Indians immediately grabbed the liquor and took what they could carry to their respective camps. And throughout the night, there was loud partying and savage riots.

They poured the liquor into birch-bark containers, or anything else that worked as a waterproof cup, and drank the raw whiskey as if it was water. Some gathered in groups while others sat apart, some wailed and moaned in soppy drunkenness, and others were crazed like savage wild animals. Dormant jealousies awakened and old, forgotten arguments were revived. If not for the foresight of the squaws to take precautions in hiding the weapons before the drinking, there would have been much blood spilled. As it was, there were many Indians wounded, two died in the morning, and several others had their noses bitten off – a mode of revenge among the Indians in the upper lakes region that was popular during similar occasions.

The English, on the other hand, were angry but pleased over the drunken parties and savage riots. By late evening, two intoxicated Indians ran directly toward Fort Detroit shouting and boasting of their heroism, but were greeted with two rifle bullets that forced their bodies into the air as they fell dead.

The next day, after dusk had settled into night, several Canadians arrived at the fort. They brought awful stories of the scenes that occurred at the Indian camp. The soldiers gathered around the Canadians to hear their versions of what happened to the unfortunate soldiers taken prisoners. The listeners became unmovable from shock. None could help thinking how actually weak and fragile the fort’s barrier was in protecting them from a similar fate. They were told of rumors about naked corpses that were gashed with knives and scorched with fire as they floated along the Detroit waters. Fish were seen rising to the surface and nibbling at the clotted blood that clung to their gruesome faces.

The Indians, fearing that the other barges might escape as the first had done, changed their plan of going to the camp. They landed their prisoners, tied them, and conducted them by land to the Ottawas village, and then crossed them to Pontiac’s camp, where they were all butchered. As soon as the canoes reached the shore, the barbarians landed their prisoners, one after the other, on the beach. They made them strip themselves, and then sent arrows into different parts of their bodies. These unfortunate men wished sometimes to throw themselves on the ground to avoid the arrows; but they were beaten with sticks and forced to stand up until they fell dead; after which those who had not fired fell upon their bodies, cut them in pieces, cooked, and ate them. On others they exercised different modes of torment by cutting their flesh with flints, and piercing them with lances. They would then cut their feet and hands off, and leave them weltering in their blood till they were dead. Others were fastened to stakes, and children employed in burning them with a slow fire. No kind of torment was left untried by these Indians. Some of the bodies were left on shore; others were thrown into the river. Even the women assisted their husbands in torturing their victims. They slitted them with their knives, and mangled them in various ways. There were, however, a few whose lives were saved, being adopted to serve as slaves.

Pontiac, MS.

The remaining barges proceeded up the river, and crossed to the house of Mr. Meloche, where Pontiac and his Ottawas were encamped. The barges were landed, and, the women having arranged themselves in two rows, with clubs and sticks, the prisoners were taken out, one by one, and told to run the gauntlet to Pontiac’s lodge. Of sixty-six persons who were brought to the shore, sixty-four ran the gauntlet, and were all killed. One of the remaining two, who had had his thigh broken in the firing from the shore, and who was tied to his seat and compelled to row, had become by this time so much exhausted that he could not help himself. He was thrown out of the boat and killed with clubs. The other, when directed to run for the lodge, suddenly fell upon his knees in the water, and having dipped his hand in the water, he made the sign of the cross on his forehead and breast, and darted out in the stream. An expert swimmer from the Indians followed him, and, having overtaken him, seized him by the hair, and crying out, ‘You seem to love water; you shall have enough of it,’ he stabbed the poor fellow, who sunk to rise no more.

Gouin’s Account, MS.

Chief Pontiac Captures Fort Sandusky

It was late afternoon, not long after the killing of the two drunken Indians, when the garrison was greeted again with a dismal cry of death. A line of naked warriors were seen coming from the woods like a wall, rising up from the pastures to the rear of the fort. Each Indian was painted black and each wore a scalp fluttering from the end of a pole. The message was clear. A new disaster happened. Before nightfall, La Brosse, a Canadian, arrived at the gate with tidings that Fort Sandusky was taken and all its garrison slain or now captive (Pontiac, MS.).

Fort Sandusky was attacked by the band of Wyandots living in its neighborhood and aided by the Indians from Detroit. Among the few survivors of the slaughter was the commanding officer, Ensign Paully, who was brought prisoner to Detroit, bound hand and foot, and cheered along the way with the expectation of being burnt alive. Upon landing near the camp of Pontiac, he was surrounded by a crowd of Indians, mainly squaws and children who pelted him with stones, sticks, and gravel. He was forced to dance and sing, though he was definitely not lively. Then a kindly older woman, whose husband recently died, came forward and offered to adopt him in place of her deceased warrior husband. With no alternative other than the burning stake, Paully accepted the woman’s offer. He was first plunged into the river so the white blood might be washed from his veins, and then he was led to the lodge of the widow where he was treated with all the consideration due to an Ottawa warrior.

It wasn’t long before Major Gladwin received a letter from Ensign Paully, through a Canadian resident, which gave a full account of Fort Sandusky’s capture. It was the 15th of May when Paully was notified that seven Indians were waiting at the gate to speak with him. Paully knew very well several of the Indians and, without hesitation, he permitted the Indians to enter. Once in the commandant’s quarters, two of the treacherous Indians seated themselves on each side of Paully, while the rest were arranged in various parts of the room. The pipes were lit and the conversation began when an Indian, who stood in the doorway, abruptly made a signal by raising his head. Paully was immediately besieged and disarmed. At the same moment, there rose loud shrieks and yells, gunfire, and sounds of feet scurrying about the fort. Then it was quiet. Paully was led by his captors from his quarters to the parade ground which was strewed with the dead bodies of his murdered garrison. Come nightfall, Paully was led to the margin of the lake where several birch canoes lay in readiness. In the midst of darkness, the Indian party pushed out from shore and the captive saw the fort bursting in sheets of flames from all sides (MS. Official Document – Report of the Loss of the Posts in the Indian Country, enclosed in a letter from Major Gladwin to Sir Jeffrey Amherst, July 8, 1763).

Soon after the news of the loss of Fort Sandusky, Major Gladwin’s garrison heard the unfavorable reports that the strength of their enemy had been reinforced by two tough bands of Ojibwas. Pontiac’s forces within the district of Detroit numbered approximately 820 warriors, according to the local Canadians. Of these, 250 were Ottawas, commanded by Pontiac; 150 Pottawattamies, under Ninvay; 50 Wyandots, under Takee; 200 Ojibwas, under Wasson as well as another 170 of the same tribe, under their chief, Sekahos (Pontiac, MS.). The warriors brought their squaws and children along, giving the whole number of congregated Indians around Detroit to 3,000.

Chief Pontiac Captures St. Joseph Fort

The sleepless garrison at Fort Detroit were continually harassed by petty attacks, which wore them down with fatigue and feeling unwell. Yet more sad news of another disaster. On the 15th of June, numerous Pottawattamies were seen approaching the gate of Fort Detroit bringing with them four English prisoners who proved to be Ensign Schlosser, latest commander at St. Joseph’s Fort, and three private soldiers. The Indians wanted to exchange the English soldiers for several of their own tribe, who were prisoners at the fort for nearly two months. After a few hours, the Indians were granted their request. It was then that the garrison learned of the savage fate of their comrades at St. Joseph Fort.

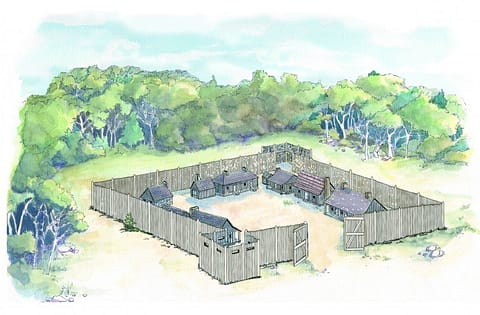

St. Joseph Fort / Artist rendition

This outpost stood at the mouth of the River St. Joseph’s near the head of Lake Michigan, a spot that has long been the site of a Roman Catholic mission. Among the forests, swamps, and ocean-like waters, and faraway from any shelter of a civilized man, the Jesuits had labored more than 50 years for the spiritual souls of the Pottawattamies who lived there in great numbers near the margin of the lake. According to Father Marest, as early as 1712 the mission was thriving. Around the mission a there was a little colony of forest-loving Canadians. It was here, too, that the French government established a military post whose garrison was eventually replaced by Ensign Schlosser with his command of merely 14 men. Come early morning on the 25th of May, and no suspicion of danger was suspected, an officer was informed that a large party of Pottawattamies from Detroit arrived to visit their relatives at St. Joseph’s Fort.

A chief named Washashe went to the commandant’s quarters with three or four followers requesting to hold a friendly ‘talk’. At the same moment, a Canadian rushed in with intelligence for Schlosser that the fort was surrounded by hostile Indians with clear intentions for violence. Schlosser immediately ran out of the apartment and crossed the parade that was crowded with Indians and Canadians, and he hastily entered the barracks. It was also crowded with hostile Indians – uncivil and unruly. Schlosser quickly called his sergeant to get the men under arms and he hurried back to the parade to muster a roll call and gather the Canadians together for action. Suddenly, Schlosser heard a wild cry from within the barracks. Then all the Indians in the fort rushed to the gate, tomahawked the sentinel and opened the gate wide as a free passage for their savage comrades. In less than two minutes, the fort was plundered, 11 men were killed. Three survivors, along with Schlosser, were bound and made prisoners. They were taken to Fort Detroit for a prisoner exchange (Loss of the Posts in the Indian Country, MS.; see also Diary of the Siege, p.25).

The following is from a letter, dated 19 June 1763, by Richard Winston, a trader at St. Joseph’s to his fellow-traders at Detroit:

“Gentlemen, I address myself to you all, not knowing who is alive or who is dead. I have only to inform you that by the blessing of God and the help of M. Louison Chevalie, I escaped being killed when the unfortunate garrison was massacred, Mr. Hambough and me being hid in the house of the said Chevalie for 4 days and nights. Mr. Hambough is brought by the Savages to the Illinois, likewise Mr. Chim. Unfortunate me remains here Captive with the Savages. I must say that I met with no bad usage; however, I would that I was (with) some Christian or other. I am quite naked, & Mr. Castacrow, who is indebted to Mr. Cole, would not give me one inch to save me from death.”

Fort Michilimackinac and Fort Ouatanon Captured

Not long after the St. Joseph’s news reached Detroit, Father Jonois, a Jesuit priest of the Ottawa mission near Michilimackinac, went to Pontiac’s camp with the son of Minavavana, the great chief of the Ojibwas as well as with several other Indians. The following morning, Father Jonois appeared at the fort’s gate and he carried with him a letter from Captain Etherington, commandant at Michilimackinac.

Michillimackinac, 12 June, 1763.

Sir:

Notwithstanding what I wrote you in my last, that all the savages were arrived, and that every thing seemed in perfect tranquillity, yet on the second instant the Chippeways, who live in a plain near this fort, assembled to play ball, as they had done almost every day since their arrival. They played from morning till noon; then, throwing their ball close to the gate, and observing Lieutenant Lesley and me a few paces out of it, they came behind us, seized and carried us into the woods.

In the mean time, the rest rushed into the fort, where they found their squaws, whom they had previously planted there, with their hatchets hid under their blankets, which they took, and in an instant killed Lieutenant Jamet, and fifteen rank and file, and a trader named Tracy. They wounded two, and took the rest of the garrison prisoners, five of whom they have since killed.

They made prisoners of all the English traders, and robbed them of every thing they had; but they offered no violence to the persons or property of any of the Frenchmen.

Captain Etherington spoke highly of Father Jonois’ character and conduct, and requested Major Gladwin to send all the troops he could spare up to Lake Huron since there is reason to believe that this post may be recaptured from the Indians. Gladwin was unable to help his brother officer’s request, he was hardly able to defend Fort Detroit. The Jesuit returned to his canoe and voyaged back to Michilimackinac.

Ouatanon, June 1st, 1763.

Sir:

I have heard of your situation, which gives me great Pain; indeed, we are not in much better, for this morning the Indians sent for me, to speak to me, and Immediately bound me, when I got to their Cabbin, and I soon found some of my Soldiers in the same Condition: They told me Detroit, Miamis, and all them Posts were cut off, and that it was a Folly to make any Resistance, therefore desired me to make the few Soldiers, that were in the Fort, surrender, otherwise they would put us all to Death, in case one man was killed. They were to have fell on us and killed us all, last night, but Mr. Maisongville and Lorain gave them wampum not to kill us, & when they told the Interpreter that we were all to be killed, & he knowing the condition of the Fort, beg’d of them to make us prisoners. They have put us into French houses, & both Indians and French use us very well: All these Nations say they are very sorry, but that they were obliged to do it by the Other Nations. The Belt did not Arrive here ’till last night about Eight o’Clock. Mr. Lorain can inform you of all. Just now Received the News of St. Joseph’s being taken, Eleven men killed and three taken Prisoners with the Officer: I have nothing more to say, but that I sincerely wish you a speedy succour, and that we may be able to Revenge ourselves on those that Deserve it.

I Remain, with my Sincerest wishes for your safety,

Your most humble servant,

Edwd Jenkins.N.B. We expect to set off in a day or two for the Illinois.

This expectation was not fulfilled and Jenkins remained at Ouatanon. A letter written to Gladwin on the 29th of July, he complained that the Canadians were secretly advising the Indians to murder all the English in the West.

News arrived about the loss of Ouatanon, a fort situated upon the Wabash and not too far below the town of La Fayette. Gladwin received a letter from Ouatanon’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Jenkins, informing him that on the 1st of June, there was an Indian conspiracy that he and several of his men were caught and made prisoners. The garrison surrendered. Oddly, the Indians apologized for their conduct, and they declared their action at the fort was contrary to their beliefs but the surrounding tribes forced them with threats to make them take up the hatchet. It was noted that these Indians were upset as they consoled the victims and, most likely, they came from areas farther out from the surrounding settlements with no contact or opinion on the effects of English insolence and encroachment.

More news came claiming Fort Miami was taken. This post stood on the River Maumee and commanded by Ensign Holmes. It was truly an outpost, the soldiers were isolated in an extensive wilderness of hundreds of miles and separated from any friendly associates. Occasionally, a frontiersman, or trader, or Indian would stop by from within the surrounding backwoods.

According to Ensign Holmes, he suspected wrongful intentions from the Indians and kept himself on guard. Then, on the 27th of May, a young Indian girl who lived with him came to tell him a squaw lay dangerously ill in a wigwam near the fort. She urged him to come help her. Holmes forgot his caution and followed her out of the fort. They walked to the edge of a meadow where, hidden from view by a stretch of woodlands, there were many Indian wigwams. They paused on the meadow as the girl pointed a deceiving finger to the wigwam where the sick woman lay below. Holmes continued to the wigwam without suspicion when, as he drew nearer, two gun shots fired from behind the wigwam and he fell to the ground lifeless. The gun shots were heard at the fort and the sergeant foolishly decided to leave the fort and investigate the shots since Ensign Holmes went to the Indian village to help the sick woman. The sergeant was taken prisoner amid savage yells and whoopings.

The remaining soldiers in the fort climbed upon the palisades to look out when they saw Godefroy, a Canadian, and two other white men appear. Godefroy called on the soldiers to surrender. He promised their lives would be spared, but, if they didn’t surrender, they would all be killed without mercy. The soldiers were terrified. They had no leader, so they decided to open the gate and surrender (Loss of the Posts, MS.; see Diary of the Siege, pp. 22-26).

It appears by a deposition taken at Detroit on the 11th June, that Godefroy, mentioned above, left Detroit with four other Canadians three or four days after the Detroit siege began. Their objective was to bring a French officer from the Illinois to induce Pontiac to abandon his hostile designs. However, at the mouth of the Maumee, they met John Welsh, an English trader, with two canoes, bound for Detroit. Godefroy and the four Canadians seized him, divided his furs among themselves and with a party of Indians who were with them. They then proceeded to Fort Miami, and aided the Indians to capture it. Welsh was afterwards carried to Detroit, where the Ottawas murdered him.

Rumors of Fort Presqu’ Isle loss initially reached Detroit on the 20th of June. Two days later, the Detroit garrison heard the dismal cries that announced scalps and prisoners. These sounds had become all too familiar. Indians were seen moving in numbers along the opposite bank of the river leading English prisoners. Ensign Christie, commanding officer at Presqu’ Isle, was among the soldiers who survived.

On the 3rd of June, Ensign Christie, wrote to his superior officer, Lieutenant Gordon, at Venango:

“I have sent to Niagara a letter to the Major, desiring some more ammunition and provisions, and have kept six men of Lieutenant Cuyler’s, as I expect a visit from the hell-hounds. I have ordered everybody here to move into the blockhouse, and shall be ready for them, come when they will.”

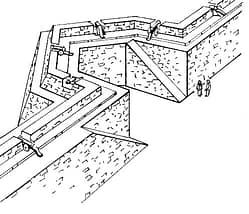

Fort Presqu’ Isle was situated on the southern shore of Lake Erie. It was an important post for an Ensign to command because it controlled the communication between the lake and Fort Pitt. The Blockhouse, which Christie referred to in his report, was supposedly impregnable against Indians. This blockhouse was built of massive logs, very large and strong. It had the usual projecting upper story that was similar in such structures. A vertical fire could be had upon the heads of assailants through openings in the projected part of the floor – like the machicoulis of a medieval castle. The blockhouse also had a type of bastion or rampart from which one or more of its walls could be defended by flank fire. The roof had shingles and could easily be set on fire, and at the top there was a sentry-box or look-out from which water could be thrown. On one side of the blockhouse there was the lake, and on the other side a small stream that flowed into the lake. Unfortunately, the bank along this stream rose to a high, steep ridge within 40 yards of the blockhouse that gave the assailants good concealment. On the other side of the lake, there was a nearby shore that also gave them a favorable advantage.

After Lieutenant Cuyler’s visit to the fort, Christie prepared for a stubborn defense with his present garrison of 27 men. The doors and sentry-box of the blockhouse were lined to make them bulletproof. Green turf was used to cover the angles of the roof to protect against fire arrows, and bark was used to create gutters for water streams to be sent in every direction. Christie also expected a visit from the ‘hell-hounds’ since he was informed 200 of them left Detroit for Fort Presqu’ Isle.

It was at first light of dawn, the 15th of June, when the Indians were initially discovered moving catlike across the mouth of the little stream where the traders’ flatbottom boats were secured along the shore. They continued under the cover of the lake’s banks and nearby sawpits. All was quiet, until the sun rose. It was then that the Indians became visible and began their customary shouting. Christie was reluctant to start the battle, so he ordered his men not to fire until the Indians had made the first move. Unfortunately, the consequence for that command was that the Indians would be too close to the blockhouse before they received gunfire from the garrison; which, when it happened, many of the Indians jumped into a ditch that sheltered them. The Indians then had an advantage to return fire into the blockhouse’s loopholes, throw stones and gravel, and they used something much more effective – fire-balls of pitch.

Some Indians entered the fort and sheltered themselves behind the bakery and other buildings where they kept up an active fire. Other Indians pulled down a small outhouse of plank that they made into a movable breastwork that they used as a cover to approach the blockhouse. At the same time, more Indians were set behind the ridges of the stream maintaining constant gunfire into every loophole as well as shooting burning arrows against the roof and sides of the blockhouse. Most of the fires were doused with water, while others slowly extinguished on their own after burning a small hole. The Indians’ next move was rolling logs to the top of the ridges where they constructed three strong breastworks to use as a shield so they could discharge their shot and throw their fireworks with greater accuracy. At times the Indians would dart across the intervening space and shelter themselves with other Indians in the ditch, but those who attempted the run were killed or wounded. But, now, the little garrison could see they were surrounded. The Indians were throwing up to the soldiers earth and stones behind the nearest breastwork, and the soldiers knew the enemy were undermining the blockhouse.

The barrels of water that were always kept in the blockhouse were nearly empty from dousing all the frequent fires. There was a well nearby on the parade ground, but the soldiers knew it be their death to approach it. Their only recourse was to dig a tunnel to it, so they tore the floor open. Meanwhile, the other soldiers were fixated on killing the enemy near the fort with their muskets from loopholes. It wasn’t long before the roof was on fire again and the men were forced to douse the fire with the last of their stored water. Moments later, another fire erupted and a brave soldier tore off the burning shingles with his bare hands, averting danger.

Night fell, and the men were fatigued from not a moment’s rest since dawn. Yet there was no relief. Guns flashed all night from the Indian intrenchments. By morning, there was a temporary break. The Indians were quiet. The soldiers suspected a new approach was being dug or built to attack the blockhouse. Afternoon came and the fighting resumed. A fire was set on the commanding officer’s house, which the Indians were able to reach from their new trenches. The building’s pine logs blazed wildly as the wind pushed the flames against the bastion of the blockhouse, scorching and blackening it as dark as charcoal when, finally, the commander’s house was engulfed in flames.

By this time, the garrison had successfully dug a passageway to the well and handled their water buckets with such team work that the fire was soon subdued, and the house collapsed into a glowing pile of embers. The men, although overly exhausted, continued to work and fight without a break inside the blockhouse, where it was an awful prison for them. The air was heated and thick with gunpowder smoke.

The firing on both sides lasted through the next day, and did not cease till midnight. At that time, a voice called out in French from the enemy’s intrenchments, a warning to the garrison that further resistance would be useless. Preparations were being made to set the entire blockhouse on fire, the first and second floor. Christie responded with a demand for someone among them who spoke English. A figure wearing Indian attire slowly came out from behind the breastwork. Christie recognized him as a former soldier from the French War who was captured and made prisoner by the Indians. This former soldier had clearly submitted to the savage way of life and adopted their cause. He willingly betrayed his own countrymen to fight with the enemy. The former soldier said if the fort surrendered, all lives would be spared. But should they choose to fight on, all would be burnt alive. Christie answered him by saying he will decide by morning. The Indians agreed and the fire was delayed.

Christie gathered his men and asked, “choose to give up the blockhouse, or remain in it and be burnt alive?” The men replied they would stay as long as they could bear the heat, then fight their way through (Evidence of Benjamin Gray, soldier in the 1st Battalion of the 60th Regiment before a Court of Inquiry held at Fort Pitt, 12th of Sept., 1763. Evidence of David Smart, soldier in the 60th Regiment, before a Court of Inquiry held at Fort Pitt, 24th of Dec., 1763, to take evidence relative to the loss of Presqú Isle which did not appear when the last court sat.).

A third witness, Edward Smyth, a corporal, testified that all but two of them were for holding out. He said that when his opinion was requested, his answer was that he had but one life to lose and he would be governed by the rest. However, he reminded them of the recent treachery at Detroit and the butchery at Fort William Henry, and, in his belief, they themselves should expect no better choice.

Morning came, and Christie sent out two soldiers to learn the truth about their preparations to burn the blockhouse. Upon reaching the breastwork, the two soldiers signaled a message back to Christie that his worst fears were confirmed. The soldiers demanded two principal chiefs meet with Christie midway between the breastwork and the blockhouse. The two chiefs appeared and Christie emerged, yielding the blockhouse; having first stipulated the lives of all the garrison to be spared and that they have the ability to retire unmolested to the nearest post.

Scraggy and pale, the weary soldiers came forth from the burned and bullet-perforated stronghold. Immediately, there was a rush of enemy marauders into the blockhouse sacking and stripping whatever loot they found. Benjamin Gray, a Scotch soldier, was enlisted by Christie to carry presents to the Indians but on seeing all the confusion, and hearing a piercing scream from the sergeant’s wife who was the only woman in the garrison, he escaped into the woods and safely made his way to Fort Pitt with the disastrous news from Fort Presqu’ Isle.

Christie and his men had good cause to be thankful that they were not butchered on the spot. After being detained by the Indians for some time, they were finally carried as prisoners to Detroit, where Christie soon made his escape and gained the fort in safety.

Loss of the Posts: MS. Pontiac; MS. Report of Ensign Christie, MS.; Testimony of Edward Smyth, MS. This last evidence was taken by order of Colonel Bouquet, commanding the battalion of the Royal American Regiment to which Christie belonged. Christie’s surrender had been thought censurable both by General Amherst and by Bouquet. According to Christie’s statements, it was unavoidable; but according to those of Smyth, and also of the two soldiers, Gray and Smart, the situation, though extremely critical, seems not to have been desperate. Smyth’s testimony bears date 30 March, 1765, nearly two years after the event. Some allowance is therefore to be made for lapses of memory. He places the beginning of the attack on the twenty-first of June, instead of the fifteenth,—an evident mistake. The Diary of the Siege of Detroit says that Christie did not make his escape, but was brought in and surrendered by six Huron chiefs on the ninth of July.

After Fort Presqu’ Isle ceded to the Indians, the neighboring posts of Le Boeuf and Venango faced their fate. Meanwhile, farther southward, at the forks of the Ohio, a host of Delaware and Shawanoe warriors were gathering around Fort Pitt. Havoc and blood reigned along the whole frontier.

Continue to Part 3

CHIEF PONTIAC CONTINUES TO BLOCKADE FORT DETROIT, 1763

References

At this point in Pontiac’s history, I decided to use Francis Parkman’s THE CONSPIRACY OF PONTIAC as my sole reference and guide for the Parts that followed Part 1. Parkman’s window gave me a much clearer window into the actual events, its characters, human behavior, strategies and tactics that I found dependable overall – even 200+ years later. I wanted to understand Pontiac: his character, motives, and beliefs. And I wanted to know the indigenous force of the American Indian and their historical significance: their way of life, drama, ambition, and savagery. I wanted to share a story, not just an article on facts.

Parkman, Francis. THE CONSPIRACY OF PONTIAC (1851). Collier Books, New York, NY (1962).