- Post Contents -

JOHN PAUL JONES: FOREWORD

The legend of John Paul Jones – who was the man behind the folklore? He was a Scot emigrant and a naval combat hero who served and fought as an American during America’s Revolutionary War. His nickname was ‘Terror of the Seas” by those who served with him and by the enemy who fought against him. And he was remembered as a hero in many frightful legends; admired and envied by some of the most respected world courts.

Since childhood, a life at sea was inevitable for John Paul Jones. It was his passion, and he was determined to join the merchant service so he could focus on learning seamanship and naval discipline. This choice in direction prepared him to be ready for a command of his own ship and crew. He developed amazing skills in maneuvering his vessels during enemy engagements and these were, perhaps, the most commendable over his daring ambition and courage.

“It is singular that during the first years of the American navy, with the exception of Paul Jones, no man of any talent is to be found directing its operations. Had it not been for the exertions of this individual, who was unsupported by fortune or connexion, it is very probable that the American naval power would have gradually disappeared.”

Life of Paul Jones from Sherburne’s Collections, London, Murray, 1825

An American naval force was clearly a necessity during the new nation’s independence among the colonies; however, its initial design came through a man who was sent “to aid” America. He fought for his adopted country, the land of his new friendships and affections. This man was John Paul Jones, a man of peculiar character but undeniably capable of great challenges and achievements. He owned an underlying, personal magnetism that was intent and attractive. And under the new American flag, he became a force upon the seas striking terror along foreign coasts while building a reputation of honor he never lost.

“I was indeed born in Britain; but I do not inherit the degenerate spirit of that fallen nation, which I at once lament and despise.’

“…America has been the country of my fond election from the age of thirteen, when I first saw it. I had the honour to hoist with my own hands the flag of freedom, the first time it was displayed on the Delaware, and I have attended it with veneration ever since, on the ocean.”

Commodore John Paul Jones Letter to Baron Vander Capellan, Dutch Minister, ~1788 | J.S.C. Abbott, The Life of Rear-Admiral John Paul Jones, 1874

JOHN PAUL JONES: AMERICAN REVOLUTIONARY WAR, NAVAL COMBAT HERO

The legendary Commodore John Paul Jones died in Paris, France, during the French Revolution. He was 45 years old. He died alone in his apartment on 18 July 1792.

Though John Paul Jones was not known to be a religious man, he was regarded as a Protestant of the Church of Scotland and, thus, the French Assembly instructed his burial be in a Protestant cemetery outside of Paris. According to historical archives, John Paul Jones was buried in a Protestant cemetery, St. Louis Cemetery, outside the French capital. At that time, the cemetery was the property of the French royal family but, after many years, France’s revolutionary government sold the cemetery and, ultimately, it was long forgotten.

Then in the early 1890s, the United States wanted to bring back the body of John Paul Jones but they needed to locate his missing remains. General Horace Porter, the American Ambassador to France, led the search to find the hidden cemetery, excavate the casket, and return the body of John Paul Jones to the United States.

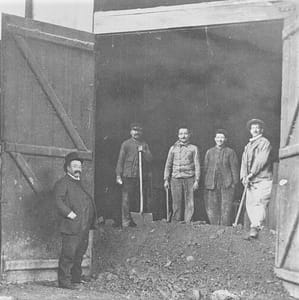

1905-Horace Porter (center), American Ambassador to France, initiator of the search for the body of John Paul Jones, with Mr. Laurent, Secretary General of the Prefecture of Police (left), and Colonel. A. Bailly-Blanchard, Second Secretary of the American Embassy (right), at the excavations at the Cemetery of St. Louis, in 1905. (Courtesy of Horace P. Mende, Kusnacht, Switzerland, 1973, now in the collections of the U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command) | navytimes.com

In 1905, after five years of searches, surveys, and archaeological excavations, the site for the original St. Louis Cemetery was finally discovered, but not until after General Porter’s workmen dug shafts and tunneled underneath numerous streets, shops, and shanties throughout portions of a changed and sprawling city of Paris. Finally, they unearthed their first lead casket but this one proved not to be Jones. Likewise, the second lead casket had a metal plate inscribed with another person’s name other than John Paul Jones. The third casket exhumed had a deteriorating wood exterior but a lead coffin was seen inside that was once of quality and workmanship, suggesting a strong possibility this may be the legendary naval hero, John Paul Jones.

1905-Workmen at site of shaft A for the John Paul Jones disinterment. (Courtesy of Horace P. Mende, Kusnacht, Switzerland, 1973, now in the collections of U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command) | navytimes.com

The archaeological team agreed to move the lead coffin to a better ventilated site before examining the body. After relocation, they found raising the coffin’s lid problematic because of its airtight seal, which was to prevent moisture and retard decomposition of the body. The lid was slowly removed and, at once, a potent odor of alcohol emerged from the coffin. They saw the body enshrouded in a winding sheet of cloth with Jones’ initials stitched in thread, and packed securely with straw. Archaeologists measured the body and the resulting measurement was very close to the five-foot, five-inch known height of John Paul Jones. They carefully took off the winding sheet from the head and chest exposing the face, and discovered the corpse was remarkably well-preserved with its flesh intact, though slightly contracted. Facial features were examined and compared for identification – such as forehead, brow, high cheekbones, and eye-orbit size. The team concurred this was the body of Commodore John Paul Jones and it was now time for a thorough scientific examination.

1905 – John Paul Jones disinterment, photographed 11 April 1905 following the autopsy. (Courtesy of Horace P. Mende, Kusnacht, Switzerland, 1973, now in the collections of U.S. 1905 – Naval History and Heritage Command) | navytimes.com

For safety reasons, the body of John Paul Jones was transported during the night to the University of Paris, School of Medicine, where the medical staff performed a complete autopsy and forensic analysis. Attending the autopsy were French government officials and the U.S. Ambassador to France, General Horace Porter.

According to The Order of the Founders and Patriots of America, the autopsy of John Paul Jones revealed that his death was caused by renal affliction, complicated by pneumonia. His abdominal organs were intact, then removed and examined. Gallbladder and stomach were also there. The kidneys were well‑preserved; however, remains of harmful bacteria were found that led to Jones’ kidney inflammation and pneumonia. At that time, Jones was diagnosed with Bright’s Disease, named after British physician, Richard Bright.

Dr. Richard Bright (1789-1858) | Portrait engraving-H. Cook | britannica.com

“A finding in the autopsy of John Paul Jones, the American Revolutionary War naval hero, may explain his terminal illness. During his last 2 years, he had a persistent productive cough and dyspnea. Ten days before death, he developed rapidly progressive dependent edema and ascites. He died in France in 1792. His body, preserved in alcohol in a lead coffin, was, in 1905, removed to the United States. Glomerulonephritis was noted on an autopsy, performed in France, but there was no comment then or since about ventricular wall thickness being the same in both ventricles at 5-6 mm. Hypertrophy and dilatation with biventricular failure followed by tissue shrinkage during 113 years in alcohol could have resulted in these ventricular wall findings. Systemic hypertension and left ventricular failure are consistent with his respiratory symptoms complicated perhaps by pulmonary emboli, right ventricular failure with tricuspid regurgitation, peripheral congestion, and jaundice.”

-2015 American Academy of Forensics Sciences-

J Forensic Sci. 2016 Mar;61(2):540-544. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.12971. Epub 2015 Oct 29. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26513205

On 24 July 1905, the corpse of USN Captain/Commodore/Admiral John Paul Jones was brought back to the United States and his casket carried ashore at Annapolis, Maryland, by the naval tug Standish. John Paul Jones’ remains were temporarily placed in a vault until the new U.S. Naval Academy Chapel’s construction was completed. Finally, on 26 January 1913, Jones was put to rest in the new crypt of the Naval Academy Chapel.

The crypt was designed by Beaux-Arts architect Whitney Warren, and the 21-ton sarcophagus and surrounding columns of black and white Royal Pyrenees marble were the work of sculptor Sylvain Salieres. The sarcophagus is supported by bronze dolphins and is embellished with cast garlands of bronze sea plants. Inscribed in set-in brass letters around the base of the tomb are the names of the Continental Navy ships commanded by John Paul Jones during the American Revolution: Providence, Alfred, Ranger, Bonhomme Richard, Serapis, Alliance and Ariel. American national ensigns (flags) and union jacks are placed between the marble columns.

https://www.usna.edu/PAO/faq_pages/JPJones.php | United States Naval Academy

John Paul Jones, 1747-1792 | U.S. Navy, 1775-1783| He Gave Our Navy Its Earliest Traditions Of Heroism And Victory | Erected By The Congress, A.D. 1912

Set in brass in the marble floor at the head of the sarcophagus is the inscription:

“Important historic objects related to Jones’ life and naval career are exhibited in niches around the periphery of the circular space. Visitors today at the Naval Academy can see an original marble copy of the Houdon portrait bust, the gold medal awarded to Jones by the Congress in 1787, the gold-hilted presentation sword given by Louis XVI of France and Jones commission as Captain, Continental (U.S.) Navy, signed by John Hancock. Here, too, is a plaque to Ambassador Porter, who was responsible for repatriating the great naval leader.”

https://www.usna.edu/PAO/faq_pages/JPJones.php | United States Naval Academy

JOHN PAUL JONES: HIS EARLY YEARS

Boy Sailor, Successful Seaman, American Patriot

Born John Paul on 6 July 1747, near the shores of Solway Frith, south of Dumfries at Arbigland estate in the parish of Kirkbean, and stewartry of Kirkcudbright in Scotland. The site for Arbigland estate was a green plateau among the mountains that naturally sloped upward from the rugged Solway shore.

Shortly before John Paul’s father, John Paul, Sr. (1700-1767), started the landscaping service at Arbigland estate, he married (1733) Jean Duff (b.~1710), daughter of a family of free landholders and long residents of the county. From this marriage came seven children – William, the eldest (1735[?]-1774); Janet (1739-1817), wife of William Taylor, watchmaker in Dumfries; Mary Ann (1741-1825), married Robert Young (mariner from Whitehaven) then to Mark Lowden ([Louden] originally – farmer of the Stank, Ruthwell, Dumfriesshire, then, in 1777, emigrated with Mary Ann to Charleston, South Carolina [according to James Mackay in his 1998 biography of John Paul Jones’ life]); John Paul (1747-1792); and three other siblings who died in infancy: Elizabeth(?), Jean(~1749), and one unknown.

Originally, the family were long residents in the shire of Fife but John Paul Sr.’s father moved to the town of Leith and ran a tavern that included a market garden. His sons, John Paul Sr. and George Paul, inherited the tavern from their father but they were more interested in being gardeners. They were experienced in designing visual, distinctive landscapes that improved and embellished the natural features on estates. They each declined the tavern, and found employment as professional landscape gardeners on separate estates – Arbigland and St. Mary’s Isle. Master landscape gardeners were highly respected in Scotland, and it offered the Paul brothers a step-up in their social status and gave them respect, which enabled them to develop a friendship with their estate employers. John Paul, Sr. was employed by William Craik, who was landowner of the Arbigland estate – a country squire, and a member of the British Parliament. John Paul, Sr., remained at Arbigland until his death in October 1767.

Whether at St. Mary’s Isle or Arbigland Estate, John Paul’s childhood was spent close to the sea. The nearby shores of the Solway Firth easily roused his boyhood yearning for the seaman’s life. At Arbigland, he watched for hours the tides pitch along the Solway and the big ships in the distance sail mightily on the Irish Sea. He saw across the Irish Sea’s inlet, the English mountains called Helvellyn, Skiddaw, and the Saddleback, and daydreamed of adventurous exploits, but it was the lure of the sea that summoned him. His secretly wandered to the port at the mouth of the River Nith where he listened to mariners from distant lands tell their exciting and perilous seafaring tales. John Paul was mesmerized. He committed to memory the mariners’ words to command a ship and after he returned to Arbigland, he shouted those same commands to his imaginary sailing ships.

John Paul’s Early Voyages

At the age of twelve, John Paul was sent away from Solway Frith across the bay to Whitehaven, England. Whitehaven was once an important seaport for shipbuilding, sailcloth, and rope yards. Whitehaven exported coal, lime, freestone, alabaster, and grain, while importing produce from the West Indies, America, and Baltic. Flax and linen came from Ireland, and pig-iron from Wales. It was there in Whitehaven that John Paul was apprenticed to Mr. Younger, who was a reputable merchant in the American trade and a local resident of Whitehaven.

John Paul’s first voyage was aboard the British merchant brig Friendship of Whitehaven with Captain Benson, which was bound for the Rappahannock in Virginia for a cargo of tobacco. It was not a large vessel, approximately 80 to 85 feet by 22 feet, but hardy upon the seas. As a member of its crew of 28, John Paul learned to handle her sails and 18 deck guns. He also learned the necessity of guns for merchant ships, since they were prize targets for pirates and enemy nations.

John Paul worked on the Friendship sailing annual triangle voyages from Whitehaven to Barbados to Virginia. Consumer goods were shipped to Barbados and exchanged for rum and sugar. In Virginia, rum and sugar were traded for tobacco, pig-iron, and barrel staves. The Friendship also shipped its share of slave victims to the West Indies where they were sold. Frequently, the Friendship anchored near Fredericksburg, Virginia, where John Paul would disembark to visit his elder brother, William Paul, who had married and settled there as a skilled tailor.

John Paul had a strong fondness for America since his childhood, and staying in the Virginia colony tempted his youthful imagination to seek the various opportunities open to daring exploits. However, John Paul knew intuitively that his career was to command a ship and during his apprenticeship years in Virginia and Scotland, he studied hard learning navigation and French. At the same time, he knew the importance of building a solid reputation for discretion, reason, and loyalty in all his duties, which would establish for him trust and honor. These qualities would greatly benefit him in the years to come.

After America’s French and Indian War ended, England’s economy fell into a recession causing Mr. Younger’s business to fail, disabling him to meet his financial commitments. The ship Friendship was sold and the its crew disbanded. John Paul was released from his apprenticeship, leaving him free to act for himself. He decided to contact the Duke of Queensbury for assistance since they had met when he was a young lad exploring the gardens on St. Mary’s Isle estate, while the Duke was visiting his brother-in-law, the fourth Earl of Selkirk.

The Duke recommended him to a commander in the Royal Navy, who appointed John Paul as an acting midshipman aboard a British Man-of-War. He remained in this position for a short time, but long enough to understand that family interest had more influence than personal merit. He watched junior midshipmen be promoted while he was ignored. This action made John Paul more determined to join the merchant service and take with him the valuable experience he acquired, including the intimacy he developed with “many officers of note in the British Navy” – a reference John Paul used in his later letter (4 September 1776) to Robert Morris regarding the organization of the American navy.

Another reference that John Paul used during this same time period was from a paper written in 1783 for Robert Morris stating he had “sailed before this revolution in armed ships and frigates.” Such statements inferred that John Paul knew the rules. The training of British naval officers with such information would be invaluable for the drilling of inexperienced colonial seamen for the first flagship (letter to Joseph Hewes, 19 May 1776) of the first American fleet.

After John Paul left the Royal Navy, he obtained another post as third mate on the slaver King George at Whitehaven, which was bound for the Guinea Coast of Africa for slaves. Then in 1766, John Paul was made chief mate aboard the brigantine Two Friends, of Kingston, Jamaica. This quick advancement to a higher position proved that John Paul was a skilled mariner, responsible, and reliable. It became apparent that the ship Two Friends also dealt in the same ruthless slave trade as the King George and sailed to the same West India islands, including the coasts of Africa and Spain. John Paul was forced to witness the cruel and dirty business of slave trafficking, and he was never able to understand the justification of such a trade that came from the enslavement of human beings, growing large fortunes in Liverpool and Glasgow, the Caribbean, and the British colonies of America.

In 1768, after two years on the slave ship, John Paul hated it so much that he abandoned his position while in port in Jamaica. He was now alone and unemployed. He wanted to return to Scotland but needed to wait for passage on another ship and eventually found passage on the brigantine ship, John, of Kirkcudbright. During the voyage, there was an outbreak of yellow fever and both Captain MacCadam and his first mate died from the fever. Since it was determined that there was no one else in the crew capable of commanding the ship, John Paul took charge and brought the ship safely into port. Because of his resolve and confidence to take command, the ship’s owners, Currie, Beck, & Company – West India merchants and residents of Kirkcudbright – offered John Paul an opportunity to be appointed master and supercargo (i.e., officer in charge of ship’s cargo) for the John. This position made a young John Paul responsible for the owner’s cargo trade – selling merchandise in designated ports and buying and receiving goods for the return voyage.

John Paul sailed two round-trip voyages with the crew of six men on the John to the West Indies. However, during the spring of 1770, while John Paul supervised the unloading of his ship’s cargo from Scotland and the loading of more cargo onto the vessel at Tobago, he was confronted with a unruly sailor. This sailor, Mungo Maxwell, was listed on the ship’s log as carpenter and was reported as lazy, disrespectful to his commander, and mutinous. John Paul appropriately tried to contain the sailor, but was unsuccessful. Then in order to preserve his authority, John Paul found it necessary to enforce physical punishment against the man. At the time, the standard practical code of a ship’s discipline on a delinquent was flogging; a practice used by the British and American mercantile marine service. This action, unfortunately, resulted in serious complications and difficulties for John Paul.

“Paul as this deponent is informed, has been accused in Great Britain as the immediate author of the said complainant’s death, by means of the said stripes hereinbefore mentioned.’

“This accusation, this deponent, for the sake of humanity, in the most solemn manner declares and believes to be in his judgment without any just foundation as far as relates to the stripes before mentioned; which this deponent very particularly examined, and

Further this deponent saith not.’

“James Simpson.’

Sworn before me, this 30th day of June, 1772 WILLIAM YOUNG.”

Life and Correspondence of John Paul Jones; From Original Letters and Manuscripts in the possession of Miss Janette Taylor, 1880. Pp.19.

After returning to Scotland from Tobago on the John in the late 1770s, John Paul visited the port of Kirkcudbright for a short time and while there, he submitted a letter for his application of admission to the lodge of Freemasons – John Paul Jones received his E.A. Degree in St. Bernard’s Kilwinning Lodge No. 122, Kirkcudbright, St. Mary’s Island, Scotland on November 17, 1770. His letter was later preserved in fac-simile in Douglas Castle, Saint Mary’s Isle (masonicfind.com). Also while in Kirkcudbright, John Paul Jones learned that Currie, Beck & Company dissolved their partnership and he was, once again, unemployed.

Mungo Maxwell pressed charges against John Paul before James Simpson – a judge of a Vice-Admiralty court, which was in session at the time in Tobago – and made a complaint. The judge examined Mungo’s flogging stripes and found them to be insignificant, whereby Maxwell’s complaint was dismissed as frivolous.

“James Eastment, mariner, and late master of the Barcelona packet, maketh oath, and saith, that Mungo Maxwell, carpenter, formerly on board the John, Captain John Paul, master, came in good health on board his, this deponent’s said vessel, then lying in Great Rockley Bay, in the island of Tobago, about the middle of the month of June, in the year one thousand seven hundred and seventy, in the capacity of a carpenter, aforesaid; that he acted as such in every respect in perfect health for some days after he came on board this deponent’s said vessel, the Barcelona packet, after which he was taken ill of a fever and lowness of spirits, which continued for four or five days, when he died on board the said vessel, during her passage from Tobago to Antigua. And this deponent further saith, that he never heard the said Mungo Maxwell complain of having received any ill usage from the said Captain John Paul; but that he, this deponent, verily believes the said Mungo Maxwell’s death was occasioned by a fever and lowness of spirits, as aforesaid, and not by or through any other cause or causes whatsoever.”

“James Eastment.’

“Sworn at the Mansion House, London, this 30th of January, 1773, before me, James Townsend, Mayor.”

Life and Correspondence of John Paul Jones; From Original Letters and Manuscripts in the possession of Miss Janette Taylor, 1880. Pp.20.

“Before the Honourable Lieutenant-Governor, William Young, Esq. of the island aforesaid, personally appeared James Simpson, Esq. who, being duly sworn upon the Holy Evangelists of Almighty God, deposeth and saith, That some time about the beginning of May, in the year our Lord on, thousand seven hundred and seventy, a person in the habit of a sailor came to this deponent (who was at the time Judge Surrogate of the Court of Vice-Admiralty for the island aforesaid) with a complaint against John Paul, (commander of a brigantine then lying in Rockley Bay of the said island,) for having beat the then complainant, (who belonged to the said John Paul’s vessel,) at the same time showing this deponent his shoulders, which had thereon the marks of several stripes, but none that were either mortal or dangerous, to the best of this deponent’s opinion and belief. And this deponent further saith, that he did summon the said John Paul before him, who, in his vindication, alleged that the said complainant had on all occasions proved very ill qualified for, as well as very negligent in, his duty; and also, that he was very lazy and inactive in the execution of his, the said John Paul’s lawful commands, at the same time declaring his sorrow for having corrected the complainant. And the deponent further saith, that having dismissed the complaint as frivolous, the complainant, as this deponent believes, returned to his duty. And this deponent further saith, that he has since understood that the said complainant died afterwards on board of a different vessel, on her passage to some of the Leeward Islands, and that the said John Paul (as this deponent is informed) has been accused in Great Britain as the immediate author of the said complainant’s death, by means of the said stripes herein before mentioned, which accusation this deponent, for the sake of justice and humanity, in the most solemn manner declares, and believes to be, in his judgment, without any just foundation, so far as related to the stripes before mentioned, which this deponent very particularly examined. And further this deponent saith not.’

“James Simpson.’

“Sworn before me, this 30th day of June, 1772, William Young.”

Life and Correspondence of John Paul Jones; From Original Letters and Manuscripts in the possession of Miss Janette Taylor, 1880. Pp.20.

Another unexpected turn came from a troubling announcement that Mungo Maxwell had died on a Barcelona ship shortly after John Paul sailed back to Kirkcudbright. John Paul was blamed for Maxwell’s death. The rumor was improbable, but it was found to have been spread from Maxwell’s relations and they threatened to have John Paul arrested. Added to his worry, he became troubled by the jealousy from his neighbors and shipmates, who openly resented his quick rise to commander. John Paul couldn’t convince them the rumor from Maxwell was false. His family felt humiliated because of the rancorous rumor and he was saddened to find that his trusted patron, Mr. Craik, had also believed the false rumor.

LONDON, 24th September 1772.

MY DEAR MOTHER AND SISTERS: —

“I only arrived here last night from the Grenadas; I have had but poor health during the voyage, and my success in it not having equalled my first sanguine expectations, has added very much to the asperity of my misfortunes, and I am well assured was the cause of my loss of health. I am however better, and I trust Providence will soon put me in the way to get bread, and (which is far my greatest happiness) be serviceable to my poor but much valued friends. I am able to give you no account of my future proceedings, as they depend upon circumstances which are not fully determined.’

“I have enclosed you a copy of a affidavit made before Governor Young by the Judge of the Court of Vice Admiralty at Tobago, by which you will see with how little reason my life has been thirsted after, and which is much dearer to me, my honor, by maliciously loading my fair character with obloquy and vile aspersions. I believe there are few who are hard hearted enough to think I have not long since given the world every satisfaction in my power, being conscious of my innocence before Heaven, who will one day judge even my Judges. I staked my honor, life and fortune for six long months on the verdict of a British Jury, notwithstanding I was sensible of the general prejudices which ran against me; but after all, none of my accusers had the courage to confront me. Yet I am willing to convince the world, if reason and facts will do it, that they have no foundation for their harsh treatment. I mean to send Mr. Craik a copy of properly proved, as his nice feelings will not perhaps be otherwise satisfied. In the meantime, if you please, you may show him the enclosed. His ungracious conduct to me before I left Scotland I have not yet been able to get the better of; every person of feeling must think meanly of adding to the load of the afflicted. It is true I bore it with seem unconcern, but Heaven can witness for me that I suffered the more on that very account. But enough of this!”

– Letter from John Paul to his family, 24 September 1772 –

Life and Correspondence of John Paul Jones; From Original Letters and Manuscripts in the possession of Miss Janette Taylor, 1880. Pps. 19-20.

Sometime after the incident, William Craik reconsidered his judgment of John Paul as he grew more convinced of Paul’s innocence. John Paul’s loyalty and support for his valued friends were highly regarded, and it was agreed by his peers that it was unnecessary for him to provide further evidence of his innocence against the unjust charges. However, John Paul remained unconvinced with the written evidence he received from Judge Simpson, which was obtained from James Eastment – captain of the ship on which Mungo Maxwell died – that the charges against him had been resolved.

“James Eastment mariner and late master of the Barcelona Packet, maketh oath and saith that Mungo Maxwell carpenter formerly on board the John, Captain Paul, Master, came in good health on board his, this deponent’s said vessel, then lying in Great Rockley Bay, in the island of Tobago, about the middle of the month of June in the year one thousand seven hundred and seventy, in the capacity of a carpenter aforesaid.’

“That he acted as such in every respect in perfect health for some time after he came on board this deponents said vessel, the Barcelona Packet after which he was taken ill of a fever and lowness of spirits, which continued for four or five days, when he died on board the said vessel during her passage from Tobago to Antigua.’

“And this deponent further saith that he never heard the said Mungo Maxwell complain of having received any ill usage from the said Mungo Maxwell’s death was occasioned by a fever and lowness of spirits as aforesaid, and not be or through any other cause or causes whatsoever.”

John Paul’s affidavit testifying to the then Lord Mayor of London, on the 30th of January, 1773

William Craik had a son, James Craik, who ventured to America without his father’s approval to cast his support with the colonists’ cause of British opposition. Though this son of Craik was born illegitimate, William Craik publicly acknowledged him as his son, James, and, thus, was well cared for and educated. When the son moved to America, it disappointed his father greatly, but his son became the distinguished Dr. James Craik who served closely with George Washington as Assistant Director General of the Middle Department of the Continental Army in 1774. After the war, he later moved on to a private medical practice in Alexandria, Virginia, visiting Mount Vernon often as George Washington’s friend and personal physician until Washington’s death in 1799.

Captain John Paul – Fugitive from Justice

The next command (1770-1771) came under the recommendation from the ship owners of the John, when John Paul took charge of the three-masted, 22 gun-mounted British brigantine, Betsey, of London – a vessel engaged in the West India trade. Although the Betsey was a leaky ship, Captain John Paul made the best of it. He focused on his business and profits, but the crew was heard grumbling over a non-resolved wage issue. In 1773, while in port at Tobago, John Paul claimed his crew mutinied. The ringleader, whom John Paul described as a “massive brute of thrice his strength,” menacingly approached John Paul and swung a club at him. Captain John Paul immediately responded in self-defense by lunging his sword into the ringleader. John Paul’s friends urged him to take leave of the island quickly because the dead assailant was a Tobago native, and the local authorities would probably not give John Paul a fair hearing. He took their advice and fled the island, leaving behind considerable Tobago property he acquired from various commercial speculations. John Paul entrusted his property to agents with whom he was familiar in Tobago, but, unfortunately, he later discovered he was betrayed by those same agents and all his property gone.

John Paul turned up in Fredericksburg, Virginia, in 1774, to reunite with his brother, William, when he learned William had died. William Paul was buried in 1774 in a grave close to Faulkner Hall just inside the front gate and to the left at St. George’s Episcopal Church, Fredericksburg, Virginia.

[NOTE: there were sources that claimed William Paul died without a will, yet I found there was a pre-existing will – specifically in Spottsylvania County, Virginia, witnessed on 16 December 1774, by John Atkinson and John Walker, Jr. | heritage-history.com]

The story continues … Part 2 … forthcoming

Comment

It was difficult finding and verifying reliable information on John Paul (Jones) on various aspects of his life. A good example is his surname change to ‘Jones’. Some sources reported a theory of when John Paul could have added his new surname – such as when he escaped from Tobago – when he learned the British regarded him as nothing more than a pirate and fugitive, so, intentionally, he concealed his identity. Possible, I suppose, but I could not confirm without supporting documents. Two additional theories agreed that John Paul assumed the new surname of ‘Jones’ when he arrived in Virginia in 1774. These may be possible, but the assumptions are presently unconfirmed.

Then I came across another ‘Jones’ mention from a claimed biographical sketch on John Paul Jones by a Dr. Duncan of Scotland for the Edinburgh Encyclopaedia (18 volumes; printed and published by William Blackwood and edited by David Brewster between 1808 and 1830). I found a list of five, named Duncan as contributors for the Encyclopaedia and only one was a possible author for that biography – a Very Reverend Henry Duncan DD FRSE – Scottish minister, geologist, and social reformer / Minister of Ruthwell parish church in Dumfriesshire (south of Dumfries was the estate of Arbigland where John Paul was born). Anyway, Dr. Duncan wrote that it was custom to take the father’s Christian name or a paternal ancestor’s name and affix a derivative word to the name base. However, this custom was not common within the proximity of John Paul’s birthplace but it was common in Wales, the Isle of Man, and other surrounding areas that John Paul frequented. Again, not enough supporting documentation to support this theory.

Here’s the last theory, or should I say rumor, that I will entertain regarding the mystery of the ‘Jones’ name change. It has an interesting backstory, I will admit, but I couldn’t find any solid evidence to its authenticity. So here it is: North Carolina had an old story circulating as part of its pre-revolutionary war history as to why John Paul added ‘Jones’ to his name. John Paul met the Jones brothers, Willie (pronounced Wylie) and Allen, while he was wandering in North Carolina during his period of depression in 1774. The brothers were quite wealthy as well as slave landowners from their father, Robert Jones, who was reported to be the colonial agent for the estates of Lord Granville of North Carolina. Both brothers quickly befriended John Paul, and they graciously offered the hospitality of their large homes as a place to stay and restore his health. And it was at Willie Jones’ estate, as it was rumored, that John Paul met Willie’s inner circle of politically, influential friends and where John Paul found himself in the center of Revolutionary activity. After the hospitality with the Jones’ brothers, it seemed John Paul added ‘Jones’ to his name – most likely in respect to his hosts.

Whatever John Paul may have done during his absence from public view when he was depressed … or for whatever reason, it created a frenzy of speculation from various gossipers from private to public. Yet, there were no corroborative documentations that I could find which could verify such claims. And I have not recovered any reasonable answers from my searches that would solve ‘why’, John Paul added the surname ‘Jones’, but with it he was honored anyway and well-remembered.

References

Abbott, J.S.C. 1874. The Life of Rear-Admiral John Paul Jones. New York: Dodd & Mead, Publishers, Fair Haven, Conn.

Arbigland Estate – John Paul Jones

kirkbean.org

British History Online / Whitehaven

british-history.ac.uk

De Koven, R. 1913. The Life and Letters of John Paul Jones. Volume: 1. Contributors: Reginald De Koven – Author. Publisher: C. Scribner’s Sons. Place of publication: New York. Publication year: 1913

questia.com

Encyclopedia.com. Updated 2019. Jones, John Paul

encyclopedia.com

Extracts from the Journals of Paul Jones Campaigns

https://www.americanrevolution.org/jpj.php

Hampton, Ellen. 2019. When John Paul Jones Crossed Over. Military History Magazine

navytimes.com

John Paul Jones. 1880. Life and Correspondence of John Paul Jones, including his Narrative of the Campaign of the Liman. From Original Letters and Manuscripts: in the possession of Miss Janette Taylor. Stereotyped by A. Chandler, New York

archive.org

Jones, John Paul. Life and Correspondence of John Paul Jones, Including His

Narrative of the Campaign of the Liman. From Original Letters and Manuscripts in the Possession of Miss Janette Taylor. Ed. by Robert C. Sands. New York: D. Fanshaw, 1830.555 pp.

Life of John Paul Jones. 2017. John Paul Jones Birthplace Museum Trust. Dumfries Museum

jpj.demon.co.uk

John Paul Jones: Genealogy. 2008. Dumfries Museum

jpj.demon.co.uk

Naval History and Heritage Command. 2019. John Paul Jones

history.navy.mil

Naval History and Heritage Command. 2015. John Paul Jones: Unpublished biography

history.navy.mil

Reiss, W.C. 1987. The Ronson ship: The study of an eighteenth-century merchantman excavated in Manhattan, New York in 1982. University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars’ Repository; Doctoral Dissertations.

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c302/53f2b026291f786ff02364c4812bcab9e671.pdf

https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2526&context=dissertation

United States Naval Academy. John Paul Jones: Public Affairs Office

usna.edu