The war was over. France surrendered to Britain. And Pontiac’s deep-seated hatred for the English, his want for revenge, his ambition to succeed, and his loyalty to the French pushed him to move forward with war.

- Post Contents -

The english take possession of the western posts

The French and Indian War was over. Canada, with all her dependencies, finally yielded to the British Crown and France dutifully remained to fulfill the terms of surrender. The execution of this difficult undertaking was given to a provincial officer from Rogers Rangers, Major Robert Rogers.

Rogers, originally from New Hampshire, commanded a company of provincial Rangers who were recruited from local communities and nearby states. He was considered a highly reputable partisan officer. John Stark and Israel Putnam were close associates in the woodland warfare and they shared a multitude of perilous adventures and narrow escapes. Rogers Rangers were part hunters and part woodsmen trained in a discipline that was completely their own. They were armed like Indians; hatchet, knife, and gun. They engaged in daily hardships, and operated in the dense forests and mountainous terrains. The Rangers were required to be fearless fighting men who made it their business to know the enemy very well and who could take on missions as scouts and skirmishers (MS. Gage Papers).

Their main region of action was the mountains surrounding Lake George, between the hostile forts of Ticonderoga and William Henry. Deep in these woods the French and Indian yells were carried far, and so were the responding shouts from Rogers Rangers. During the summer months, the Rangers passed down the lake in whale boats or canoes, or walked in single file down foot paths throughout the backwoods like the savages themselves. In winter, they travelled through swamps on snowshoes, skated along the frozen surface of the lake and camped at night among the snow-drifts. The Rangers intercepted French messengers, confronted French scouting parties, and took prisoners from under the walls of Fort Ticonderoga. The Rogers Rangers exploits became infamous throughout the American colonies, and their name was always mentioned with utmost respect.

A cold, fall season was fully upon them. There was a biting wind on Lake Erie’s rough water and from their boats they could see the trees on shore almost naked. By the seventh of November, their boats reached the mouth of a river Rogers called, Chogage, which was an unknown region to the British. That day was rainy and gloomy. Rogers decided to rest the Rangers until the weather improved. His men prepared an encampment in the nearby forest.

It wasn’t long after the Rangers setup camp, when a party of Indian chiefs and warriors arrived. The Indians announced themselves as an embassy from Pontiac, ruler of all this country, and they were sent to deliver a message to the English. An Indian chief came forward and said the English should advance no further until they had an interview with the great chief. The Indian embassy then withdrew back into the forest.

Before the day ended, Pontiac appeared in the Rangers camp. He greeted Rogers formally, but with an arrogant attitude. He demanded to know what Rogers’ business was in his country and how he dared to enter it without his permission. Rogers quickly informed Pontiac that the French was defeated and Canada surrendered, and they were on their way to take possession of Fort Detroit to restore peace to the white men and to the Indians as well. Pontiac listened, then replied that he would stand in the way of the English until morning. Rogers didn’t know what to think. Pontiac asked if the strangers were in need of anything that his country could provide. Rogers shook his head. Pontiac withdrew with his chiefs back into the woods at nightfall. The Rangers were uneasy. They suspected treachery, and throughout the night they placed guardsmen to secure their camp (Rogers, R. Journals; Account of North America. Pp. 240-243).

It was dawn when Pontiac returned to the Rangers camp with his attendant chiefs. He went directly to Rogers and said he was willing to live at peace with the English. He would allow the English in his country as long as they treated him with due respect and honor. Then the Indian chiefs smoked the calumet with the Rangers and harmony seemed settled between them (Ibid).

The American forest had not seen a man more shrewd, ambitious, or tactical than Pontiac. He was, in word and deed, a solid ally of the French. Yet, Pontiac was ignorant of the world’s developing advancements and changes, and he could only see in his world that the French power was declining. He understood it was useless to support a falling cause and he felt it was best to make friends with the English. It was probably true that the English could have been powerful allies who would support his ambitious projects and increase his influence among the other tribes. But Pontiac was a proud man. He expected newcomers to treat him with the same civilized respect that the French gave him. However, this was not to be so. Pontiac’s expectations from the English were destined to be doomed (Ibid).

A cold rain set in for several days. The Rangers were delayed in their encampment. During this time, Rogers had several visits with Pontiac where he observed Rogers strength and intellect, as well as his control over his men (Ibid).

On the 12th of November, the Rangers were once again on the move and within a few days they reached the western end of Lake Erie. They heard rumors of Indians from Detroit rising up with arms against them with 400 warriors lying in ambush at the entrance to the river so they would be cut off. But Pontiac intervened and used his powerful influence on behalf of the Rangers, forcing the warriors to abandon their attack. The Rangers continued on their way to Detroit without knowing what had awaited them (Ibid).

Governor of Louisiana 1743-1755 –

Governor-General of Canada

1755-1760

Canadian Museum of History

The Rangers entered the mouth of the Detroit River. Rogers sent a message to Captain Campbell with a copy of the French surrender and the letter from Marquis de Vaudreuil, verifying that Fort Detroit must be given up according to the terms agreed upon between him and General Amherst. French Captain Picoté de Belestre was forced to yield Fort Detroit and his garrison to the incoming English commander (Ibid).

The Rangers’ whale boats moved slowly between the low banks of the Detroit River until the marsh and forest landscape opened to the isolated settlements that appeared on the river’s banks. On their right was the village of Wyandots, and to their left the lodges of the Pottawattamies. Then further on they saw the flag of France and knew it was flying for the last time (Ibid).

The day was 29 November 1760. The Rangers landed their whale boats along the shore and pitched their tents in a field, while two officers and a small detachment took a boat and went across the river to take possession of the fort (Ibid).

Though obedient to their summons, they were crudely resentful. The French garrison defiled the field before they laid down their arms. The French flag was lowered from the flagstaff and the cross of St. George rose in its place, while triumphant yells came from 700 Indian warriors (Ottawas, Potawatomis, Hurons (or Wyandots), and Chippewas [or Ojibways]) who came to watch the event. The Canadian militia was then called to line up and be disarmed. The Indians did not understand why the English, who were the conquerors in the French and Indian war, did not kill their defeated enemies at once. Yet, such a ceremony of mercy and power was more effective for the English in gaining the needed respect from the Indians (Ibid).

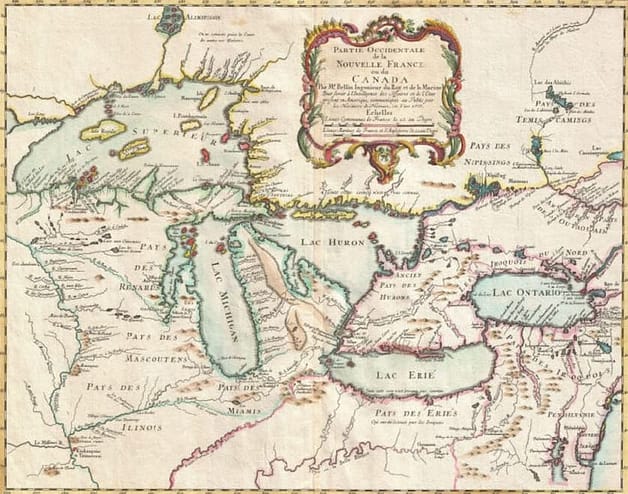

The French garrison was sent away as prisoners. The Canadian inhabitants were permitted to keep their farms and houses on the condition that they swear loyalty to the British Crown. And an officer was ordered southward to take possession of Forts Miami and Ouatanon – important forts that guarded communication between Lake Erie and the Ohio – while Rogers took a small party northward to take over the French garrison at Fort Michilimackinac. But the icy storms and thickening ice on Lake Huron forced Rogers and his party back to Fort Detroit.

Along with Michilimackinac, there were three other remote posts, the St. Marie, Green Bay, and St. Joseph that had to remain temporarily under French control. At the next season, the 60th Regiment – initially called the Royal Americans – was detached to take possession of them.

The process of a conquest was complete. All of France’s claims to the wilderness beyond the Alleghanies and its arteries of streams, were now all under England’s sovereignty. A region that embraced thousands of miles was to be controlled by some five to six hundred men. There appeared to be little apprehension from the English about the Indians in the woods. But after two years, English complacency was a fatal mistake.

indian conspiracy, 1760-1763

It didn’t take long for the Indians to become discontented and bitter against the English. Many Indian tribes were allies of France and they fought against the British. They remembered the gifts the French gave them to gain favor, but the British did not offer gifts. They remembered the remote Indian nations in the west who traveled many miles in their canoes to join the fight against the enemies of France. And the Indians remembered their hostility against the English during the war between the French and English, which they have quietly preserved.

Even from the beginning of the war with France, it would have been advantageous for the British to be careful with their conduct toward the tribes but the British considered the Indian not that important, and they treated them with indifference and neglect. And it appeared that the British would continue on the same course. To the British, friendship with the Indian seemed to be of no importance. The presents that were always customary from the French, the Indians expected to be continued. But the British either withheld them or they were slowly and reluctantly dispensed. And to make the situation worse, agents and officers of the government often took the gifts for themselves and sold them to the Indians at a higher price.

When the French had ownership of the remote forts, they supplied the Indians with guns, ammunition, and clothing. And over a long period of time, these gifts were utterly detrimental to the Indians way of life. The Indians depended too much on the support of the white man that they soon forgot to live and dress like the old ways of their forefathers. The Indians were addicted to the white man’s merchandise. And the abrupt withdrawal of these supplies was a distressing catastrophe. Its consequences were want, suffering, and death; and this outcome alone would have been enough to grow discontent (Extract from a MS. Letter – Sir William Johnson to Governor Colden, 24 Dec. 1763).

(1719-1765)

In January, 1763, Colonel Henry Bouquet, commander in Pennsylvania, wrote to General Amherst, command-in-chief, regarding the discontent produced among the Indians because of the suppression of presents:

As to appropriating a particular sum to be laid out yearly to the warriors in presents, & c., that I can by no means agree to; nor can I think it necessary to give them any presents by way of Bribes, for if they do not behave properly they are to be punished.

The English fur trade was never well regulated and, at this point, it was in its worst condition. Many traders, as well as those working for them, were boorish roughnecks who challenged each other with greed, violence, and corruption. They cheated the Indians, insulted them, outright robbed them, and mistreated their families. Compared to the French traders’ behavior, who were better regulated, it was a most favorable representation of the character of a nation.

The next disappointment in behavior by the British were their officers and soldiers of the garrisons. When the warriors previously came to the forts, they were warmly welcomed by the French and given much attention and respect. The French graciously overlooked any inconvenience the Indians’ presence may have caused and ignored their uncustomary traits. But now they were unwelcome and coldly received by the British. Yet, what seemed to be the biggest contributor to the growing discontent of the tribes was the trespassing from settlers upon their lands.

The English treat us with much Disrespect, and we have the greatest Reason to believe, by their Behavior, they intend to Cut us off entirely; They have possessed themselves of our Country, it is now in our power to Dispossess them and Recover it, if we will but Embrace the opportunity before they have time to assemble together, and fortify themselves, there is no time to be lost, let us Strike immediately.

Speech from a Seneca chief to the Wyandots and Ottawas of Detroit; July, 1761.

The Indians were angry and fearful over the steady progress of the white man, whose settlements passed the Susquehanna and were quickly moving to the Alleghanies, devouring the forest like a spreading sickness. This anger from the Delawares was shared by their former enemy, the Iroquois of the Six Nations (Minutes of Conference with the Six Nations at Hartford, 1763, MS. Letter – Hamilton to Amherst, 10 May 1761).

Unfortunately for France, Canada was gone and beyond hope of recovery. Yet, the French secretly hoped for some sort of vindication over its loss. The Indian’s discontent gave the French immense satisfaction. They tried provoking the Indians with rumors of British offenses against them to further inflame their resentment. Moreover, most of the inhabitants in the French settlements around the lakes and the Mississippi were involved with the fur trade, and they feared the British as hardened rivals. The French inhabitants wanted to see the British driven out of the country as well, and this deed would utterly gratify them.

So then, the Canadian fur traders and the Canadian inhabitants took it upon themselves to circulate among the Indian villages holding secret councils with them in the woods. They urged the Indians to go to war against the English because they had a plan to annihilate the Indian race, such as surround them with settlements and forts in order to force them into submission. The French Canadians also instigated the Cherokees to attack and destroy the Ohio Valley tribes. Baseless lies were intentionally spread among the Indians and they believed them (Croghan, Journal. Hildreth, Pioneer History, 68. Also Butler, Historical Kentucky, Appendix).

The Canadians here are eternally telling lies to the Indians. One La Pointe told the Indians a few days ago that we should all be prisoners in a short time (showing when the corn was about a foot high), that there was a great army to come from the Mississippi, and that they were to have a great number of Indians with them; therefore advised them not to help us. That they would soon take Detroit and these small posts, and then they would take Quebec, Montreal, &c., and go into our country. This, I am informed, they tell them from one end of the year to the other. He adds that the Indians will rather give six beaver-skins for a blanket to a Frenchman than three to an Englishman.

Letter from Lieutenant Edward Jenkins, commander at Fort Ouatanon on the Wabash, to Major Gladwin, commander at Detroit; 28 March 1763

Since Indians were generally known to be susceptible to superstitions, it wasn’t unusual that another prophet would arise among them. This one was among the Delawares, and his objective was not entirely political. His supporters were to strengthen and purify their character, making themselves acceptable to the Great Spirit, whose messenger he claimed was himself. The prophet directed them to put aside the weapons and garments received from the white men and return to the simple way of life of their ancestors. By doing this as well as observing his other principles, the tribes would be restored to their ancient greatness and power, enabling them drive out the white men from their territory. Many followers came from near and far to gather together in large encampments to listen to this prophet. But the action to reject the use of the white man’s firearms was unthinkable and disadvantageous for them. The Indians could not comply (J. McCullough’s Narrative. See Incidents of Border Life; 98 [McCullough was prisoner among the Delawares at the time of the prophet’s appearance]).

by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1765 –

Canada Archives

The British assumed that the Indians would not remain quiet for too long. In the summer of 1761, Captain Donald Campbell, then commander at Fort Detroit, was sent a message informing him that a delegation of Senecas arrived at the neighboring village of the Wyandots to incite the Senecas into destroying Fort Detroit and its garrison. Upon further investigation, Fort Niagara, Fort Pitt, and other posts were to share the same fate as Detroit. Campbell immediately sent messengers to General Jeffrey Amherst, commander of the British Army in America, as well as the commanding officers stationed at other forts warning of the impending danger from the Indians. The quick action halted the conspiracy at once (MS. Minutes of Council held by Deputies of the Six Nations, Wyandots, Ottawas, Ojibwas, and Pottawattamies at Wyandot town near Detroit; 3 July 1761).

By the next summer in 1762, another familiar scheme was detected and suppressed. Then one year after the discovery of the first scheme another plan was developed, but this strategy was found to be greater in size, clever, and much more comprehensive – this plot had never been conceived or executed by an American Indian before. It’s goal was to attack all English forts on the same day. Then when all the garrisons were destroyed, the Indians would attack the defenseless frontier and ravage the settlements until they were wastelands. The Indians firmly believed the English would then be driven into the sea and their country restored to its former ancestors way of life.

Pontiac was the dominant chief of the Ottawas since he had long been the acting head of the Ottawas, Ojibwas, and Pottawattamies. These three tribes were a united but loose confederacy, and those around Pontiac regarded his authority as overbearing. His rising power reached beyond the limits of the three tribes and out to the nations of the Illinois country. Pontiac had become known and respected.

Although Pontiac was born the son of a chief, it would in no way account for his magnitude of power. Many a chief’s son descended to a minor position in the tribe because of the abilities from an offspring of a common warrior who proved his skills superior to the chief’s son, whereby succeeding the chief son’s position.

Among all the Indian tribes, personal merit was essential in order to gain and preserve dignity. Courage, resolve, wisdom, address, and eloquence were necessary for distinction, and Pontiac was pre-eminently endowed. Pontiac’s intellect was plentiful and strong. He possessed great energy with an exacting force of mind. Although he was capable of benevolent acts, Pontiac was wild and barbaric. He shared the Indian’s passions and prejudices, as well as their fierceness and treachery (Drake, Life of Tecumseh, 138).

Until Major Rogers came in to the country, Pontiac was a firm friend of the French. Before the French war began, he saved the Detroit garrison from imminent danger of attack from several discontented tribes of the north. During the war, he fought on the side of France and it was rumored that he commanded the Ottawas at the defeat of General Braddock. Pontiac was highly honored by the French officers and he received especial marks of esteem from the Marquis de Montcalm.

When the two rival European nations co-existed together in America their policy was to pacify with goodwill, and in order to gain the Indians alliance, they avoided offending them by injustice and encroachment. But after the downfall of Canada, the Indian tribes quickly descended from their position of power and importance. The British gained sovereignty and the Indians were no longer important allies. They were treated as simple barbarians. They were abandoned to their own weak resources and divided stability. Their best hunting grounds were trespassed. They saw along the eastern ridges of the Alleghanies smoke that rose in high columns from the settlers’ clearings within the forest. As the tribes receded and dwindled away against the steady progress of colonial power, they remained in the belief that one day they would rise again – uproot and overthrow their destroyers.

Pontiac now embraced a wider and deeper view. The peril of the times unfolded before him and he resolved to unite the tribes in one grand effort to avert disaster against the Indians. He didn’t entertain the absurd idea that the Indians wanted to drive the English into the sea, but he could adopt the only plan consistent with reason to restore the French supremacy in the west.

Unfortunately, Pontiac believed the lies from the Canadians. They intentionally misled Pontiac with false assurances that King Louis’s armies were already advancing to recover Canada. They said the French and their red brethren would fight side by side to drive the English dogs back to their own limited boundaries. Pontiac’s deep-seated hatred for the English, his want for revenge, his ambition to succeed, and his loyalty to the French pushed him to move forward with war.

By the end of 1762, Pontiac sent ambassadors out to the Ohio and its tributaries, to the regions of the upper lakes, to the borders of Ottawa River, and as far south as the mouth of the Mississippi (M.S. Letter – M. D’Abbadie to M. Neyon, 1764). These ambassadors carried with them the war-belt of wampum and the red-stained tomahawk in token of war. They journeyed from camp to camp and village to village. Wherever they stopped, the sachems and old men assembled to hear the words of the great Pontiac. The leader of the ambassadors then threw down the tomahawk on the ground before the council, and held high the war-belt in his hand as he delivered with passion his speech with which he was charged. The speech was heard everywhere with approval; the belt accepted, the hatchet snatched up, and the assembly of chiefs pledged to take part in the war. The initial blow was to be struck at a particular time in the month of May following – indicated by the changes of the moon. All the tribes would then rise together, as each tribe destroyed the British garrison in its neighborhood. Then, in a general rush they would all turn against the settlements of the frontier.

Northern Indian Superintendent – 1756

The tribes that banded together against the British were the Algonquins, the Wyandots, the Senecas, and the tribes of the lower Mississippi. The only members of the Iroquois confederacy who joined the league were the Senecas. The rest of the Iroquois confederacy remain quiet because of Sir William Johnson’s influence.

As the Indians waited for their secret outbreak, they casually resumed their daily routines of lounging about the forts, doing their usual begging for tobacco, gunpowder, and whiskey. Occasionally, a small, suspicious disturbance would startle the garrisons and alert them to danger. Then one day, an English trader arrived at a fort from one of the Indian villages and reported that he suspected the Indians were contemplating mischief because of their unusual mannerisms and behavior. A scoundrel half-breed was also heard boasting in his cups that before next summer, he would have English hair to fringe his hunting-frock. On another occasion, the plot was almost discovered.

It was early March in 1763 when Ensign Robert Holmes, commander at Fort Miami, was informed by a friendly Indian that the warriors in the neighboring village had recently received a war-belt and with it a message urging them to destroy Holmes and the garrison. They were in preparation to do so. Holmes summoned the Indians together and boldly accused them of plotting a revolt. The Indians did what they always did in similar situations and that was to falsely confess their fault, while showing much remorse and blaming a neighboring tribe. They continued the pretension with a declaration of eternal friendship to the English. Holmes wrote his discovery to Major Gladwin, who forwarded the information to Sir Jeffrey Amherst. Gladwin expressed his opinion that there existed a common irritation among the Indians, but the situation would soon blow over and the Indians nearby his own post were perfectly tranquil (MS. Speech of a Miami Chief to Ensign Homes; Ms. Letter – Holmes to Gladwin, 16 March 1763. Gladwin to Amherst, 21 March 1763).

Fort Miamis, March 30th, 1763.

Since my Last Letter to You, wherein I Acquainted You of the Bloody Belt being in this Village, I have made all the search I could about it, and have found it out to be True; Whereon I Assembled all the Chiefs of the nation, & after a long and troublesome Spell with them, I Obtained the Belt, with a Speech, as You will Receive Enclosed; This Affair is very timely Stopt, and I hope the News of a Peace will put a Stop to any further Troubles with these Indians, who are the Principal Ones of Setting Mischief on Foot. I send you the Belt, with this Packet, which I hope you will Forward to the General.

Extraction from a Manuscript Letter – Ensign Holmes commanding at Miamis, to Major Gladwin

preparation for war, 1763

The Indians lived mainly by hunting. They were widely scattered across their lands and were divided into many tribes. They were loose and disjointed as a whole, yet, they held together by no strong rule of solidarity or central governance to unite their force. With such little effectiveness against an enemy, it would be difficult to oppose them. There were chiefs whose position was mostly a hereditary custom, but their authority was entirely a moral nature and enforced by no mandated law. Their basic function was to advise, not to command. Their influence was primarily to refer to the etiquette of hero-worship, which was inborn to the Indian character. There was a reverence for age where the honor element largely prevailed. And it was their position to declare war and peace, but, when war was declared, they had no power to carry the declaration into effect.

The warriors fought if they wanted to do so, but if they preferred to remain quiet, no man could force them to raise the hatchet. Though a simple partisan, the war-chief’s part was to lead them to battle, yet he held distinction because of his bravery and exploits. When several war parties from different bands or tribes were united in a common campaign, the chiefs elected a leader who would command over all the tribes; however, if this selection was found unfit because of an uncommon reputation and ability – such as commands that were disregarded and/or authority held insignificant – his warriors would often desert in mass and, before reaching the enemy’s country, it was known that they would dwindle away until the horde of Indians were reduced to a small scalping party.

The wild love of freedom and the impatience of all control marked the Indian race, rendering them completely intolerant to military discipline. Indians acting in large masses are commonly unpredictable – devoid of caution and foresight. Thus, to provide supplies for a war campaign was not included in their system, and the attack must be immediate or it would not be struck at all; to postpone a victory is to insure defeat. When acting in small, detached parties, the Indian warrior puts forth his energies and displays his skill, endurance, and bravery and it is then that he becomes a dreaded enemy. The warrior is fired with the hope of many scalps. No hardship will divert him from his purpose and no danger will subdue his patience and courage.

The prevailing English irritation gave the Indians assurance that they were not to remain idle. Although there was little risk that they would capture a strong and well-defended fort, there was, on the other hand, the assumption of wide-spread pillaging and a destructive war. It was the Indian leader’s part to work upon the passions of their people, to keep alive the English irritation, and to increase their appetite for blood and glory. However, it was no easy task to penetrate the thick woods in search of a foe, to be as alert and active as a lynx, even though the lynx would seldom stand and fight, yet whose deadly shot and triumphant whoop were the first and, most often, the last evidence of his presence. Only to vanish into the black recesses of the forest and pine swamps from the approaching hostile forces in order to renew his attacks.

Over on the other side, the British colonies were ill-fitted to bear the brunt of another impending war. The army that conquered Canada was dissolved, the provincials disbanded, and most regulars sent home. A few fragments of regiments, miserably wasted by war and sickness, arrived from the West Indies and were ready for their order to return to England and be disbanded. But they remained as small troops that could furnish weakened garrisons on frontier forts in the Indian country (Mante, 485). Sir Jeffrey Amherst was the head of this neglected army and was well-fitted for the emergency; however, he kept the Indians in supreme distaste with uncontrolled treatment for them, including appeasement, and he held no interest in provoking war.

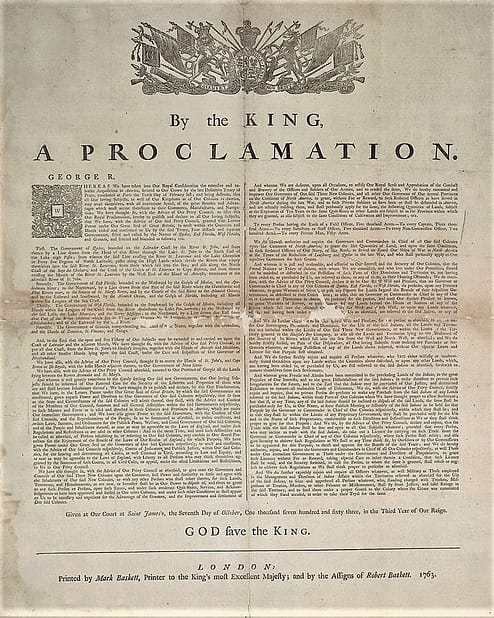

While the Indian war was getting very close to actually mobilizing its network of tribes against the English, an event occurred that had an important impact over its progress – the signing of the treaty of peace at Paris, on the tenth of February, 1763. With this treaty, France formally resigned her claims to the territories east of the Mississippi, and the great Mississippi became the western boundary of British colonial possessions. Britain portioned into separate governments their new acquisitions and left the Valley of the Ohio and its adjacent regions as Indian domain.

Then, by the seventh of October, 1763, the King’s Proclamation claimed the intrusion of settlers on these lands to be strictly prohibited. If this treaty was adopted sooner it would have been quite probable that it could have prevented the Indian war from being excessively violent, but, most likely, the treaty would have made it undeniably clear to the Indians that the French could never repossess Canada. The treaty would have dashed every hope the Indians entertained for assistance from the French and, at the same time, would have calmed their minds with the removal of the main cause of irritation, the settlers’ trespass. Unfortunately, the treaty was too late. The Indian’s fire was already inflamed for war and savagery. And while the sovereigns of France, Britain, and Spain were signing the treaty at Paris, countless Indian warriors in the American forests were singing their war song and whetting their scalping knives.

council at ecorse river, 1763

With the first sign of spring, it was time to begin the war. Pontiac sent his messengers with wampum belts and gifts of tobacco to visit as many hunting camps in the northern woods, calling chiefs and warriors to attend the general meeting. The appointed place was on the banks of the little River Ecorse, not far from Detroit. Pontiac took his squaws and children, while band after band of Indians came straggling in until the meadow was densely marked with temporary, flimsy wigwams (Pontiac, MS.). The gathering warriors smoked, laughed in groups, and used their lazy hours gambling, feasting, and sharing adventure stories.

According to a great Roman historian who observed the ancient Germans, when men were summoned to a public meeting, it was important that they followed the custom of falling behind the appointed time in order to display their independence. This remark holds true, especially with American Indians. It took several days before the assembly was complete. There were different bands and tribes all gathered on one common camp ground, and it would undoubtedly need a sage leader skilled in preventing open conflicts from rising jealousies. It was known that the Indians were quick to quarrel and more inclined to forget the purpose of the future.

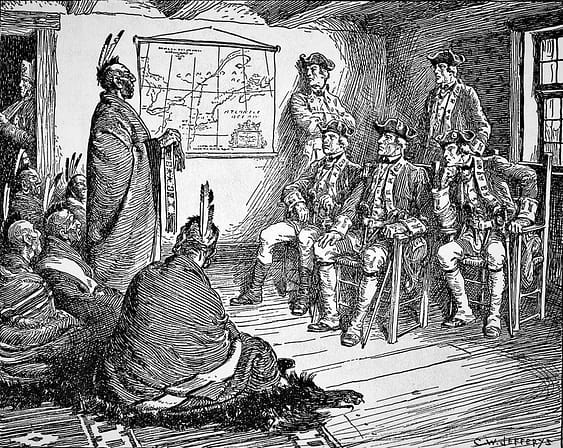

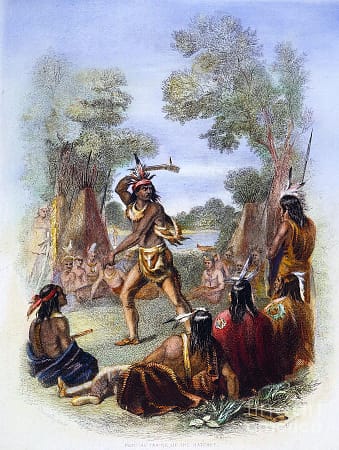

The council happened on the 27th of April. Forerunners of the camp, the elders, passed among the lodges calling the warriors in loud voices to attend the meeting. The Ojibwas, Ottawas, and Wyandots were soon seated in a wide circle on the grass of the meadow. Row upon row, each face seemed as solid as wood, grave and silent. Pipes with ornamental stems were lit and passed from hand to hand.

by Benson J. Lossing LL.D, NY (1875)

Pontiac then rose and walked forward into the center of the council. He was of middle height with a muscular figure of strength and balanced proportion. His complexion was darker than usual with his race and his features were hardened with a look of fearlessness. His typical garments included a rope cincture girt about his loins and his long, black hair fell loosely down his back, but, on such an occasion as this, he wanted to be dressed in what was befitting his position – primped and painted in the full costume of war.

Pontiac looked upon the assembly and began to speak with a loud and impassioned voice. He declared the English commandant treated him with neglect and contempt. The garrison soldiers abused the Indians. The English expelled the French and now they waited for an excuse to turn against the Indians and destroy them. He held high a broad belt of wampum and told the council he received it from the great father, the King of France, as a token to have heard the voices of his red children and that his sleep was at an end. His great war canoes would soon sail up the St. Lawrence to win back Canada and wreak vengeance on his enemies. The Indians and their French brethren, Pontiac continued, would fight once more side by side as they had always fought. They would strike the English from an ambush, like they would at a flock of pigeons in the woods.

Pontiac was not alone in his views about being an adversary against civilization or being an advocate for primitive barbarism. Many of the most notable men that have risen among the Indians agreed with such an opinion, such as Red Jacket and Tecumseh. There was nothing progressive in the rigid, inflexible nature of the Indian. He was inherently closed to ideas of improvement, and nearly every change forced upon him was a change for the worst.

Habitually every spring, after the winter hunt ended, the Indians returned to their villages or encampments near Fort Detroit. And after the council disbanded, the Indians resumed their usual appearance about the fort. On the first day of May, Pontiac came to the gate with forty men from the Ottawa tribe and requested permission to enter and dance the calumet dance before the officers of the garrison. There was some hesitation to admit the Indians but, eventually, Pontiac was granted admittance, and he and his warriors set up the dance in a corner of the street very close to the commandant’s house, Major Henry Gladwin. Thirty warriors began their dance of recounted exploits of bravery, while the officers and men gathered around them. Meanwhile, ten Ottawas walked about the fort observing everything in it. When the dance concluded, all the Indians calmly withdrew from the fort leaving the English without any suspicious thoughts (Pontiac, MS.).

(~1730-1791)

by John Hall (1739-1797)

Detroit Institute of the Arts

A few days later, Pontiac sent messengers to Indian cabins calling the principal chiefs to another council in the Pottawattamie village. A hundred chiefs sat around inside a large bark council house that was erected specifically for such occasions. In the center was a traditional fire that spread dark shadows of the men along its walls as the chiefs passed a pipe from hand to hand. There were young Indian men stationed as sentinels outside the structure to prevent any interruptions. Pontiac once again addressed the chiefs. He heavily promoted hostile actions against the English and finished by revealing his plan to destroy Fort Detroit.

This was Pontiac’s plan: Pontiac would demand a council with the fort commandant regarding matters of great importance, and that would enable him and his principal chiefs to gain prompt admittance into the fort. They would, he continued, all carry weapons concealed beneath their blankets. And while Pontiac addressed the commandant in the council room, he would give a certain signal upon which the chiefs would raise the war-whoop and rush the officers present, striking them down. The Indians at the gate and those loitering outdoors among the houses would assail the confused and half-armed soldiers after hearing the yelling and firing inside the building. Thus, Fort Detroit would fall like easy prey.

No chief was foolish enough to oppose their great leader’s war plan. Hence, Pontiac’s plan was eagerly adopted. The chiefs wrapped their blankets around them and withdrew to their respective villages. It was time to prepare for the destruction of Fort Detroit.

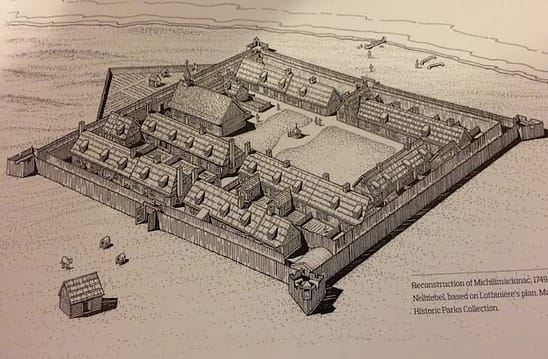

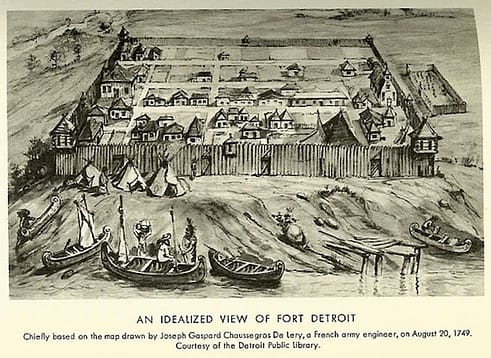

fort detroit, 1763

It was the close of 1760 when a party of British troops took possession of Fort Detroit. Its garrison of regulars and provincial rangers were quartered in the well-built barracks within the fort. The fort’s structural form was nearly square with approximately a hundred small houses. The palisade that surrounded it was about 25 feet high, and at each corner there was a wooden bastion and blockhouse over each gateway. The houses were mainly built of wood and roofed with bark or straw thatch. The streets were very narrow with the exception of a wide passage way, chemin du ronde, that surrounded the town between the houses and the palisade. Aside from the barracks, the only public buildings were the council house and a roughhewn, little church.

The garrison housed 120 soldiers, among those about 40 fur traders and engagés (French male indentured servants, canoe/boat men in the fur trade) who were not trusted, as well as the Canadian residents within the fort, in the event of an Indian attack. There were also two small, armed schooners, the Beaver and the Gladwin, which were at anchor in the stream with several light pieces of artillery mounted on the bastions. Such was Detroit. A place with little defense and no resistance to an enemy.

On the afternoon of the fifth of May, a Canadian woman, wife of St. Aubin – one of the principal settlers, crossed over from the west side and visited the Ottawa village to obtain a supply of maple sugar and venison from the Indians. She was surprised to find several warriors preoccupied filing off the muzzles of their guns. They were reducing the muzzles, stock and all, to the length of about a yard. She left the village and returned home by evening. She casually mentioned to several of her neighbors what she saw at the Ottawa village and one of the neighbors, the blacksmith, remarked that many of the Indians visited his shop recently and tried to borrow files and saws, but they wouldn’t explain why they needed them (St. Aubin’s Account, MS.; Appendix C). The incidents aroused suspicion among the veteran Canadians, but no alarm was made to suggest an Indian plan. It may have been that there were those who didn’t want to get involved and those that held little interest in the preservation of peace. However, an old and wealthy settler, M. Gouin, went to the commandant and warned him to be on guard, but, Gladwin, a moody individual, gave no heed to the old settler’s advice (Gouin’s Account, MS.).

There lived an Ojibwa girl in the Pottawattamie village who was blessed with more beauty than was common. Gladwin was attracted to her and he formed a relationship with her. She became very attached to him. On the afternoon of the sixth, Catharine – a name the officers gave her – came to the fort and visited Gladwin’s quarters. She brought with her a pair of elk-skin moccasins that were decorated with porcupine ornaments that he requested her to make. Gladwin noticed something unusual about her look and manner. Her face was downcast and her eyes sad. She said little, and soon removed herself from the house and lingered on the street corner. The sentinel watched her till the hour for closing the gates. Gladwin was concerned with her behavior and called her to him. He pressed her to say what was weighing upon her mind. She continued to remain silent until, finally, she relented to Gladwin’s urgency and promises not to betray her when she at last revealed her long-held secret.

Tomorrow … Pontiac will come to the fort with sixty of his chiefs. Each will be armed with a gun, cut short, and hidden under his blanket. Pontiac will demand to hold a council and after he delivers his speech, he will offer a peace-belt of wampum holding it in a reversed position. This will be the signal for attack. The chiefs will spring up and fire upon the officers, and the Indians in the street will fall upon the garrison. Every Englishman will be killed, but not the scalp of a single Frenchman will be touched.

Letter to the writer from H.R. Schoolcraft, Esq., containing the traditional account from the lips of the interpreter, Henry Conner; Carver, Travels, 155 [London, 1778]

This was the story told in 1768 to the traveler Carver at Detroit. It was preserved in local tradition, but not verified by any letters or diaries. What was certain was the secret information that Gladwin received on the night of the sixth of May. An attempt would be made the next day to capture the fort by treachery. Gladwin called some of his officers and told them what he heard. The fort’s defenses were weak and extensive. The garrison was far too weak to repel a typical assault. The Indian forces at that time varied from 600 to 2,000, and Gladwin greatly feared some wild impulse could very likely accelerate their plan and the Indians would storm the fort before morning. Every preparation was quickly made to satisfy the sudden emergency. Half the garrison was ordered under arms, while all the officers prepared to spend the night on the ramparts.

Night descended on the ruthless Indians and the sleepless British. From sunset till dawn, an anxious watch was kept. Though the soldiers and sentinels were kept uniformed of the danger, they wondered why the officers were repeatedly vigilant on their posts. Even Gladwin mounted his wooden ramparts, over and over, looking into the black of night. All was quiet and peaceful, except for the piping of frogs along the river bank. There were pauses of a night wind that swept gently across the bastion carrying a foreboding sound to one’s ear, a malevolent boom from an Indian drum. Then the rise of a wild chorus of vibrating yells as the warriors danced their war-dance around distant campfires in readiness for the morrow’s work (Maxwell’s Account, MS; Appendix C).

pontiac’s treachery, 1763

The night passed without alarm. As the rising sun dissolved the morning mist, the garrison carefully watched a fleet of birch-dug canoes cross the river from the eastern shore, all within range of the canon shot above the fort. Only two or three warriors were seen in each canoe. The canoes all moved slowly, suggesting a heavy load. In fact, the canoes were full of warriors, who were lying flat on their faces. This was done to cover the Indian’s numbers and to make the English uncertain of any actual or imminent uprising (Meloche’s Account, MS.).

At the early hours of the day, a crowd of squaws, children, and warriors -some naked, and some others dressed in bizarre clothing- were found on the common behind the fort. They seemed restless and troubled. Many tall warriors, wrapped in blankets, were watched by the garrison as they covertly moved toward the fort. They returned a wicked glare up at the palisades and, then, with proud indifference they continued toward the gate. They were all admitted, because Gladwin showed some knowledge of Indian character and chose to prevail upon the Indians that their plan was detected and their hostility despised (Penn. Gaz. No. 1808). The whole garrison was ordered under arms as well as all English fur traders, who closed their storehouses and armed their men.

Pontiac, meanwhile, crossed with the canoes from the eastern shore and approached along the river road. Leading his sixty chiefs, they all moved with grave earnest. A Canadian settler, Louis Beaufait, was at the fort that morning and was on his way homeward when he reached the bridge that led over the stream, Parent’s Creek, where he saw the chiefs crossing from the farther bank. Beaufait stood aside to give them room to pass and as the last Indian passed, he recognized him as an old friend and associate. The Indian greeted him like usual and, for a second, opened the folds of his blanket to reveal a hidden gun. The Indian made a gesture toward the fort, indicating its purpose (This incident related by the son of Beaufait, to general Cass [See L. Cass, Discourse before the Michigan Historical Society, 30]).

By midmorning, Pontiac and his malcontent followers reached the fort and crowded the gateway. They were wrapped to the neck in colored blankets – some crested with hawk, eagle, or raven plumes; others with shaved heads leaving only the fluttering scalp-lock on the crown; while others wore long, black hair loosely on their backs or hanging about their brows like a wild stallion’s mane. Their faces were smeared with ochre and vermilion, white lead and soot. Their eyes hardened and menacing.

As Pontiac entered the gateway, he saw ranks of soldiers with their swords positioned on either side of the gateway. The black-skinned workers of the fur traders were also heavily armed and they stood in groups on the street corners. Then a measured tap on a drum marked an omen of misfortune. Pontiac immediately regained his composure and walked forward into the narrow street, his chiefs following in silence. Women and children looked out from the windows of their houses as Pontiac and his chiefs passed by on the street.

Pontiac and his chiefs reached the large building standing near the shore of the river, and they entered the council-house. Gladwin and several of his officers sat waiting for them, each with a sword by his side and a pair of pistols in their belts. Pontiac was uneasy but calmly demanded why there were so many men in the streets with guns. Gladwin replied through the interpreter, La Butte, that the soldiers were ordered under arms for discipline and exercise. This left Pontiac no other choice but to accept the untrustworthy situation and sit on the mats provided for them. The room was momentarily quiet, then Pontiac rose to speak. Holding the wampum belt in his hand and knowing this was the fatal signal for attack, Pontiac carefully addressed the commandant. He professed strong attachment to the English and declared he had come to smoke the pipe of peace and strengthen the chain of friendship. The British officers were alert and watched cautiously as Pontiac uttered his meaningless words, and they feared he may have realized his plot was discovered and that he would attack anyway (Carver, Travels, 159 [London, 1778]; M’Kenny, Tour to the Lakes, 130; Cass, Discourse, 32; Penn. Gaz. Nos. 1807, 1808; Pontiac MS; M’Dougal, MSS; Gouin’s Account; MS. Meloche’s Account; MS. St. Aubin’s Account, MS.).

At that moment, it was said Pontiac raised the wampum belt as if to give the signal of attack, but, also at that moment, Gladwin made a sign with a slight movement of his hand. A sudden clash of arms resonated from the outer passageway and a drum rolled a charge filling the council room. According the Gladwin’s letters, he and his officers remained seated. The commandant wished only to prevent the consummation of the plot and not to further increase an Indian fracture (Ibid.).

Pontiac was perplexed at what just happened. The room was momentarily quiet. Then Gladwin spoke. He assured the chiefs that friendship and protection would be extended to them as long as they continued to deserve it, but he would use ample vengeance for the first act of aggression. This ended the council; but, before leaving the room, Pontiac told the officers he would return in a few days with his squaws and children. He wanted to shake hands with their fathers the English. With this new piece of treachery, Gladwin made no reply. The gates of the fort were opened and the baffled Indians were authorized to depart (Ibid.).

Gladwin was reprehended by his superiors for not detaining the chiefs as hostages for the good conduct of their followers. Perhaps Gladwin feared if he was to arrest the chiefs at a public council, the act could be misinterpreted as cowardly and dishonorable. However, he was ignorant of the true nature of the Indian’s plot. And, yet, in his view, the entire affair was one of those common, impulsive outbreaks the Indians committed every now and then and it would eventually blow over.

The Indian differed from the European in the perception of military righteousness. In his view, to be cunning was wisdom. He honored the skills that could elude the adversary as well as the valor to subdue them. The object of war for the Indian was to destroy the enemy and, to accomplish this end, all means to do so were honorable. But to incur a needless risk would be folly, not bravery. Had Pontiac ordered his followers to attack the palisades of Detroit, not one follower would have obeyed. Pontiac may had been reverenced by them as a madman, but this decision would have ended his influence and fame as a war-chief.

Thwarted by his own treachery, Pontiac withdrew to his village. He was enraged and humiliated, yet, he remained resolved to persevere with his purpose. Gladwin’s actions at the fort caught him by surprise, and he thought it had to be either cowardice or ignorance from Gladwin. Thus, he decided it had to be ignorance because it seemed more probable. He would revisit the English again and convince them, if possible, that their suspicions against the Indians were unfounded. So, early the next morning, Pontiac returned to the fort with three of his chiefs. He carried in his hand the sacred pipe of peace, its stone-carved bowl, and its stem embellished with feathers. When they were finally given a meeting with the commandant, Pontiac addressed Gladwin and his officers: “My fathers, evil birds have sung lies in your ear. We that stand before you are friends of the English. We love them as our brothers. And to prove our love, we have come this day to smoke the pipe of peace.” Upon Pontiac’s departure, he gave the pipe to Captain Donald Campbell, second in command, as a pledge of his sincerity.

The afternoon on the same day, Pontiac called the young men of all the tribes to a game of ball, which played with great noise and shouting on the neighboring fields. At nightfall, the fort’s garrison were startled by sudden loud, shrill yells. The drums beat to arms and the troops were ordered to their posts. The alarming noise was found to have come from the winners in the ball game, celebrating with inharmonious loud shouts. Meanwhile, Pontiac was in the Pottawattamie village with the Wyandots consulting with the chiefs on another plot to ruin the English (Pontiac, MS.).

Early the next morning, the ninth of May, French inhabitants walked in procession to the settlement’s church near the river bank to attend mass, which was about half a mile above the fort. They returned to the fort before 11 o’clock without noticing any signs of an imminent attack from the Indians. Had they done so, they would have noticed the common behind the fort was filled with a large crowd of Indians from all four tribes. Pontiac advanced from among the crowd and approached the gate. The gate was closed. He was blocked from entry. Pontiac shouted to the sentinels and demanded why he was refused admittance. Gladwin himself responded that the great chief may enter, but the crowd he brought with him must remain outside. Pontiac said to Gladwin that he wished all his warriors to enjoy the fragrance of the friendly calumet (peace pipe). Gladwin’s answer was brief but courteous. He wanted none of Pontiac’s mob in the fort. Pontiac was rebuffed. He then dropped his masquerade and with a sneer of hate and rage, and turned abruptly from the gate. He walked towards his followers who were lying flat on the ground in multitudes just beyond the reach of gunshot (MS. Letter – Gladwin to Amherst, May 14. Pontiac MS., &c.).

Looking out from loopholes, the garrison saw the Indians running toward the house of an old English woman who lived with her family on a distant part of the common. The Indians beat down the doors and rushed inside. The next moment told the fate of the family from the familiar scalp yells. Another large body of Indians ran, yelling, to the river bank then leaping into their canoes and swiftly paddling to the Isle au Cochon, where an Englishman, named Fisher, lived and who was a former sergeant of the regulars. They dragged Fisher from his hiding place and murdered him, took his scalp, and loudly rejoiced over this trophy of brutal malice. The following day, several Canadians crossed over to the island to bury Fisher’s body.

Pontiac took no part in the savage deeds of his followers. His plan was defeated and he was in a terrible rage. He walked to his canoe along the shoreline and pushed it from the embankment. Pontiac thrusted the paddle into the water and vigorously stroked against the current towards the Ottawa village on the eastern shore. As he drew closer to the village, he shouted to the warriors but no men came to greet him, only the women, children, and old men. He pointed to the river and ordered all should prepare to quickly move camp to the western shore for safety, since the river would no longer mediate a barrier between the tribes and the English. The squaws promptly worked in obedience; gathering provisions, utensils, weapons, and even the bark that covered the lodges were carried to the shore, and, before evening, all was ready to embark.

By nightfall, nearly all the warriors returned to their village from their human hunting massacres. Still wearing his ghastly war paint, Pontiac entered the central area of the village brandishing his tomahawk and stamping on the ground, recounting former exploits and condemning vengeance against the English. The Indians gathered around him, and warrior after warrior caught the battle fever. Soon the center ring was crowded with dancers, circling round and round in a frantic pace with unearthly yells (Parent’s Account, MS.; Meloche’s Account, MS.).

After the war dance, the Indians began moving the boats to the western shore and by morning the transfer was complete. The whole Ottawa tribe crossed the river and pitched their wigwams on the western side, above the mouth of the little stream, Parent’s Creek — also known as Bushy Run then later known as Bloody Run for the fierce battle scenes between the Indians, the Royal Americans, and the Scottish Highlanders–(Gouin’s Account, MS.).

During the evening, more news of disaster reached the fort. A Canadian, named Desnoyers, came down the river in his birch canoe and landed at the water gate, bringing sad news of two British officers, Sir Robert Davers and Captain Robertson, who were ambushed and murdered by the Indians above Lake St. Clair (Penn. Gaz. Nos. 1807, 1808).

You have long ago heard of our pleasant Situation, but the Storm is blown over. Was it not very agreeable to hear every Day, of their cutting, carving, boiling and eating our Companions? To see every Day dead Bodies floating down the River, mangled and disfigured? But Britons, you know, never shrink; we always appeared gay, despite the Rascals. They boiled and eat Sir Robert Davers; and we are informed by Mr. Pauly, who escaped the other Day from one of the Stations surprised at the breaking out of the War, and commanded by himself, that he had seen an Indian have the Skin of Captain Robertson’s Arm for a Tobacco-Pouch!

Extract from an anonymous letter — Detroit, July 9, 1763

The Canadian added that Pontiac was joined by a formidable band of Ojibwas from the Bay of Saginaw (Pontiac MS.), and they were an especially savage tribe. Every Englishman in the fort, trader or soldier, was now ordered under arms. No man could lie down to sleep and Gladwin himself walked the ramparts throughout the night.

All was quiet until dawn. When the morning light rose from the east and the woods and fields became visible, a war whoop was heard on every side of the fort. The Indians came naked and yelled their unearthly whoops as they hurled themselves into an assault against the fort. The British soldiers hurried to their posts. This time it was not the Ottawas alone, but also the other tribes – Wyandots, Pottawattamies, and Ojibwas. There were bullets hitting hard and fast against the palisades. The Indians were filling their mouths with bullets for faster loading. And the soldiers were looking from their loopholes, expecting to see Indians gathering for a rush against their tenuous barrier, but there wasn’t much too see. Only commotion filled the air and guns firing. They were able to see Indians hiding behind barns and fences, some sneaking among the bushes, some lying flat in the hollows of the ground; while the others who found no shelter bounced about dodging shots from the fort. Not far from the fort, there was one low hill where countless black heads of Indians appeared and disappeared. Along its ridge, their guns were discharging white puffs of smoke as they carefully aimed at their intended targets – every fort loophole. The British soldiers, however, effectively responded with steady fire. And the Canadian engagés of the fur traders answered the Indian war-whoops with their own antagonistic outcries, while the English and provincials paid back the enemy with a volley of musket and rifle balls. Within half a gunshot of the palisades, there was a group of outbuildings where a host of Indians found shelter. A canon was quickly brought into position to discharge red-hot spikes upon them. They were soon wrapped in flames, forcing the Indians to flee in panic (Pontiac, MS.; Penn. Gaz. No. 1808; MS. Letter – Gladwin to Amherst, May 14, etc.).

For six hours the assault increased but as the day advanced, the Indians grew weary of their unsuccessful efforts. Their combativeness eventually lessened and died away, and the garrison was left in peace; however, from time to time, a solitary shot or a lone whoop was heard from a lingering Indian. The garrison had five wounded and the Indians a small loss.

Gladwin was convinced the whole affair was an enthusiastic show by the Indians and it would soon subside. Moreover, he felt they would be in great need of provisions and that he was resolved to open negotiations with the Indians. The interpreter, La Butte, who, like most of his countrymen, held a neutral position between the British and the Indians. He was sent to the camp of Pontiac to demand reasons for his conduct and to declare the commandant was ready to redress any real grievances. Two old Canadians of Detroit, Chapeton and Godefroy, also earnest to forward the negotiation, offered to accompany La Butte. The fort’s gates were opened for their departure as well as for others who wanted this opportunity to leave the fort. The others alleged motive to leave was that they did not want to experience the approaching slaughter of the British.

Reaching the Indian camp, Pontiac received the three Canadian ambassadors in a courteous manner. After La Butte delivered his message, his companions, Chapeton and Godefroy, worked to persuade the chief from pursuing his direction of hostile intentions. Pontiac patiently listened. With every proposal offered to him, Pontiac exclaimed his approval. But Pontiac was mindfully unmoved in his hostile position. He deliberately deceived the Canadians and the Canadians were too impetuous to accomplish their mission that they didn’t foresee the Indian’s game of manipulation. The Canadians were completely oblivious. La Butte then left behind Chapeton and Godefroy at the Indian camp to finish the conference and push the fancy benefits, while he returned to the fort.

Back at the fort, La Butte reported good news from his mission and added that peace could be had by offering the Indians presents. So when La Butte arrived back at the Indian camp, he was frustrated and upset to find his companions made no further progress in the negotiation. Pontiac continued to profess a strong desire for peace, but he evaded every positive proposal. The Indian chiefs withdrew to consult among themselves and shortly returned. Pontiac declared that they wished for a firm and lasting peace and, thus, they wanted to hold a council with their English fathers themselves. The Indians asked specifically for Captain Campbell, second in command, and he should come to their camp. The Indians expressed their confidence in him. The Canadians took their proposal and went back to the fort. They met with the commandant and put forth to him the Indian’s proposal for Captain Campbell. Gladwin was highly suspicious and he suspected treachery. But, Campbell wanted to comply with Pontiac’s request and he asked for Gladwin’s permission to go. Campbell insisted he felt no fear of the Indians and that he was always on friendly terms with them. Gladwin hesitated because of his suspicions but, finally, agreed to Campbell’s appeal. Campbell left the fort with a junior officer, Lieutenant M’Dougal, as well as with La Butte and several other Canadians.

Meanwhile, M. Gouin entered the Indian camp to learn what was happening. As he moved from lodge to lodge, he plainly heard and saw enough testimony that convinced him two British officers were advancing into the lion’s jaws (Gouin’s Account, MS.). He quickly sent two messengers to warn Campbell’s party that their safety was in peril. The messengers were breathless from running when they met up with the party. The warning came too late. Once embarked on their mission, the officers would not be diverted from it. They walked along the bridge and crossed over Parent’s Creek, and climbed the ground beyond when they saw before them the wide-ranging camp of the Ottawas.

A very large number of Indians gathered along the outskirts of the camp and as soon as they recognized the red uniform of the officers, they all raised a terrifying outcry of whoops and howls. It appeared as though the Indians’ reception was for captives taken in war; the women seized sticks, stones, and clubs and then ran toward Campbell and his companion as if to force them to pass the cruel ordeal of running the gauntlet.

When a party returned with prisoners, the whole population of the village turned out to receive them, armed with sticks, clubs, or even deadlier weapons. The captive was ordered to run to a given point, usually some conspicuous lodge, or a post driven into the ground, while his tormentors, arranging themselves in two rows, inflicted on him a merciless flagellation, which only ceased when he had reached the goal. Among the Iroquois, prisoners were led through the whole confederacy, undergoing this martyrdom at every village, and seldom escaping without the loss of a hand, a finger, or an eye. Sometimes the sufferer was made to dance and sing, for the better entertainment of the crowd.

The story of General Stark is well known. Being captured, in his youth, by the Indians, and told to run the gauntlet, he instantly knocked down the nearest warrior, snatched a club from his hands, and wielded it with such good will that no one dared approach him, and he reached the goal scot free, while his more timorous companion was nearly beaten to death.

Pontiac came forward. His voice calmed the unruly commotion. He shook the officers by the hand and then led the way through the camp. There was a puzzling collection of huts, mainly cone-shaped or half-spherical in shape, constructed of a thin framework and covered with rush mats or sheets of birch bark. Many birch canoes used by the Indians in the upper lakes were lying about among paddles, fish spears, and blackened kettles kept above the fire’s embers. The camp was also full of lean, wolfish dogs that howled endlessly at the strangers as they passed.

Pontiac paused at the entrance of a large lodge. He entered and pointed to several mats placed on the ground, opposite the entrance. The officers dutifully sat down. Instantly, the lodge was crowded with Indians. Most were chiefs and old men, and they too sat on the ground before the strangers. The remaining space was filled with a dense crowd that either stood or crouched, looking over each other’s shoulders.

When all was settled in the lodge, Pontiac spoke a few words. There was a brief pause that was broken by Campbell, who addressed the Indians in a short speech. There was complete silence. No reply. For a full hour, the officers looked at dark, mysterious faces that never wavered in their gaze upon them. There must have been no doubt at this point that Captain Campbell was aware of the danger in which he was placed. He decided to determine his true position. Campbell rose to his feet and declared his intention to return to the fort. Pontiac motioned to Campbell with his hand to remain seated and said to Campbell that he will sleep tonight in the lodges of his red children. Campbell and his companion were double-crossed and now in the hands of their enemies.

Many of the Indians were very eager to kill the captives on the spot, but Pontiac would not let his treachery be carried that far. He protected the two officers from injury and insult, and escorted them to the house of M. Meloche, near Parent’s Creek. The officers were given good quarters with limited liberty, the usual with safe custody (Meloche’s Account, MS.; Penn. Gaz. No. 1808; In a letter of James MacDonald, Detroit, July 12, the circumstances of the detention of the officers are related somewhat differently. Singularly enough, this letter of MacDonald is identical with a report of the events of the siege sent by Major Robert Rogers to Sir William Johnson, on the eighth of August. Rogers, who was not an eye-witness, appears to have borrowed the whole of his brother officer’s letter without acknowledgment).

By late evening, La Butte, the interpreter, returned to the fort. He was troubled and sad. His demeanor expressed the unhappiness of the news he was burdened to tell Gladwin and his officers. However, some of the officers suspected, without evidence, that La Butte was privy to the apprehension of the two ambassadors, and their accusation made matters worse for La Butte. He was depressed as it was, and the unfounded distrust toward him made him more moody, so he aimlessly drifted about the fort.

pontiac at the siege of detroit, 1763

The day after the officers were detained, Pontiac traveled with several of his chiefs to the Wyandot village. A part of the Wyandot tribe was influenced by Father Pothier, a Jesuit priest, and they refused to take up arms against the English. However, now they were being threatened with ruination if they continued to remain neutral. They were forced to submit and join the rest of their tribe. But they demanded one condition, and that was time to attend a mass before dancing the war-dance (Pontiac, MS.). Pontiac agreed.

After securing new allies, Pontiac began preparations to resume his operations by improving the arrangement of his forces. Some Pottawattamies were ordered to lie in wait along the river bank below the fort, while others concealed themselves in the woods so they could intercept any Englishman who would approach by land or water. Another band of the Pottawattamies concealed themselves nearby the fort and when no general attack was activated, they were to shoot down any exposed soldier or trader.

By the eleventh of May, Pontiac’s arrangements were completed. Several Canadians came to the fort early in the morning to offer friendly advice. Their message to the garrison was that the fort should be abandoned at once, since it will be stormed by 1500 Indians within the hour. Gladwin refused and the Canadians departed. Soon after, 600 Indians began a bombardment that continued until seven o’clock in the evening. Another Canadian appeared and brought a summons from Pontiac, demanding the surrender of the fort. Pontiac promised that the English would go unmolested on board their vessels, but they must leave all their arms and effects behind. Gladwin flatly refused (MS. Letter – James MacDonald to …, Detroit, July 12).

That evening, after Pontiac’s messenger left the fort, the officers met and considered what course of action this emergency required. According to one of the soldiers, the commandant was almost alone in the opinion that they ought to continue to defend the fort (Penn. Gaz. No. 1808). Whereas, the rest of the soldiers considered the only course of action that remained was to embark and sail for Niagara. Their situation appeared desperate. The fort only had enough provisions to sustain the garrison for three weeks, in which time there was little hope for help. The houses were made of wood and most thatched with straw, which would be set on fire by burning missiles. But what the officers feared most was that the enemy would make a general attack and cut or burn their way through the pickets, and resistance would be utterly useless. However, there was a Canadian in the fort who spent half his life among the Indians, and he assured the commandant that their primary rule of warfare was opposed to such maneuvers.

An Indian’s idea of military honor radically differed from a white man. His constant aim was to gain advantages without incurring loss. He set an immeasurable value to the lives of his own party, and he regarded victory as dearly purchased by the death of a single warrior. The war-chief attained his peak of fame when he boasted about the score of scalps he brought home without the loss of a man. And his reputation would be woefully diminished if the mournful wailings of the women mingled with the jubilant yells of the warriors. With all his logic and caution, the Indian was not a coward. His own way of fighting often showed extraordinary courage.

It was said, an Indian would sneak alone into the heart of an enemy’s country, and prowl about a hostile village watching every movement. Then, when night sets in, he would enter a lodge and calmly stir the decaying embers and, by its light, select his sleeping victims. With a cool deliberation, he would swiftly deliver a mortal thrust. He killed foe after foe, and tore off scalp after scalp until an alarm was given. Then, with a wild yell, he would leap into the darkness and be gone.

Time passed. There was no change and no relief for the harassed and endangered garrison. Day after day, the Indians continued to attack until their war cries and the rattle of their guns became familiar sounds. Weeks passed. No man would lie down to sleep, except in his clothes with his weapons by his side (MS. Letter from an officer at Detroit – no signature – July 31).

We have been besieged here two months, by Six Hundred Indians. We have been upon the Watch Night and Day, from the Commanding Officer to the lowest soldier, from the 8th of May, and have not had our Cloaths off, nor slept all night since it began; and shall continue so till we have a Reinforcement up. We then hope soon to give a good account of the Savages. Their Camp lies about a mile and a half from the Fort; and that’s the nearest they choose to come now. For the first two or three Days we were attacked by three of four Hundred of them, but we gave them so warm a Reception that now they don’t care for coming to see us, tho’ they now and then get behind a House or Garden, and fire at us about three or four Hundred yards’ distance. The Day before Yesterday, we killed a chief and three others, and wounded some more; yesterday went up with our Sloop, and battered their Cabins in such a Manner that they are glad to keep farther off.

Extract from a letter dated Detroit, July 6

Volunteer parties from the fort were dispatched to burn the outbuildings that sheltered the Indians. They cut down orchard trees and leveled fences until the ground around the fort was cleared and open. The Indians no longer had cover, it was an effective deterrent for keeping the Indians away from the fort. In addition, two vessels were employed on the river to sweep the northern and southern palisades with their gun fire. This also deterred the Indians from approaching and gave important aid to the garrison.

With all the obstacles the garrison put against the Indians, the Indians crawled their way through grass, sheltered behind every rising ground, and stealthily moved closer to the palisade. They shot arrows tipped with burning tow on the roofs of the houses, but the soldiers were ready with water from cisterns and tanks everywhere to douse the fires. The little church that stood by the palisade would have been especially vulnerable to fire had not the priest of the settlement threatened Pontiac with the Great Spirit’s vengeance should he be guilty of such an offense.

Pontiac was anxious to get possession of the garrison and he urged his warriors to apply more expedient tactics. Then Pontiac appealed to the French inhabitants to teach him the European method of attacking a fortified place using ordinary approaches, but the primitive Canadians said they knew little of such matters… and if some of them did know, they kept what they knew secret.

Soon after the first attack, Pontiac sent Gladwin a summons to surrender. He assured Gladwin that if the fort was given up at once, he would board his vessels with all his warriors. But if Gladwin persisted in defending the fort, Pontiac would treat him as he would treat other Indian enemies by burning him alive. Gladwin’s response was that he cared nothing for Pontiac’s threats (Pontiac, MS.). Pontiac renewed the battle with increased onslaughts. Eventually, Pontiac’s warriors were reinforced with 120 Ojibwa warriors from Grand River. Every man in the fort now slept on the ramparts, even during bad weather, as none were permitted to withdraw to their quarters (Penn. Gaz. No. 1808). Despite their circumstances, the wearied officers, soldiers, traders, and engagés maintained a spirit of confidence and cheerfulness even though they were getting weaker.

Great efforts were made to acquire more supplies of food. Every house was searched. Anything that would serve as food, even grease and tallow were collected and placed in the public storehouse. Compensation, of course, was first made to the owners. Even with all the precautions, Detroit would have been reluctantly abandoned or destroyed if it wasn’t for the providential assistance from several friendly Canadians and, especially, from M. Francois Baby, a popular resident who lived on the opposite side of the river. M. Francois Baby provided the garrison with cattle, hogs, and other supplies. These provisions were carried under the cover of night from his farm to the fort in boats, while the Indians were totally unaware of what was happening.

Since the Commencement of the Extraordinary Affair, I have been Informed, that many of the Inhabitants of this Place, seconded by some French Traders from Montreal, have made the Indians Believe that a French Army & Fleet were in the River St. Lawrence, and that Another Army would come from the Illinois; And that when I Published the cessation of Arms, they said it was a mere Invention of Mine, purposely Calculated to Keep the Indians Quiet, as We were Afraid of them; but they were not such Fools as to Believe me; Which, with a thousand other Lies, calculated to stir up Mischief, have Induced the Indians to take up Arms; And I dare say it will Appear ere long, that One Half of the Settlement merit a Gibbet, and the Other Half ought to be Decimated; Nevertheless, there is some Honest Men among them, to whom I am Infinitely Obliged; I mean, Sir, Monsieur Navarre, the two Babys, & my Interpreters, St. Martin & La Bute.

Extract from a MS. Letter – Major Gladwin to Sir J. Amherst; Detroit, July 8th, 1763

The Indians also suffered from hunger. Pontiac had no doubts that his warriors would have taken Fort Detroit in a single stroke, but, because of their typical imprudence, they neglected to properly provide for the necessities during a siege. Small parties were sent to visit the Canadian families along the river shore and, from house to house, they demanded food and threatened violence if the families refused. The food the Indians did obtain was wasted because of their usual carelessness. The Canadians could no longer endure the Indians reckless behavior, so, they appointed a delegation of 15 of the eldest among them to wait for Pontiac and complain about his followers’ conduct. The meeting was held at a Canadian house, most likely that of M. Meloche, where Pontiac made his headquarters and where the prisoners, Campbell and M’Dougal, were confined.

When Pontiac saw the delegation approaching along the river road, he grew very anxious to know the purpose of their visit. Pontiac desired for a long time to gain the Canadians as allies against the English. He made several advances toward that effect and he hoped that their present errand would be what he wanted to hear. After the Canadians arrived, they requested a meeting with the chiefs because they wished to speak about a matter of utmost importance. Pontiac immediately dispatched messengers to the different camps and villages. It wasn’t too long before the chiefs arrived. They entered the dwelling and seated themselves upon the floor after the formality of shaking hands with the Canadian delegates. The eldest of the French delegates stood and complained bitterly about the outrages the Indians committed.

You pretend to be friends of the French, and yet you plunder us of our hogs and cattle, you trample upon our fields of young corn, and when you enter our houses, you enter with tomahawk raised. When your French father comes from Montreal with his great army, he will hear of what you have done, and, instead of shaking hands with you as brethren, he will punish you as enemies.

Pontiac sat with his eyes to the ground, listening to every word spoken. When the speaker finished, he returned the following answer:

Brothers,