A new archaeological site in Alaska unearthed prehistoric human remains discovered by scientists in North America. The site was an ancient fire pit within an ancient dwelling in Upward Sun River near the Tanana River in central Alaska. The skeletal remains appeared to belong to a three-year-old child cremated some 11,500 years ago. Radiocarbon dating of the wood at the burial site coincided with that date, which was about the same time that the Bering land bridge probably still connected Alaska with Asia. Testing on the child’s teeth confirmed a biological connection with Indigenous Americans and Northeast Asians…

Scientist Ben Potter and archaeological team

Photo: Ben Potter | inverse.com

- Post Contents -

prehistoric human – discovery update

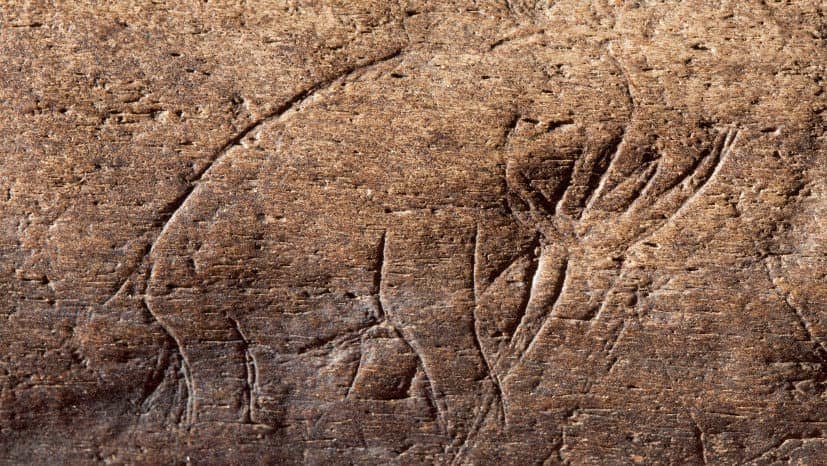

Five years later – 2013 to 2018 – the prehistoric human remains unearthed in 2013 at the Alaskan archaeological site of Upward Sun River were now found to also contain two ice age female infants. The two babies were discovered together approximately 15 inches below the same 11,500-year old firepit where the first three-year old child was unearthed. Skeletal and dental analyses indicated that Infant-1 died shortly after birth and Infant-2 was a late-term fetus. Also uncovered with the two infants were grave offerings of shaped stones and antler foreshafts decorated with incised lines. These offerings are some of the oldest compound weapons found in North America, and making these the youngest-aged late Pleistocene individuals known for the Americas.

Image: Potter et al. 2014 (www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1413131111)

Researchers suggested the deaths of the three children within the group may had been facing food shortages. “The deaths occurred during the summer,” researchers said, “…a time period when regional resource abundance and diversity was high and nutritional stress should be low, suggesting higher levels of mortality than may be expected given our current understanding [of survival strategies at that time-ibtimes.co.uk].”

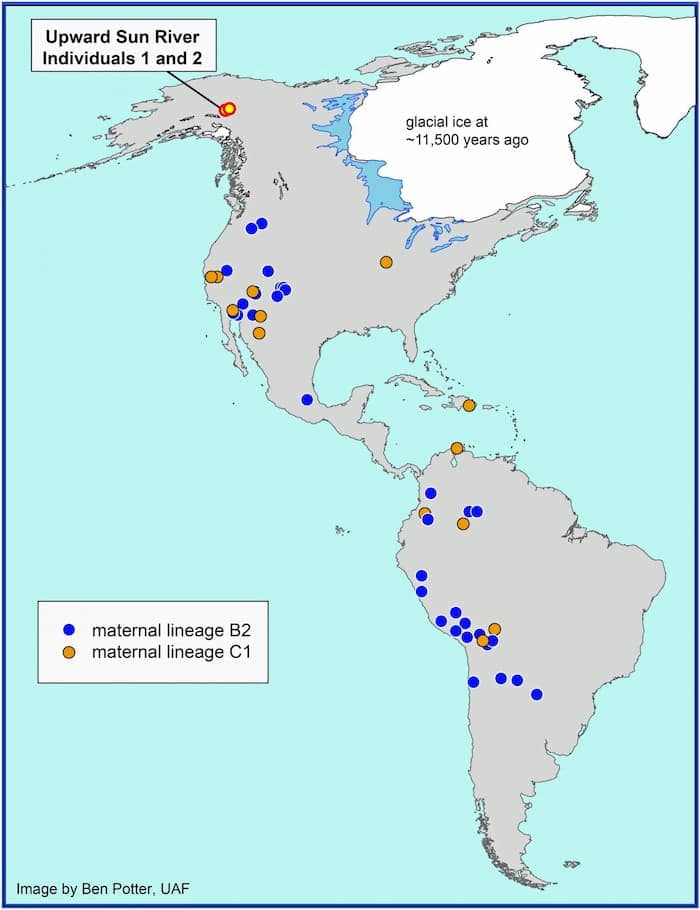

Unlike the older child that was found cremated, the two infant remains were sufficiently preserved to allow DNA analysis. Scientists then recovered adequate genetic material from one of the infants’ bones and were surprised to find some unexpected determinations about how prehistoric humans arrived in North America.

Illustration by Eric S. Carlson in collaboration with Ben A. Potter. | sites.google.com

ancestral populations

(adapted from Moreno-Mayar, Potter, et al. 2018)

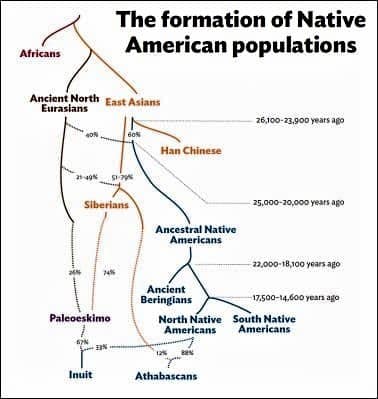

A full genome was classified by scientists on one of the female infants, and it was revealed that the female belonged to a once unrecognized Indigenous American people called Ancient Beringians. According to the scientists from the Universities of Cambridge and Copenhagen, the infant’s genes are considered evidence that Ancient Beringians were the first to arrive in North America and, because of that, it’s reasoned they were the primary descendants of the ancestral people that preceded present-day northern and southern Indigenous American people. José Victor Moreno Mayar, Ph.D., of the University of Copenhagen remarked, “One could think of Ancient Beringians as a third branch of Native Americans, the other two being North and South Native Americans.”

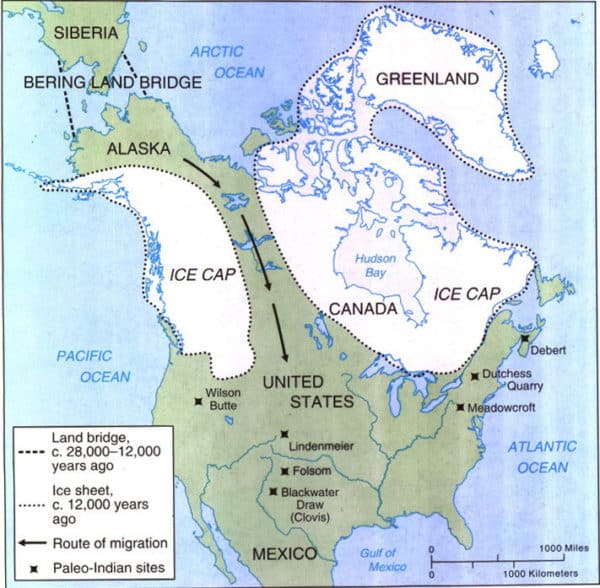

The study suggested that the beginning population of Indigenous Americans separated from an ancestral Asian group in northeast Asia approximately 36,000 years ago during the Late Pleistocene era. These Indigenous Americans then migrated across the Beringia land bridge that once connected northeast Asia to northwestern North America. They encountered harsh weather and glacial barriers that kept some of the people – probably Ancient Beringians – immobile for long periods of time. Eventually, the split occurred between the North and South Indigenous Americans after their people were capable of passing through the thawing, giant glaciers that covered Canada and parts of the northern United States.

Much has been learned about the lifeways of the Ancient Beringian through the research at the Upward Sun River site. Evidence of their hunting large game of bison and elk, small mammals like hare and ground squirrels, as well as birds came from the excavations at a residential camp at the Upward Sun River site. Significant findings of salmon use were also evident. Patterns of complex land use as a logistical operation was readily identified from the Upward Sun River, Gerstle River, and other sites as well as organized hunting parties, which specialized in megafauna (e.g., bison), processing the meat at spike camps (e.g., Gerstle River), then returning to centrally-located residential base camps (e.g., Upward Sun River) with the meat. Foraging for small game and fish were also done at these residential camps. Such versatile plans were remarkably flexible especially in the Subarctic through its various climate and vegetation changes over 6,000 years.

PREHISTORIC HUMAN ROUTE – BERINGIA PASSAGE

This land bridge (Beringia) extended north and south for thousands of miles, covering an area that is now the Bering Strait and its surrounding seas. This glaciation provided a passage from Asia to North America for humans and migrating animals. It is estimated that this land bridge existed for several thousand years at different times, and it is believed that hunting bands from Asia pursued ice age migrating herds across Beringia reaching Alaska. Once in Alaska, these first American hunters and their descendants, continued to follow the big-game animals of the Pleistocene Age along ice-free routes of the Alaskan coasts, through the Yukon and river valleys. They moved south of the glaciers to Central and South America as well as to the Atlantic Coast. Archaeological finds verified the existence of Homo sapiens in much of North and South America some 13,000 years ago; however, some were also now found to be earlier.

PREHISTORIC Human FORAGERS

Until about 12,000 to 11,000 years ago, our ice-age emigrants were all foragers that depended on wild food for sustenance. They were skilled hunters, killing megafauna like the mammoth, mastodon, elk, and large bison as well as smaller animals. They fished and gathered shellfish, insects, wild fruits, vegetables, tubers, seeds, and nuts. Prehistoric stone tools and animal bones recovered from archaeological hearths of emigrant camps suggested the lack of knowledge for farming.

discovermagazine.com

discovermagazine.com

The foraging culture demanded an expansive land area approximately 7 to 500 square miles for their food supply, and they had to move whenever this supply depleted. Individual bands usually were small in number, typically no more than 30, because larger groups of people quickly exhausted the area’s food resources. Their housing were simple huts, tents, or lean‑tos because they needed to be transported on foot to the next region. Each band was tied to other groups through kinship over a wide area, and often that network of groups assembled for short periods each year.

Paleo-Indians

The Clovis people (9,050-8,800 BC), named for the New Mexico site from which they were found, were once thought to be the first inhabitants of the New World. Their tools were well known for their characteristic “fluted” flint point that could pierce the skin of a mammoth. Originally, they were considered by science as the ancestor to all natives of North and South America (Paleo‑Indian).

Photo by Charlotte D. Pevny – Courtesy Michael R. Waters

mdpi.com

The Folsom culture of North America (9,000-8,000 BC), first found in 1908 at Folsom, New Mexico, excavated in 1926, was also known for their projectile “fluted” flint points. Like the earlier Clovis culture, they too were considered Paleo-Indian, big-game hunters and gatherers. Most of the Folsom artifacts have been found throughout the Great Plains.

However, recent discoveries in Oregon, Alaska, Texas, Washington, and California proved that humans existed in North America 2,500 years earlier than already believed. In Oregon, a team of researchers found small spearheads and hunting tools along with human feces in the Paisley Cave complex that dated back approximately 13,000 years ago. From an archaeological dig in Washington, another team of researchers used a bone point fragment from an ancient mastodon rib, which confirmed hunters roamed North America about 800 years earlier than previously believed. Scientists in Texas have unearthed from an archaeological dig at Buttermilk Creek, stone tools and other ancient artifacts dating back 15,500 years, making this site the oldest settlement ever found in North America.

Numerous artifacts, including stemmed projectile points and crescents, have been uncovered by researchers in three sites on California’s Channel Islands. These artifacts interpret a story of a sea‑based culture among its inhabitants from 12,200 to 11,400 years ago. Tools and remains of animals from 12,000 years ago have been uncovered on islands off the coast of California that described a culture of superior tool technology as well as a marine economy.

Proto-Indian

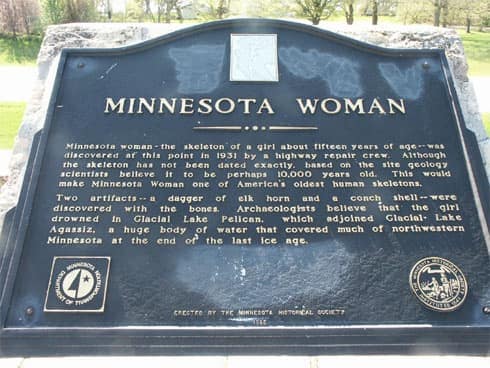

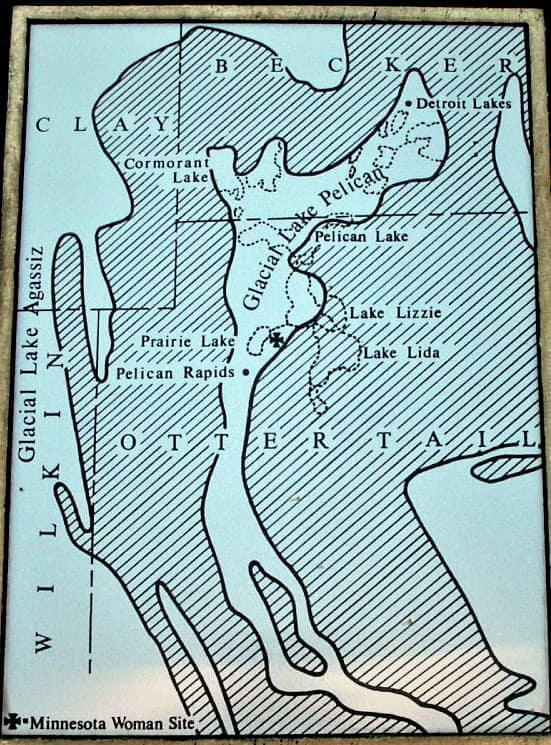

In June 1931, a highway repair crew were working at leveling earth with a grader blade near Pelican Rapids in Otter Tail County, Minnesota, when they discovered a human skull. The crew carefully unearthed the skull and surrounding bones from layers of silt, sand, and putrefied shells, which were either clam or mussel. The bones, along with a conch shell pendant and an elk’s horn dagger, were sent to the University of Minnesota.

The examination of the human remains revealed that the pelvic bone belonged to a young, mature female who had never experienced childbirth. Her burial site also shows that this “Minnesota Woman” was not formally buried, but rather suffered a death by drowning in a glacial lake.

This information perplexed researchers because there had been no water in the burial area for approximately 10,000 years. And at that time, Glacial Lake Pelican was formed by melted arctic ice that combined all the lakes in the Pelican River Chain, including some higher ground. It also bordered Glacial Lake Agassiz, which was at that time, the largest glacial lake. Scientific evidence suggested that the “Lady of the Lake” was Proto-Indian – a race of humans who lived very near the glaciers at the end of the Pleistocene Ice Age.

Cochise Culture

In the south from Arizona and western New Mexico, the Cochise culture existed about 9,000 to 2,000 years ago and was named for the ancient Lake Cochise, which is now a dry desert basin called Willcox Playa. They were a desert culture of gatherers, collecting wild plant foods and not much hunting. Initially (7,000 or 6,000 BC to 4,000 BC), they were found to have used various scrapers and milling stones for grinding wild seeds, but there were no knives, blades, or projectile points found. Although some animal remains were uncovered, it is assumed that some hunting was done. Then from 4,000 to 500 BC, projectile points appeared indicating an increase in hunting as well as traces of a primitive maize that suggested the beginnings of farming. From 500 BC to AD, mortars and pestles replaced the milling stones. The Cochise culture has been noted as the basis for other developing cultures that followed.

Commentary

After writing the piece about Mammoth Cave, I grew curious about the prehistoric Indigenous American of North America. Since I’ve always had an interest in archaeology, researching and writing the article was like excavating my own revelations of these long-buried first North Americans. Of course, I could only imagine the exciting moment of realization when the scientists and research team uncover remains of a fossil relic, artifact, or organic material, and then discover it to be a key to a mystery or secret from antiquity! However, all I can be is elated over the intellectual stimulation of discovering information I never knew.

Nevertheless, I learned that prehistoric humans were resourceful and skilled. Their tools and weapons proved an ability to think, adapt, and survive in a primitive and dangerous environment. Not only was the extreme weather conditions difficult to endure, but the megafauna they hunted were also an extreme prey to kill. I can’t visualize these prehistoric hunters with primitive weapons hunting mastodons, mammoths, or large bison but they did, and they were successful. It seemed nothing was impossible for them.

They were the New World’s first pioneers. They blazed a trail over a frozen land bridge and moved their clans beyond the horizon – over mountains, down valleys, along seacoasts, and through forests to the east. As hunters and gatherers, they continually moved along their trails, leaving cultures behind. They became a long-forgotten story, but I found them connected to the next ancient culture on the history timeline – the prehistoric Indigenous American farmer.

Updated 2020

References

http://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/12newworld/background/preclovis/preclovis.html

http://www.4shared.com/web/preview/doc/kLUEEM1y

http://universalium.academic.ru/238050/Clovis_complex

http://universalium.academic.ru/263364/Cochise_culture

Jenks, A.E. 1936. Pleistocene Man in Minnesota. Univ. of Minn. Press.

Josephy, Jr., A.M. 1968. The Indian Heritage of America.

Morris, R.B. (Ed.). 1953. Encyclopedia of American History. Harper & Brothers, New York, N.Y.

http://www.sdnhm.org/archive/exhibits/mystery/fg_timeline.html

http://www.nmhcpl.org/First_American.html

http://frontierscientists.com/projects/human-history-science/upward-sun-river/

http://www.wacotrib.com/news/oldest-known-human-habitation-in-the-americas-uncovered-in-salado/article_19d48a28-f62d-51bc-897e-1a379d7ffbbc.html

https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2010/11/12/is-florida-mammoth-the-tip-of-the-iceberg/

https://www.inverse.com/article/39885-first-native-americans-ancient-beringians

https://tennesseearchaeologycouncil.wordpress.com/2014/11/14/late-pleistocene-burials-from-the-upward-sun-river-site

https://sites.google.com/a/alaska.edu/dr-ben-a-potter/ancient-beringians