- Post Contents -

Indian Fur Trade and the albany congress

In eighteenth century North America, domination of its western land was the primary reason for the competition between Great Britain and France, but it was the fur trade in the Great Lakes region that both nations wanted, including a fur trade commerce monopoly with the Indians. Warfare was inevitable.

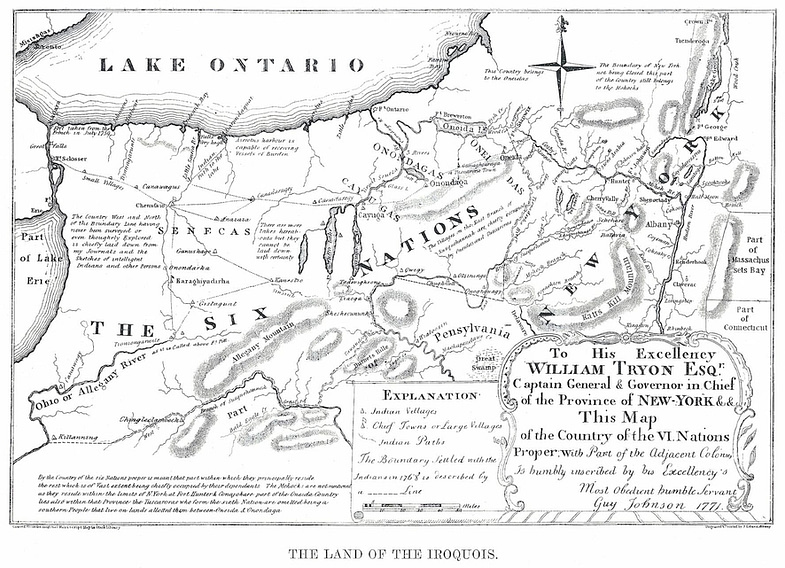

The Iroquois, however, controlled the fur trade in the Great Lakes region and they dominated the interior exchanges. They received furs from western Indians and exchanged them in Albany for British goods. But in Albany, the Indian Commissioners were Dutch traders and they supervised the exchanges. These Indian Commissioners had basic oversight of Indian affairs in the province of New York but they were corrupt, and British interests and Indian satisfaction were secondary to their own desire for profit.

These New York Indian Commissioners needed to keep Albany as the center of exchange, so they deliberately restrained other New Yorkers bartering rights to trade with the interior Indians. However, their rules did not apply to citizens from other colonies and, by 1730, British traders gradually increased in the West (P. Wraxall, An Abridgement of the Indian Affairs, xvi).

The French were growing suspicious of the British because they were originally in the St. Lawrence Basin region before them. They discovered the British offered higher prices to the Indians for their furs and supplied the Indians with superior merchandise. The French realized their commerce with the Indians declined, while the British commerce with the Indians increased (L.H. Gipson, The British Empire before the American Revolution, V, 62-63). So the French left the Saint Lawrence Basin fur trade with the Huron and Ottawa Indians and went westward. They quickly developed a direct exchange with the western Indians.

The French established numerous forts and trade posts and conducted a profitable business with the Indians. The British colonists soon settled in the region and were threatening the French trading monopoly with the Indians. The French increased their trading stations, but their trade continued to decline. The British had the competitive advantage but the British traders multiplied.

Both France and Great Britain claimed the Ohio Valley region as their own. Great Britain had the region included in their sea-to-sea charters that were granted to their settlements, and France declared their right to the region on the explorations of La Salle, who had proclaimed a French title to the Mississippi Basin as well as to the lands drained by its tributaries (G. Wrong, The Rise and Fall of New France, II, 743-744).

In 1749, Quebec’s governor sent Céloron de Bienville, a captain in the colony’s troops, to the Ohio Valley. From his journey, he proclaimed French title to the region west of the Allegheny Mountains and warned all Englishmen to vacate the territory. The French then forced the British traders with armed threats to leave the West.

When news of the British ejection from the Ohio Valley reached Virginia’s Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie, he dispatched George Washington, a young officer in the provincial militia, to make inquiries. Washington left the colony in the fall of 1753 and arrived at the French outpost, Fort LeBoeuf, in December. There the French firmly informed Washington that Marquis Duquesne sent strict orders to occupy the entire Ohio River Valley. Washington rode back to Virginia with the French reply (Wrong, op., cit., II, 749-750). The line was drawn – the British had to fight or withdraw.

Virginia’s response to the French was to send a group of settlers through Britain’s chartered Ohio Company as well as soldiers to build a fort at the fork of the Ohio – near the present site of Pittsburgh. On 17 April 1754, the French attacked the fort and it surrendered. Washington rushed to reinforce the fort’s position but met defeat on 3 July 1754. Washington quickly retreated to Virginia, abandoning the Ohio Valley to the French.

Iroquois Confederacy and the lords of trade

Escalation of the French and British rivalry in the Ohio Valley weakened the alliance between the Iroquois Confederation and the British colonies. And the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 reminded the French that the Iroquois Confederacy was still a British subject. But despite this alliance, the French maintained a respect with some of the Six Nations tribes and their largest favor came from the Indian nations nearest Canada -Cayugas and Senecas- whereas the smallest favor came from the Mohawks.

However, the Six Nations feared the French expansion less than they did with the British expansion because the French welcomed the Indians to dwell among them, whereas, the British settlers discouraged Indian dwellers within their settlements.

Another troublesome situation was the settlers who grabbed land by fraudulent means for personal expansion. These settlers would either seize land without a pretext of a formal purchase, or they would steal a sale by closing it after the Indians became too intoxicated to stop them. These thieves would also negotiate legitimate deed sales, but would deceptively extend more land than the Indians had included to the deed. Such corruption alienated the Six Nations to befriend the French and, most likely, allow French influence within their Indian councils. However, the Six Nations also deliberately engaged in politics to devise ways to keep the rivalry between the British and the French off balance (Gipson, op., cit., V, 108).

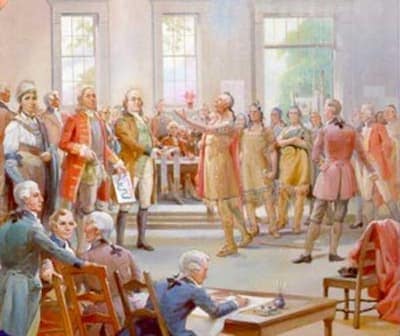

In 1751, New York’s Governor George Clinton recognized the seriousness of the Indian situation and invited all provinces to meet with the Six Nations in Albany. However, only Massachusetts, Connecticut, and South Carolina joined New York, which resulted in a plea to the Indians to remain loyal (Edmund B. O’Callaghan, ed., Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York, VI, 717-726). After the meeting, it was noted that their mere urgings would not keep the Iroquois friendly.

Thus, New York Governor George Clinton addressed the Lords of Trade:

Without directions and instructions of a different nature from hitherto given, no Govr in my opinion, has in his power to do what is requisite for preserving the fidelity of the Indians … [and] that some method must be speedily thought on to secure the Colonies against the designs of the French.

Governor Clinton to the Lords of Trade, 1 October 1751; O’Callaghan Documents, VI, 738

Two years after, a Mohawk delegation, though friendly, went to Governor Clinton and complained through their spokesman, Hendrik Peters, about British trespassing on their ancestral lands which threatened to overwhelm their villages. They accused the colonies of leaving them defenseless against French attacks. Then the Mohawks told their spokesman that they ended their century-old covenant with the provinces:

So Brother you are not to expect to hear of me any more, and Brother we desire to hear no more of you.

Edmund B. O’Callaghan, ed., Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York, VI, 738

It became clear to the British government that their disunity in the colonies was an issue that discouraged Mohawk influence and services from being available. They were now in a perplexing situation and vulnerable to imminent French attacks. Virginia’s Governor Dinwiddie sent alarming information to Governor Clinton about French armed movements in the Ohio Valley. Governor Clinton became gravely concerned. He rushed to notify the Lords of Trade about the dangerous turn of events … and the Lords turned around and warned the Earl of Holdernesse (one of His Majesty’s principal secretaries of state, Robert Darcy, fourth and last Earl of Holdernesse who served as Secretary of State for the Southern Dept. and the colonies until 23 March 1754, after which he became Secretary of State for the Northern Dept.) of unchecked French aggression in the Ohio Valley and its dangerous implication for Britain’s western expansion.

Governor Dinwiddie continued to send reports to the Earl of Holdernesse warning him about French movements. In August 1753, Holdernesse received authorization from the Cabinet Council to send out his letter to all the colonies cautioning them to assist each other in case of attack (O’Callaghan, Documents, VI, 794-795; Gipson, op. cit., IV, 289). Unfortunately, few provinces heeded Holdernesse’s advice, although they did promise aid. Ultimately, little help was offered to the Virginia colony when it sought to remove the French from the Ohio Valley.

On 18 September 1753, the Lords of Trade requested Sir Danvers Osborne (successor to Governor Clinton of New York) to summon an Indian conference. The colonies invited to join the New York meeting were Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. But the Lords of Trade were not convinced that the Iroquois’ hesitancy to commit to the British would seriously affect the security of the remaining colonies; those not invited were Rhode Island, Connecticut, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Delaware (Lords of Trade to Sir Danvers Osborne, 18 September 1753 [Ibid, VI, 800-801]).

However, two days after Governor Osborne assumed the N.Y. Governor’s office in October 1753, he committed suicide. He was replaced by Lieutenant Governor James Delancey as acting Governor.

England and America recognized that a union of colonies were necessary. Colonial authorities wanted a union of the colonies but not a political federation. They wanted military efficiency and the union would make each colony obliged to contribute to a specific quota of men (N.Y. Col. Doc. VI William Shirley [Gov. of Massachusetts] to Earl of Holdernesse [Sec. of State in charge of colonial affairs], 7 Jan. 1754; Am. and W.I. 67).

Letters of invitation from the Lords were finally sent and Delancey decided to hold the conference in Albany on 14 June 1754. In another letter to other primary officials, Delancey indicated that the King wanted all colonies united under one general treaty with the Indians. He urged that the colonial delegates be given power to authorize construction of forts to protect the Indians (Delancey to Lords of Trade 22 April 1754 [O’Callaghan, Documents, VI, 833-834]).

Convinced by Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts, Delancey requested Rhode Island and Connecticut to attend the Albany Congress along with the colonies already invited by the Lords of Trade. Governor Shirley hoped that the conference would unify these provinces and the more colonies represented the better. Shirley recommended to the attending governors that they instruct their commissioners to work for union (Delancey to Shirley 5 March 1754 [Archives of Massachusetts, IV, Colonial, 1721-1773, 443]).

The decision that was needed to manage the uncertainty of French attacks and the Iroquois alliance had to come from colonial cooperation. Governor Shirley strongly emphasized the importance of union and insisted the conference be held in Albany. Shirley became the first colonial statesman to seize the occasion presented by the Albany Congress to try and form a coalition, which became more essential every day.

Unfortunately, the Albany Congress was unable to appease the Indians or provide a joint management of Indian affairs to strengthen the frontiers. These were the chief objectives for the British government. So the Board of Trade blamed the Albany Congress for their failure to have these matters regulated, which created a serious situation from the mismanagement of Indian affairs. Especially when the Albany commissioners unanimously agreed that the Indian affairs should be under one common administrator supported by the general expense of all the colonies.

The need for a confederation

The need for a confederation was not new, since it existed at the founding of the colonial provinces. The early settlers feared attacks from the French and the Dutch, as well as from the Indians. As a result, they gathered together to confront such threats. These settlers held intercolonial conferences and offered numerous proposals for a union, which eventually established a United Colonies of New England. The United Colonies were Massachusetts, Plymouth, New Haven, and Connecticut. This New England Confederation marked a beginning of a union, but it lacked the strength to enforce a successful defense league against the threats and onslaughts from the Dutch, French, and Indians.

Two Representatives were designated from each government, and without their unanimous consent no other colony could join nor could any two members unify to form a domination. The commissioners were given adequate power for defense, but were limited in power for offensive operations. They could settle disputes among members and govern Indian affairs. The representatives had a right to explain the Articles of the Confederation but, truth be told, only the General Courts could give the absolute interpretation. Ultimately, they could not execute orders because they lacked enforcement and all they could do was render their decisions in the form of advice to the colonies (Herbert Osgood, The American Colonies in the Seventeenth Century, 1, 401).

Constitutionally, the Confederation was an organization not governed by law. It was denied actual power because of reservations by the member governments, but functioned as a joint standing committee of the legislatures. It also demonstrated the need for a cooperative force to conquer external danger, and it embodied the only true achievement for a voluntary federation in all of pre-Revolutionary history.

French encroachment in the Ohio Valley and their endangerment to the British settlers in the Ohio Valley and eastward, caused the Anglo-Iroquois alliance – Six Nations of the Iroquois – an uneasiness as to the stability of colonial cooperation and defense. Virginia tried to resist but the other colonies failed to assist, leaving Virginia helpless. And because of the renewed threat to security, colonial leaders hastily reconsidered their need for a union. Among those offering proposals for a union was Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania. In 1750, Franklin had already pressed the importance for settlement protection with a colony confederation as well as the value of maintenance with the Indian alliance. Franklin supported an association of volunteers, which would consist of a Grand Council that represented the colonies, including the President General appointed by the King. Taxes paid into the general treasury would decide council delegates.

Aside from Franklin and Archibald Kennedy (the Kings Receiver General at New York), Lt. Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia drafted his own recommendations for the consolidation of the colonies. He advised the colonies be divided into two divisions of north and south in order to operate together for defense and to preserve the Indian alliance (Writings of Benjamin Franklin, III, 40-45). Yet, in spite of all the good suggestions, the colonial provinces failed to agree on a common plan of action against the French or unify.

Interference from the French increased, while Indian relations grew worse. The Lords of Trade understood the seriousness of the situation and they summoned an intercolonial congress to appease Iroquois grievances by rebuilding their Anglo-Iroquois Alliance. The Lords of Trade focused only on this important situation and did not add the problem of a colonial union.

For my own part I cannot help thinking that unless there be a united and vigorous opposition of the English Colonies to them, the French are laying a solid foundation for being, some time or other, sole masters of this continent; notwithstanding our present superiority to them, in points of numbers. But this union is hardly to be expected to be brought about by a confederacy or voluntary agreement, among ourselves. The jealousies the colonies have of each other … will effectually hinder any thing of this kind from taking place … we should never agree about the form of the union or who should have the execution of the articles of it … it will never be taken, unless we are forced to it by the supreme authority of the nation.

Doctor William Clarke to Benjamin Franklin; 6 May 1754 (Massachusetts Historical Society Collections, IV, 74-75)

It was not the Lords of Trade but Massachusetts Governor Shirley and Benjamin Franklin who were the original movers in creating a discussion regarding union at Albany. Governor Shirley considered the meeting an excellent opportunity to merge the colonies. He expressed this thought in a communication to the Massachusetts General Court:

Such a Union of Councils … may lay a foundation for a general one among all His Majesty’s Colonies, for the mutual Support and Defence against the present dangerous Enterprizes of the French on every Side of them.

William Shirley, Correspondence of William Shirley, Governor of Massachusetts and Military Commander in America, 1731-1760, Charles Lincoln, ed. II, 44.

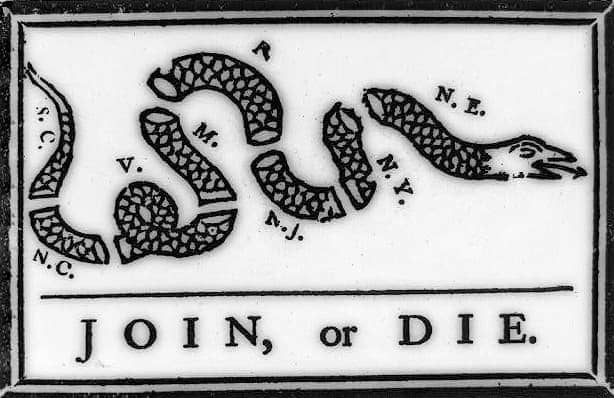

Three days after William Clarke’s letter, Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette made an appeal to the public for a collaborative colonial action. It highlighted France’s confidence in their ability to successfully invade British territory because of the disunited state of governments.

A graphic design of a snake cut into eight pieces symbolized the Gazette’s appeal for a collaborative colonial action. The head was New England – and each of the other seven parts marked a province: New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. There was no reference to Georgia or Delaware. Georgia may have been excluded because of its defenseless frontier and any contribution would have been useless to common security. Delaware, however, shared Pennsylvania’s governor and was most likely considered as a part of a set with Pennsylvania.

Underneath the snake it read: JOIN, OR DIE. (Pennsylvania Gazette, 9 May 1754). The words were clear: either the colonies joined together in defense or their safety was in grave danger. Other newspapers reproduced the snake graphic in similar form, which gave it an extensive circulation to dramatically portray such an important message for a union. (The snake graphic appeared in these newspapers: New York Gazette, 13 May 1754; New York Mercury, 13 May 1754; and the Boston Gazette, 12 May 1754 [Albert Mathews, The Snake Devices, 1754-1776 and the Constitutional Courant, 1765 – Colonial Society of Massachusetts, XI, 409-453].)

Benjamin Franklin also wrote Short Hints Towards a Scheme for Uniting the Northern Colonies. He no longer supported a voluntary federation, but suggested a provision for a Grand Council presided by a military officer called the Governor General – whom the King would appoint and support. The Governor General would have power to veto the acts of the council (Franklin Writings, II, 197-199). His piece also called for the establishment of a defensive association of the colonies in an effort to check the French and retain the loyalty of the Indians. He knew, as did Archibald Kennedy of New York, how close the connection was to French danger, Indian affairs, and the colonial union (Archibald Kennedy, Serious Considerations on the Present State of the Northern Colonies, 6ff).

Franklin’s strategy was regarded as the most developed plan of union designed at that time. He offered an actual system of substantial power for a central government to legitimately tax. It was a type of balanced agency that would determine the number of delegates each colony would have in the Grand Council, while keeping a subordinate role for the mother country. The power to veto laws was given to the Governor General – the King’s appointee. Franklin hoped the Albany Congress would step up and be the opportunity needed to establish the union.

Before Franklin submitted his ideas before the commissioners for consideration, he sought advice from James Alexander, a local government councillor from New York (8 June 1754). Alexander assumed military men would be the qualified member for the Council and he expressed his skepticism to Franklin that the provinces would find citizens inadequately skilled for such membership. Alexander also feared some councillors could reveal defense plans that were debated in the Council, and he recommended the association select a special committee -formerly known as the Council of State- with a few good men to know all matters before presenting them to the Grand Council (James Alexander to Cadwallader Colden, 9 June 1754 [Franklin, Writings, III, 199-200]).

Alexander cautioned it would be best that the central government have the right to increase but not decrease parliamentary duties that affected the colonies, and that military security must be improved. When Alexander completed his analysis of Franklin’s Short Hints, he sent it to a fellow councillor, Cadwallader Colden, Chief Lieutenant of ex-Governor Clinton.

Colden agreed for the need of a defensive union but advised the government would need to appeal to Parliament to secure the necessary operating revenue. Colden also questioned the structure of the council. Was it to be legislative or executive? If executive, he had a constitutional objection that no elective body should retain executive functions. He also found fault with the provision for fixed sessions of the Grand Council, since neither the Privy Council nor Parliament itself had such privilege. Colden did object to some sections in Short Hints, but, for some reason, he neglected to mention the most obvious point that the congress had a singular goal which was to discuss Indian affairs (Colden dispatched to Franklin, 20 June 1754, his comments and Alexander’s on Short Hints).

Franklin’s “Short Hints”: To order all Indian Treaties Committee’s to hold or order all Indian Treaties, regulate all Indian Trade, make Peace and Declare War with Indian Nations.

Albany Plan: That the President General, with the Advice of the Grand Council, hold or Direct all Indian Treaties in which the General Interest or Welfare of the Colony’s may be Concerned; and make Peace or Declare War with Indian Nations.

Trumbull Short Plan: That the President General with the Advice and Consent of the Grand Council hold and Direct all Indian Treaties in which the General Interest or Welfare of These Colonies may be concerned; and make Peace or Declare War with Indian Nations.

Trumbull Long Plan: That the President General with the Grand Council Summoned and Assembled for that Purpose, or a Quorum of Them as aforesaid shall hold and direct all Indian Treaties in which the General Interest or Welfare of these Colonies may be Concerned; and make Peace or Declare War with Indian Nations.

Later additions, below, were not found in the list above. These changes strongly suggested the documents were composed in this order. The alterations appeared to be a conscious effort to soften the implications of wording adopted by a broader member group.

Franklin’s “Short Hints”: Make all Indian purchases not within proprietary Grants. Committees make all Indian Purchases of Lands not within the Bounds of Perticuler Colonies.

Albany Plan: That they Make all Purchases from the Indians for the Crown, of Lands now not within the Bounds of Particular Colonies or that shall not be within their Bounds when some of them are reduced to more Convenient Dimensions.

Trumbull Short Plan: That They make all purchases from Indians for the Crown of Lands not now within the Bounds of particular Colonies, or That shall not be within Their Bounds when the Dimention [written directly upon the first five letters of this last word is: Exten, making it read Extention] of Some of Them are rendered more Certain.

Trumbull Long Plan: That they make all purchases from Indians for the Crown of Lands not now within the Bounds of particular Colonies, or That shall not be within their bounds when the Extention of Some of them are rendered more Certain.

These differences appeared as conclusive evidence that the two documents in Trumbull’s hand were composed and revised after the Albany Plan was approved by the Congress. Both content and wording appear to be later modifications, not sources, of the Albany Plan. It is also noted that its details are contrary to what Franklin advocated, and it’s certain that he had nothing to do with their composition.

…immediate directions will be given for promoting the plan of a general concert between his Majesty’s colonies, in order to prevent or remove any encroachment upon the dominion of the crown of Great Britain.

Thomas Robinson to Governor Shirley, 21 June 1754; endorsing measures taken with reference to the Albany Congress

The Albany Plan was originally based on Franklin’s Short Hints, but apparently it was modified and altered in several items according to some other delegates – most likely included Thomas Hutchinson (last royal governor of Massachusetts Bay) – to gain support of a majority. It was finally cast in final form once again by Franklin.

failure to adopt a plan of union

The proposal for a political union of the colonies under one general government in America would be, ultimately, brought into effect by an act of Parliament of Great Britain. However, the colonial commissioners from Massachusetts did not have full powers, so the plan needed to be first submitted to the colonies. The plan was not received unanimously by the colonial assemblies and it was rejected, or failed to ratify (Hutchinson, Mass. III, p.23; Franklin, Writings [ed. Smyth] III, pp. 226-227 n.; R.I. Hist. Tracts, 9; Col. Rec. of Conn. X, p.293).

Reasons for the failure could have been the particularism of the colonies or their underlying conviction that Great Britain would be forced to take on the burden of defending them if left with no other alternative.

All the Assemblies in the Colonies have, I suppose, had the Union Plan laid before them, but it is not likely, in my Opinion, that any of them will act upon it so as to agree to it, or to propose any Amendments to it. Every Body cries, a Union is absolutely necessary, but when they come to the Manner and Form of the Union, their weak Noddles are perfectly distracted.

Franklin, Writings (ed. Smyth) III, P. 242

The colonies action to reject the Albany Plan was decisive. It was understood between the colonies and the British government that the plan was to be submitted to Parliament only after its study and adoption by the colonial legislatures (Report of Board of Trade to King, 29 October 1754. Am. and W.I. 604). It also included a special condition that no copy would be sent to England (Hopkins, A True Representation of the Plan Formed at Albany [Providence, 1755], R.I. Hist. Tracts, 9, pp.42-43. Cf p.39). Nevertheless, to the surprise of the colonies, they discovered a full account of the proceedings for the Albany Congress was sent to England by DeLancey (29 October 1754), but, on 9 August 1754, the Board of Trade also sent a detailed report of the Plan of Union to Sir Thomas Robinson (Am. and W.I. 604; B.T. Plant. Gen. 43, pp. 368-397).

It was recommended that circular letters be sent to the governors in the continental colonies, emphasizing the danger they were exposed to from French encroachments and the urgency for an immediate union of several colonies in order to maintain forts, raise soldiers, defray costs from Indian presents, and the placement of Indian affairs under one general management.

Each colonial assembly was to appoint a commissioner, subject to approval by the governor. They would meet and agree upon necessary military establishments for the colonies during times of peace, including the allocation of expenses among various colonies according to population, trade, wealth, and revenue. Provisions would be made to reconvene the inter-colonial assembly for sudden emergencies, i.e., an actual invasion, that would require greater military operations.

The Crown would appoint a commander-in-chief over all colonial forces and over all troops sent to the colonies from Great Britain upon any emergency. This officer would act as commissary general for Indian affairs. He would also be authorized to call upon the appropriate colonial authority in each colony for money that was already determined as their share of the whole.

The convention drawn upon these lines by the colonial commissioners would be sent to England for approval. However, in order for a convention to be accepted, seven colonies were relegated to constitute a quorum and the decision of this majority would be binding.

The purpose of this plan was to increase military strength in the colonies and make them provide for additional forts on the frontier, as well as presents for the Indians. These gifts were necessary in order to appease the Indians during their ominous state of affairs. And it was not meant for the Crown to lessen its previous expenditures for such purposes, nor refuse aid to the colonies for exceptional emergencies such as war with France.

This plan from the Board of Trade differed fundamentally from the one designed at Albany. This plan considered only a military union, while Franklin and his associates created a blueprint for a political and military union. But the Albany Congress and the Board of Trade began from the premise that the colonies should, in fairness, provide their own regularly-fixed military system.

The failure of the colonies to adopt a plan of union in 1754 forced the English to take action for their defense. The Board recommended the appointment of a commander-in-chief over all colonial and British forces in America, including a position for a commissary general for Indian affairs (B.T. Plant. Gen. 43, pp.368-397). The Board of Trade also proposed in its report on the Albany Plan to create their own regular Indian administration to be supported by Parliament, and that Sir William Johnson would be assigned as colonel of the Six Nations along with the management of Indian relations and their dependent tribes chiefly because of his experience and great influence with the Indians.

Clamoring for assistance was Virginia, but the other colonies showed little or no desire to answer her appeal. The British government responded by adopting the Board of Trade recommendations and sending Major-General Edward Braddock as commander-in-chief to America with two regiments.

Now the British government was reluctant to provide the entire cost for these troops, so, on 26 October 1754, Sir Thomas Robinson, on behalf of the British government, sent letters to the colonial governors telling them to supply fresh provisions for the troops when they arrived from Europe, furnish the officers with a way to travel by land, and to obey the commander-in-chief’s orders regarding the quartering of troops, including the driving of carriages, etc. And since these were local and separate expenses, the colony was to fulfill them. General expenses, such as taxing of troops, would be paid from a common fund already established in the colonies until a general plan of union could be accomplished (N.J. Col. Doc. VIII, Part II, pp.17-19; N.Y. Col. Doc. VI, pp. 915-916; Col. Red. Of No.Ca. V, pp. 144; N.J. Col. Doc. VIII, Part II, pp. 92-93; N.Y. Col. Doc. VI, p. 934).

Meanwhile, plans for a union were not abandoned in America or England even though support was lacking from some colonies to Braddock. It did, ultimately, underscore the necessity of a union, unless, of course, the mother country was willing to assume an unequal share of the burden of the imperial defense.

The colonies total rejection of the Albany plan showed conclusively that a union would never be formed of their own accord, which meant that the Board of Trade’s plan had no chance of success. Inevitably, the only recourse for England was to take it to the sovereign legislature of the Empire and for Parliament to create the union.

When the Board of Trade submitted its plan in 1754, the plan addressed the issue of a union refusal by one or more of the colonies. Could have been either the failure to send representatives from the colonies or, after the plan’s enactment, a refusal to raise the required money. The Board of Trade then will be forced to apply “an application for an interposition of the Authority of Parliament” (Am. and W.I. 604; B.T. Plant. Gen. 43, pp. 368-397).

The two great champions for a parliamentary union in America were Benjamin Franklin and William Shirley, even though their ideas for a union differed fundamentally (Shirley to Robinson, 24 Dec. 1754. N.Y. Col. Doc. VI, pp.930-931). However, the burden of such a union was legally within the power of Parliament, but a statute of this nature would have been in direct violation of the colonial charters and proprietary grants. Such a step was in direct opposition to the colonies intentions and, thus, it would defeat its own purpose to secure the cooperation from the colonies in the event of an impending conflict with France.

A parliamentary union of the colonies, particularly a purely military type, contained within it the concept of parliamentary taxation of the colonies (Shirley to the Board of Trade, 5 Jan. 1756. B.T. Mass. 74 Hh 68). Legally, Parliament could impose a tax but had refrained from doing so, and this disclosure in 1754 was considered by many the only way to compel the colonies to properly support their own defense.

the albany congress plan of union

10 July 1754

Plan of a Proposed Union of the Several Colonies of Masachusets-bay, New Hampshire, Coneticut, Rhode Island, New York, New Jerseys, Pensilvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, For their Mutual Defence and Security, and for Extending the British Settlements in North America.

That humble Application be made for an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain, by Virtue of which, one General Government may be formed in America, including all the said Colonies, within and under which Government, each Colony may retain its present Constitution, except in the Particulars wherein a Change may be directed by the said Act, as hereafter follows.

President General

That the said General Government be administered by a President General, To be appointed and Supported by the Crown, and

Grand Council

a Grand Council to be Chosen by the Representatives of the People of the Several Colonies, met in their respective Assemblies.

Election of Members

That within — Months after the passing of such Act, The House of Representatives in the Several Assemblies, that Happen to be Sitting within that time or that shall be Specially for that purpose Convened, may and Shall Choose Members for the Grand Council in the following Proportions, that is to say.

Massachusetts Bay—7

New Hampshire—2

Connecticut—5

Rhode Island—2

New York—4

New Jersey—3

Pennsylvania—6

Maryland—4

Virginia—7

North Carolina—4

South Carolina—4

48

Place of First Meeting

Who shall meet for the first time at the City of Philadelphia, in Pensilvania, being called by the President General as soon as conveniently may be, after his Appointment.

New Election

That there shall be a New Election of Members for the Grand Council every three years; And on the Death or Resignation of any Member his Place shall be Supplyed by a New Choice at the next Sitting of the Assembly of the Colony he represented.

Proportion of Members After First 3 Years

That after the first three years, when the Proportion of Money arising out of each Colony to the General Treasury can be known, The Number of Members to be Chosen, for each Colony shall from time to time in all ensuing Elections be regulated by that proportion (yet so as that the Number to be Chosen by any one Province be not more than Seven nor less than Two).

Meetings of Grand Council

That the Grand Council shall meet once in every Year, and oftner if Occasion require, at such Time and place as they shall adjourn to at the last preceeding meeting, …

Call

…or as they shall be called to meet at by the President General, on any Emergency, he having first obtained in Writing the Consent of seven of the Members to such call, and sent due and timely Notice to the whole.

Speaker

That the Grand Council have Power to Chuse their Speaker, and shall neither be Dissolved, …

Continuance

…prorogued nor Continue Sitting longer than Six Weeks at one Time without their own Consent, or the Special Command of the Crown.

Member’s Allowance

That the Members of the Grand Council shall be Allowed for their Service ten shillings Sterling per Diem, during their Sessions or Journey to and from the Place of Meeting; Twenty miles to be reckoned a days Journey.

Assent of President General, His Duty

That the Assent of the President General be requisite, to all Acts of the Grand Council, and that it be His Office, and Duty to cause them to be carried into Execution.

Power of President and Grand Council – Peace and War

That the President General with the Advice of the Grand Council, hold or Direct all Indian Treaties in which the General Interest or Welfare of the Colony’s may be Concerned; And make Peace or Declare War with the Indian Nations. That they make such Laws as they Judge Necessary for regulating all Indian Trade.

Indian Purchases

That they make all Purchases from Indians for the Crown, of Lands not within the Bounds of Particular Colonies, or that shall not be within their Bounds when some of them are reduced to more Convenient Dimensions.

New Settlements

That they make New Settlements on such Purchases, by Granting Lands in the Kings Name, reserving a Quit Rent to the Crown, for the use of the General Treasury.

Laws Governing Them

That they make Laws for regulating and Governing such new Settlements, till the Crown shall think fit to form them into Particular Governments.

Raise Soldiers &c. Lakes

That they raise and pay Soldiers, and build Forts for the Defence of any of the Colonies, and equip Vessels of Force to Guard the Coasts and Protect the Trade on the Ocean, Lakes, or Great Rivers; …

Not to Impress

…But they shall not Impress Men in any Colonies, without the Consent of its Legislature.

Power to Make Laws Duties &c.

That for these purposes they have Power to make Laws And lay and Levy such General Duties, Imposts, or Taxes, as to them shall appear most equal and Just, Considering the Ability and other Circumstances of the Inhabitants in the Several Colonies, and such as may be Collected with the least Inconvenience to the People, rather discouraging Luxury, than Loading Industry with unnecessary Burthens.

Treasurer

That they may a General Treasurer and a Particular Treasurer in each Government, when Necessary, And from Time to Time may Order the Sums in the Treasuries of each Government, into the General Treasury, or draw on them for Special payments as they find most Convenient; …

Money How to Issue

Yet no money to Issue, but by joint Orders of the President General and Grand Council Except where Sums have been Appropriated to particular Purposes, And the President General is previously impowered By an Act to draw for such Sums.

Accounts

That the General Accounts shall be yearly Settled and Reported to the Several Assembly’s.

Quorum

That a Quorum of the Grand Council impower’d to Act with the President General, do consist of Twenty-five Members, among whom there shall be one, or more from a Majority of the Colonies.

Laws to be Transmitted

That the Laws made by them for the Purposes aforesaid, shall not be repugnant but as near as may be agreeable to the Laws of England, and Shall be transmitted to the King in Council for Approbation, as Soon as may be after their Passing and if not disapproved within Three years after Presentation to remain in Force.

Death of President General

That in case of the Death of the President General The Speaker of the Grand Council for the Time Being shall Succeed, and be Vested with the Same Powers, and Authority, to Continue until the King’s Pleasure be known.

Officers how Appointed

That all Military Commission Officers Whether for Land or Sea Service, to Act under this General Constitution, shall be Nominated by the President General But the Approbation of the Grand Council, is to be Obtained before they receive their Commissions, And all Civil Officers are to be Nominated, by the Grand Council, and to receive the President General’s Approbation, before they Officiate; …

Vacancies how Supplied

…But in Case of Vacancy by Death or removal of any Officer Civil or Military under this Constitution, The Governor of the Province, in which such Vacancy happens, may Appoint till the Pleasure of the President General and Grand Council can be known.

Each Colony may defend itself on Emergency

That the Particular Military as well as Civil Establishments in each Colony remain in their present State, this General Constitution Notwithstanding. And that on Sudden Emergencies any Colony may Defend itself, and lay the Accounts of Expence thence Arisen, before the President General and Grand Council, who may allow and order payment of the same As far as they Judge such Accounts Just and reasonable.

***

References

Bateson, Mary, ed. A Narrative of the Changes in the Ministry 1765-1767: Told by the Duke of Newcastle in a Series of Letters to John White, M.P. Royal Historical Society. Longmans, Green, and Co., 1898.

Beer, George L. British Colonial Policy 1754-1765. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1907.

Dupuy, Colonel R.E. and Colonel T.N. Dupuy. An Outline History of the American Revolution. Harper and Row, Publishers, 1975.

Franklin Papers. Proceedings of the Albany Congress, 19 June 1754-11 July 1754. National Archives.

Gipson, Lawrence H. The Coming of the Revolution. New York Harper Torchbooks, 1853. p.68.

Gough, Barry M. British Mercantile Interests and the Peace of Paris. University of Montana, 1966. p.49.

Hull, Charles H. and Harold W.V. Temperley. Debates on the Declaratory Act and the Repeal of the Stamp Act, 1766. American Historical Review, 1912, vol. 17, no. 3. Library of Congress.

Labaree, L. W. Benjamin Franklin and the Defense of Pennsylvania, 1754-1757. The Papers of Benjamin Franklin; American Philosophical Society and Yale University. Pennsylvania Historical Association, 1961.

Labaree, Leonard W., ed. The Albany Plan of Union, 1754. The Benjamin Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 5, July 1, 1753-March 31, 1755. Yale University Press, 1962. National Archives.

Labaree, Leonard W., ed. Reasons and Motives for the Albany Plan of Union, July 1754. The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 5, July 1, 1753, through March 31, 1755. National Archives. Yale University Press, 1962. pp. 397–418.

Newbold, Robert C. The Albany Congress and Plan of Union of 1754. Vantage Press, 1955.

Pitt, William Collection. Series I: Correspondence 1758-1806; Series II: Other Papers 1760-1785. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library: Archives at Yale. William Pitt Collection

Price, Richard. Two Tracts on Civil Liberty: The War with America, and The Debts and Finances of the Kingdom – with a General Introduction and Supplement. London, 1778. Printed for T. Cadell in the Strand.

Saltonstall Family Papers. Hutchinson at the Albany Conference. The Correspondence of Thomas Hutchinson, vol. 84; The Correspondence of Thomas Hutchinson, vol. 1, 1740-1766. Colonial Society of Massachusetts: Massachusetts Historical Society.