Armistice Day-1918–The Eleventh Hour on the eleventh day of the eleventh month; early morning at 6.30 a.m. – 11 November 1918 – when the American First and Second Army Headquarters heard the news of the Armistice signing to end the war, but the order was to continue fighting until the eleventh hour.

“I fired the battery on orders until 10.45, when I fired my last shot.“

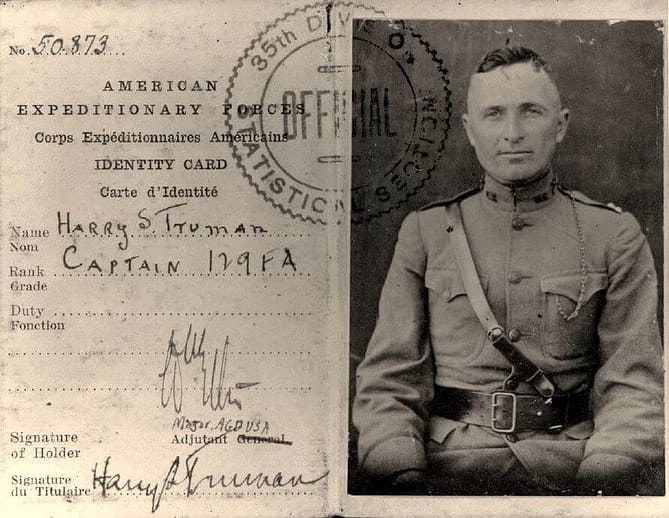

Captain Harry S. Truman‘s battery was East of Verdun, near the village of Hermeville. [pp.501]

- Post Contents -

ARMISTICE DAY-1918-THE ELEVENTH HOUR

Soldiers continued to fight as they waited for the eleventh hour. Then, finally, the watch-hands of time reached the eleventh hour. Across Europe’s bloodied battlefields, a silence rose marking the end of the costliest war in human history. [Ibid]

“Officers had their watches in their hands, and the troops waited with the same grave composure with which they had fought. At two minutes to eleven, opposite the South African brigade, at the eastern-most point reached by the British armies, a German machine-gunner, after firing off a belt without pause, was seen to stand up beside his weapon, take off his helmet, bow, and then walk slowly to the rear.

John Buchan, whose brother was killed in action two years earlier, continued:

“There came a second of expectant silence, and then a curious rippling sound, which observers far behind the front likened to the noise of a light wind. It was the sound of men cheering from the Vosges to the sea.” [Ibid]

An airman in Eddie Rickenbacker’s American air squadron cried out as he danced with joy: [Ibid]

“I’ve lived through the war!”

Another airman shouted very close to Rickenbacker’s ear:

“We won’t be shot at anymore!”

A company sergeant made the announcement to his men in the British 8th Division since their commanding officer was wounded in the head the night before:

“It’s all over, an armistice has been signed.”

Then one of his men asked, “What’s an armistice, mate?”

Another soldier replied, “Time to bury the dead.”

Final Victory

Marching into Mons, Lieutenant J.W. Muirhead saw three British corpses: [pp.502]

“…each wearing the medal ribbon of the 1914 Mons Star. They had been killed by machine gun fire that morning. As we got into Mons there were bodies of many of the enemy lying in the streets, also killed that day…Boys were kicking them in the gutter…The bells in the belfry were playing ‘Tipperary.’“

In North Wales, Robert Graves learned of the deaths of his two friends. His brother-in-law was killed two months prior. “The news of the armistice,” he later wrote, “sent me out walking alone along the dykes above the marshes of Rhuddlan (an ancient battlefield called the Flodden of Wales), cursing, and sobbing and thinking of the dead.” [Ibid]

London streets were filled with crowds rejoicing. They celebrated the armistice by drinking, singing, and dancing. Trafalgar Square was packed with a multitude of people as the news spread to villages and towns throughout Europe. [Ibid]

“I don’t know if I am glad or sorry to be alive. I only know that it wasn’t my fault that I am alive.”

Lieutenant-General Bernard Freyberg wrote to a friend in Britain on 18 November 1918. [pp.505]

American soldiers were shocked when they returned home to find how little their war exploits and successes were known in America. As Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur commander of the Rainbow Division the last weeks of the war, descended the gangplank of the converted German ocean liner Leviathan in New York on 25 April 1919, he was disappointed by the surprise that no dignitaries awaited his arrival. Only a young boy was present who asked him about the men. [pp.512]

Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur replied, “We are the famous 42nd.” The boy then asked the General if they had been in France. Sometime later MacArthur wrote, “Amid a silence that hurt with no one, not even children, to see us, we marched off the dock, to be scattered to the four winds — a sad, gloomy end of the Rainbow.” [Ibid]

Soldiers of the victorious armies celebrated with whatever they could get their hands on.

“Along in the evening, all the men in the French battery became intoxicated as a result of a load of wine which came up on the ammunition narrow gauge. Every single one of them had to march by my bed and salute and yell, ‘Vive President Wilson, Vive le capitaine d’artillerie americaine!’ No sleep all night. The infantry fired Very pistols, sent up all the flares they could lay their hands on, fired rifles, pistols, whatever else would make noise, all night long.” Captain Harry S. Truman [pp.503]

Armistice Day, 1918, left Austria without an Empire and Germany without an Emperor. [pp.505]

The Legend of the White Angel

Within two weeks of the battle of Mons on the Western Front in 1914, an angel appeared all in white riding a white horse with a flaming sword. It faced the advancing Germans, prohibiting their advancement. Due to endless marching and exhaustion, the Angel of Mons was not the only hallucination during the days of battle. ‘If any angels were seen on the retirement, as newspaper accounts said there were, they were seen that night.‘ [pp.58]

Private Frank Richards recalled the retreat from Le Cateau three days later.

“March, march, for hour after hour, without a halt; we were now breaking into the fifth day of continuous marching with practically no sleep in between.” [Ibid]

A soldier, Stevens, said, “There’s a fine castle there, see?” Pointing to a spot along the road. But nothing was there. “Very nearly everyone was seeing things, we were all so dead beat.” [Ibid]

Trench Warfare

American journalist E. Alexander Powell watched the Belgium troops move forward toward Weerde in 1914, then wrote what he saw. [pp.81]

“Back through the hedges, across the ditches, over the roadway came the Belgian infantry, crouching, stooping, running for their lives. Every now and then a soldier would stumble, as though he had stubbed his toe, and throw out his arms and fall headlong. A bullet had hit him. The road was sprinkled with silent forms in blue and green. The fields were sprinkled with them too. One man was hit as he struggled to get through a hedge and died standing, held upright by the thorny branches.’ A young Belgian officer ‘who had been recklessly exposing himself while trying to check the retreat of his men, suddenly spun around on his heels, like one of those wooden toys which the kerb vendors sell, and then crumpled up, as though all the bone and muscle had gone out of him.’ Nearby, a soldier ‘plunged into a half-filled ditch and lay there with his head under water. I could see the water slowly redden.‘” [Ibid]

German artilleryman, Herbert Sulzbach, wrote in his diary the first time he was in action as the German infantry captured the village of Premesque in 1914. [pp.93]

“We pull forward, get our first glimpse of this battlefield, and have to get used to the terrible scenes and impressions: corpses, corpses and more corpses, rubble, and the remains of villages. The bodies of friend and foe lie tumbled together. Heavy infantry fire drives us out of the position which we had taken up, and this is added to be increasingly heavy British artillery fire. We are now in an area of meadowland, covered with dead cattle and a few surviving, ownerless cows. The ruins of the village taken by assault are still smoking. Trenches hastily dug by the British are full of bodies. We get driven out of this position as well, by infantry and artillery fire.” [Ibid]

Sulzbach later that night wrote his thoughts of his first day in his diary.

“A dreadful night comes down on us. We have seen too many horrible things all at once, and the smell of the smoking ruins, the lowing of the deserted cattle and the rattle of machine-gun fire makes a very strong impression on us, barely twenty years old as we are, but these things also harden us up for what is going to come. We certainly did not want this war! We are only defending ourselves and our Germany against a world of enemies who have banded together against us.” [Ibid]

The front line that winter in the British sector had 20,000 men suffering with ‘trench feet’. British Commander-in-Chief, Sir John French, found the ground ‘only a quagmire’, but General Smith-Dorrien later recalled his experience. [pp.114]

“In that part of the world, there appeared to be no stones or gravel, and rain converted the soil into a sort of liquid mud of the consistency of thick porridge without the valuable sustaining quality of that excellent Scots mixture. To walk off the roads meant sinking in at once.‘ As the protective parapets were built ‘they gradually subsided and the trenches filed with water, so to retain any cover at all meant constant work’.” [Ibid]

A German counter-attack at Givenchy on 20 December 1914 regained the few saps (narrow trenches that extended forward from a main trench line, often only a few yards from an enemy trench, and were frequent locations of brutal hand-to-hand fighting) that were taken two days earlier. Weather was another source of danger. The Official History of the Indian Corps in France stated the following: [pp.115]

“The elements were warring on the side of the enemy, for torrential rain during the night had made the trenches almost untenable. In many places the fire-step had been washed away, and the men were consequently unable to stand high enough to fire over the parapet. The trenches were knee-deep and in some places waist deep in mud and icy water, which clogged a large number of rifles and rendered them useless. The thick and holding mud made the trenches veritable death-traps. Men had their boots, and even their clothes, pulled off by the mud.” [Ibid]

Other Battlefields

Lieutenant Colonel Winston Churchill, on 22 December 1914, told his Admiralty officials that Sir John French ordered ‘instant fire’ on any German white flag on the Western Front. [pp.117]

“Experience having shown that the Germans habitually and systematically abuse that emblem. Any white flag hoisted by a German ship is to be fired on as a matter of principle. An obviously helpless ship would be allowed to surrender but in cases of doubt the ship should be sunk. White flags should be fired upon with promptitude.” [Ibid]

A British officer, Lieutenant G.V. Carey, present at Hooge – east of Ypres in Flanders in Belgium on the Eastern Front – when the attack began on 29 July 1915. [pp.178]

“This was the most alarming frightfulness that our fellows had as yet knocked up against. Apart from the number of people it had blown to bits the explosions were so terrific that anyone within a hundred yards’ radius was liable to lose his reason after a few hours, and the 7th battalion had had to send down the line several men in a state of gibbering helplessness.” [Ibid]

On 30 July 1915, the Germans used flamethrowers for the first time in the attack from Zouave Wood to Hooge Crater, sending jets of burning petrol against their enemy.

“There was a sudden hissing sound, and a bright crimson glare over the crater turned the whole scene red. As I looked I saw three or four distinct jets of flame – like a line of powerful fire-hoses spraying fire instead of water – shoot across my fire trench.‘ The men caught in the blast of the fire ‘were never seen again‘.” Lieutenant Carey [Ibid]

“I was really lucky to escape with my life yesterday, because the Cossacks show no mercy if they catch you! I and a patrol were ambushed in the endless forest and swamp hereabouts. We lost more than half our men. Hand-to-hand fighting, with all of us thinking our last hour had come. It was pure chance that two or three of us got away, me last because my horse is weak and, to crown it all, went lame!!!! Then a life-to-death chase with the first the brutes only ten paces behind me, firing all the time and shrieking ‘Urrah-Urrah’. I kept feeling his lance in my liver. I used my sabre to flog my horse to its limits and just made it back to my unit. You should see how they respect me!” [pp.179]

Oskar Kokoschka – Austrian painter-turned-cavalryman – wrote a letter to a friend from the Galician Front describing what happened to him on 5 August 1915. [Ibid]

1918 – Cantigny village was under American control. One after another, seven German counterattacks occurred within 72 hours. The battle continued killing 200 American soldiers and caused another 200 Americans useless by German gas attacks. The strain of continuous shelling and fatigue for three days of intense action, the men were exhausted. One American lieutenant started shooting wildly at his fellow soldiers until he was killed by a German shell. According to Commander, Colonel Hanson E. Ely, he described the men as ‘half crazy, temporarily insane’. When relief finally arrived, Colonel Hanson Ely recalled, ‘They could only stagger back, hollow-eyed with sunken cheeks, and if one stopped for a moment he would fall asleep.’ The Americans held Cantigny. [pp.426-427]

On 11 September 1918, the Americans began their final preparations to drive the Germans out of the St Mihiel Salient. The battle was expected to be fierce. Lieutenant-Colonel, George S. Patton, Jr., informed his men: ‘American tanks do not surrender so long as one tank is able to go forward. It’s presence will save the lives of hundreds of infantry and kill many Germans.‘ [pp.458]

THAT CHRISTMAS DAY | 1914

An early darkness rose that Christmas Eve along the front lines, and in some sections there was that moment of peaceable behavior among men.

“We got into conversation with the Germans who were anxious to arrange an Armistice during Xmas. A scout named F. Murker went out and met a German Patrol and was given a glass of whiskey and some cigars, and a message was sent back saying that if we didn’t fire at them they would not fire at us.“

Sir Edward Hulse, 25-year-old lieutenant with the Scots Guard – battalion war diary [pp.117]

At morning, German soldiers approached the British wire. The British soldiers went to meet them.

“They appeared to be most amicable and exchanged Souvenirs, cap stars, Badges, etc.”

Sir Edward Hulse [Ibid]

The British offered plum puddings to the German soldiers.

“…which they much appreciated.”

Sir Edward Hulse [Ibid]

Both sides agreed to bury the British dead who were killed and defeated during the December 18th night raid. The British corpses still lay between the lines, most at the German front-line wire.

“The Germans brought the bodies to a half way line and we buried them. Detachments of British and Germans formed a line and a German and English Chaplain read some prayers alternately. The whole of this was done in great solemnity and reverence.”

Sir Edward Hulse [Ibid]

That Christmas Day, fellowship between the Germans and their enemies happened most everywhere in the British ‘No-Man’s Land’, including places along the French and Belgian lines. Almost always the contact between enemy lines was initiated by the German troops, through messages or song. Near Ploegsteert, a British officer who spoke German, Captain R.J. Armes, listened with his men to a German soldier’s serenade. His men called for another song and the German responded with Schumann’s ‘The Two Grenadiers’. Men from both sides left their trenches and met each other in the No-Man’s Land. “There was some conviviality,” as Captain R.J. Armes remembered it. There were two final songs, “Die Wacht Am Rhein’ from the Germans and ‘Christians Wake!’ from the British. [pp.118]

“Most peculiar Christmas I’ve ever spent and ever likely to. One could hardly believe the happenings.“

Sapper J. Davey on the Western Front wrote in his diary. He exchanged souvenirs with the Germans in the trenches across from them. [Ibid]

Some British soldiers joined fellow German infantrymen in chasing hares, while some played with a football in No-Man’s Land. R.D. Gillespie, a 2nd Lieutenant British officer, was invited into German lines and shown a board that honored a British officer who reached their trench in a previous attack before he was killed. [Ibid]

“…joined the throng about half-way across to the German trenches. It all felt most curious: here were these sausage eating wretches, who had elected to start this infernal European fracas, and in so doing had brought us all into the same muddy pickle as themselves.“

Bruce Bairnsfather – author of the book about trench tales ‘Bullets & Billets’. He recalled going into No-Man’s Land on that Christmas Day. [Ibid]

“There was not an atom of hate on either side that day; and yet, on our side, not for a moment was the will to war and the will to beat them relaxed.“

Bruce Bairnsfather – his first close-up of German soldiers. [Ibid]

“I think I have seen one of the most extraordinary sights today that anyone has ever seen. About 10 o’clock this morning I was peeping over the parapet when I saw a German, waving his arms, and presently two of them got out of their trenches and some came towards ours. We were just going to fire on them when we saw they had no rifles so one of our men went out to meet them and in about two minutes the ground between the two lines of trenches was swarming with men and officers of both sides, shaking hands and wishing each other a happy Christmas.“

Second Lieutenant Dougan Chater – in a letter to his mother from his trench near Armentieres. [Ibid]

“For the rest of the day nobody has fired a shot and the men have been wandering about at will on the top of the parapet and carrying straw and firewood about in the open. We have also had joint burial parties for some dead – some German and some ours – who were lying out between the lines.“

Second Lieutenant Dougan Chater – continued in his letter to his mother. [Ibid]

The French Foreign Legion also participated in a part of the line where the fighting stopped. Burial parties went to work, and cigars and chocolate were exchanged. [pp.119]

“No shooting was interchanged all day, and last night absolute stillness, though we were warned to be on the alert. This morning Nedim, a picturesque, childish Turk, began again standing on the trenches and yelling at the opposite side. Vesoncsoledose, a cautious Portuguese, warned him not to expose himself so, and since he spoke German made a few remarks showing his head. He turned to get down and – fell! a bullet having entered the back of his skull: groans, a puddle of blood.” [Ibid]

Victor Chapman, an American and Harvard graduate of 1913, was among the Legionnaires who wrote about his experience to his parents.

Ten years later, Winston Churchill, remarked on victory:

“Every Allied nation shared them. Every victorious capital or city in the five continents reproduced in its own fashion the scenes and sounds of London. These hours were brief, their memory fleeting; they passed as suddenly as they had begun. Too much blood had been spilt. Too much life-essence had been consumed. The gaps in every home were too wide and empty. The shock of an awakening and the sense of disillusion followed swiftly upon the poor rejoicings with which hundreds of millions saluted the achievement of their hearts’ desire. There still remained the satisfactions of safety assured, of peace restored, of honour preserved, of the comforts of fruitful industry, of the homecoming of the soldiers; but these were in the background’ and with them all there mingled the ache for those who would never come home.” [pp.503]

Aftermath, March 1919

by Siegfried Sassoon

Have you forgotten yet?

Look down, and swear by the slain of the War that you’ll never forget.

Do you remember the dark months you held the sector at Mametz –

The nights you watched and wired and dug and piled sandbags on parapets?

Do you remember the rats; and the stench

Of corpses rotting in front of the front-line trench –

And dawn coming, dirty-white, and chill with a hopeless rain?

Do you ever stop and ask, ‘Is it all going to happen again?’

Do you remember that hour of din before the attack –

And the anger, the blind compassion that seized and shook you then

As you peered at the doomed and haggard faces of your men?

Do you remember the stretcher-cases lurching back

With dying eyes and lolling heads – those ashen-grey

Masks of the lads who once were keen and kind and gay?

Have you forgotten yet? …

Look up, and swear by the green of the spring that you’ll never forget.

References

Gilbert, M. 1994. The First World War: A Complete History. Henry Holt and Company, Inc.

Updated 2020