- Post Contents -

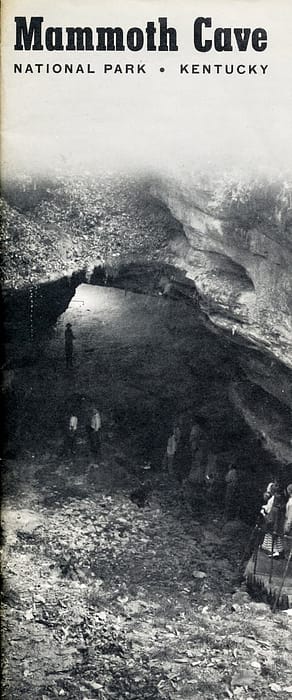

MAMMOTH CAVE NATIONAL PARK, 1965

USDOI-NPS

In the summer of 1965, my family traveled to Kentucky for another camping vacation and my highlight of that trip was Mammoth Cave National Park. Since then, I visited three other caves, Niagara Falls State Park Cave of the Winds, Colorado Springs Cave of the Winds, and New York’s Howe Caverns which was known as Mammoth Cave’s rival in 1855, but none of them left a mark on me quite as impressive as Mammoth Cave.

My adolescent amazement at the sight of the cave’s historic natural entrance took my breath away. Slowly, we descended the long stairway into the dark depth of the cave as the air temperature quickly dropped. It was cold compared to the August heat above ground. As a nine-year old, I believed the constant 54 degrees Fahrenheit was cold enough to preserve a dead body, but, I later discovered it wasn’t cold enough for a morgue or even a refrigerator. I was very glad to have my jacket anyway.

I was an avid book reader in my youth, but I had never heard of Mammoth Cave. This underworld was my own private expedition into a dark unknown, fantasy. An ultimate adventure beyond my wildest imagination. It was such a colossal hole beneath the earth, I didn’t know what to expect. I looked beyond our tour guide and the perimeter cave lights of the Historic Entrance into the blackness of unlit corridors and passages nearby, and I suspected that somewhere in that blackness, lost spelunkers were entombed. It was so exciting.

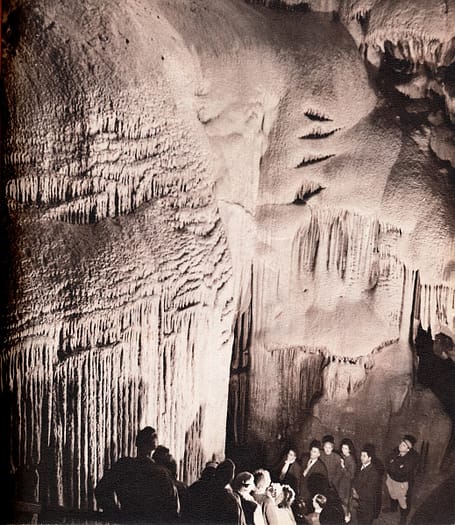

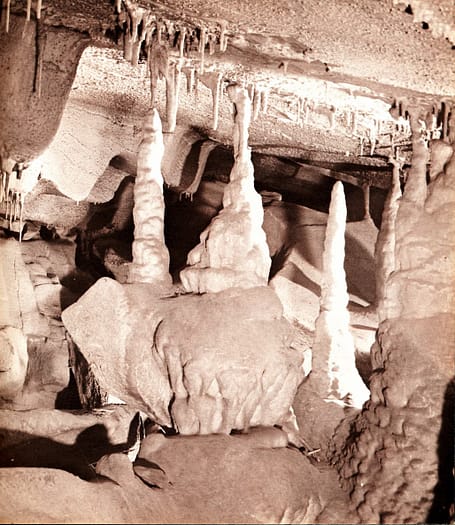

Huge caverns called “great rooms” and spectacular rock formations – dome pits, draperies, dripstone and flowstone, and columns of joined stalactites and stalagmites – all contributed to the cave’s water deposit beauty that had me awestruck and speechless. It fired my curiosity to explore more.

MAMMOTH CAVE HISTORY

Before 2009, Mammoth Cave was considered one of the world’s largest known caves but, by 2013, I found it was officially redefined as one of the longest caves at 400 miles – forward again to 2017, it was increased to 412 miles. Located in south-central Kentucky on the Green River, about 85 miles southwest of Louisville, there is a region of limestone caves that covers approximately 8,000 square miles through the states of Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

Local folklore maintains the story of a regional hunter, John Houchins, who unintentionally found the cave entrance while hunting game. The time frame for this discovery is only approximate because of conflicting dates that continue to remain unconfirmed – either 1798 or 1802. Apparently, Houchins encountered a black bear near the cave’s entrance. He took the opportunity for a kill, aimed his smoothbore, flintlock or Fowler rifle and fired. From here, the legend splits into two possible versions. One offers the possibility that he only wounded the bear and followed the animal’s trail to the cave’s entrance. The other possibility was that Houchins missed his shot and was determined to follow the bear in the hope of getting another shot, when the animal led him to the cave and disappeared inside. Unfortunately, the legend ends here and no more information is known whether Houchins got his bear; however, Houchins continues to be recognized as the modern founder of Mammoth Cave. As you read further along, you’ll find that prehistoric, indigenous American Indians within this region were found to have utilized the cave’s resources over a thousand years ago.

Around the same time local settlers learned of Mammoth Cave, a public record of land surrounding the limestone cave was listed in the Warren County Survey Book, dated 1796-1815. The local settler who posted the first claim was Valentine Simons – “200 acres of second-rate land lying on the Green River,” as well as two “petre caves.” The claim was registered in Warren County, Commissioner Certificate No. 2428, and described as running along the Green River, starting with a sycamore tree running southward, including two petre caves. The two petre caves were Dixon and Mammoth.

Dixon Cave was also discovered by early Kentucky settlers, reportedly in the 1790s. And it was also found to be a valuable source of nitrate sediments – enriched by bat guano – just like its nearby neighbor, Mammoth Cave. Tons of this sediment was also removed from the cave during the War of 1812 for use in gunpowder. In 1810, sightseers began touring the cave and found thousands of bats inside. A newspaper reporter who covered the story referred to the bats being “crowded so close that they resembled a continuous black cloud.” In 1850, Yale biologist Benjamin Silliman, Jr., visited the cave and estimated the number of bats to be in the millions.

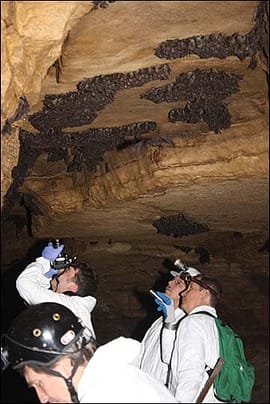

By 1996, park researchers and scientists investigated Mammoth Cave for similar evidence of the bats but not much was found. However, on the rocks of the cave walls and ceilings, scientists discovered reddish stain marks where bats would naturally roost. In other passages within the cave, scientists also discovered bat remains and dated them. Analysis of the bat bones suggested Mammoth Cave was a primary, winter hibernation shelter for Indiana bats, while some gray bat remains indicated the cave’s warmer rooms were favorite summer roosts. Researchers estimated that as many as 20 million Indiana bats may have used the cave’s passages in the past.

Photo by USFWS; Andrew King | fws.gov

In 1993, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) conducted nationwide surveys of the Indiana bat population that showed this endangered bat species had declined 41 percent during the 1980s. Typically, these bats are found inhabiting forest locations along the banks of rivers, lakes, or tidewaters in New England as well as the Midwest during summer. In winter, they seek steady temperatures of 37 to 45 degrees Fahrenheit where they will cluster in large, tight groups containing thousands of individuals, and caves provide this stable environment. Winter after winter, these bats return to the same cave and to the same spot on a cave wall to rest – to reduce their metabolic rate and conserve fat reserves. However, only three percent of all U.S. caves provide these conditions. The majority of Indiana bats were found in Kentucky, Missouri, and Indiana; however, approximately 85 percent of the Indiana bat population hibernated in seven caves – Mammoth Cave National Park being the favorite bat cave.

Unfortunately, in 2006, an illness called White-Nose Syndrome (WNS) was first observed in a New York cave in February 2006 among dead and dying bats. The distinctive “white nose” is a ring of white fungus often visible on the faces and wings of affected bats. This syndrome has killed more than a million bats since 2006, and has spread from the New York caves to other caves and mines throughout the Northeast, Southeast, and Midwest. It continues to spread to the West and Southwest, and has been reported in Washington State. In 2013, the White-Nose Syndrome was found in Mammoth Cave bats, but its effects on the cave and population of bats has yet to be determined.

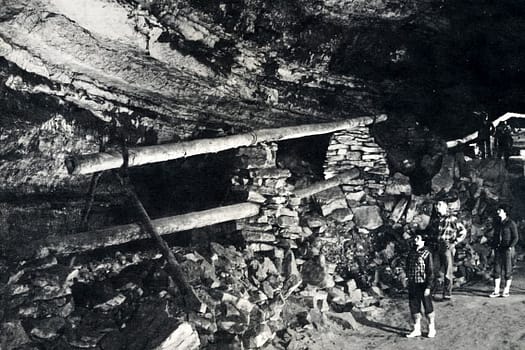

The first tour my family took at Mammoth Cave was the Historic (1.5 miles – 1.5 hours), which started at the Mammoth Cave Historic Entrance and took us to the Rotunda area to see the saltpeter vats from the War of 1812. I learned that saltpeter (potassium nitrate [KNO3]) found in the cave was a major source of nitrate that was needed to make gunpowder during that war. Saltpeter was also very important for caves because it was a source of nutrients for other organisms that lived there.

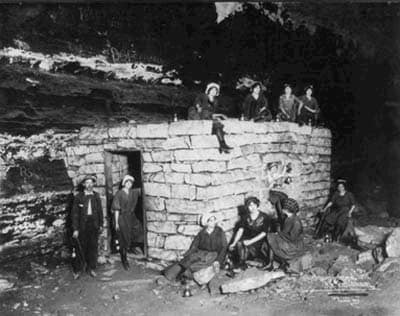

Moving further along the trail, I saw a cave stone statue in the likeness of Martha Washington and then passed by a section called Giant’s Coffin, which I don’t recall what that was and I’m assuming that the eroded limestone had taken on a coffin resemblance. Then our tour came upon two remaining stone buildings called, “consumptive huts,” which were built as an underground tubercular hospital as a research experiment for tuberculosis. The man responsible for that idea was Dr. John Croghan, who bought Mammoth Cave in 1839 from Franklin Gorin for $10,000. Unfortunately, the underground consumptive hospital experiment proved to be a failure and, ironically, Croghan contracted tuberculosis and died in 1849.

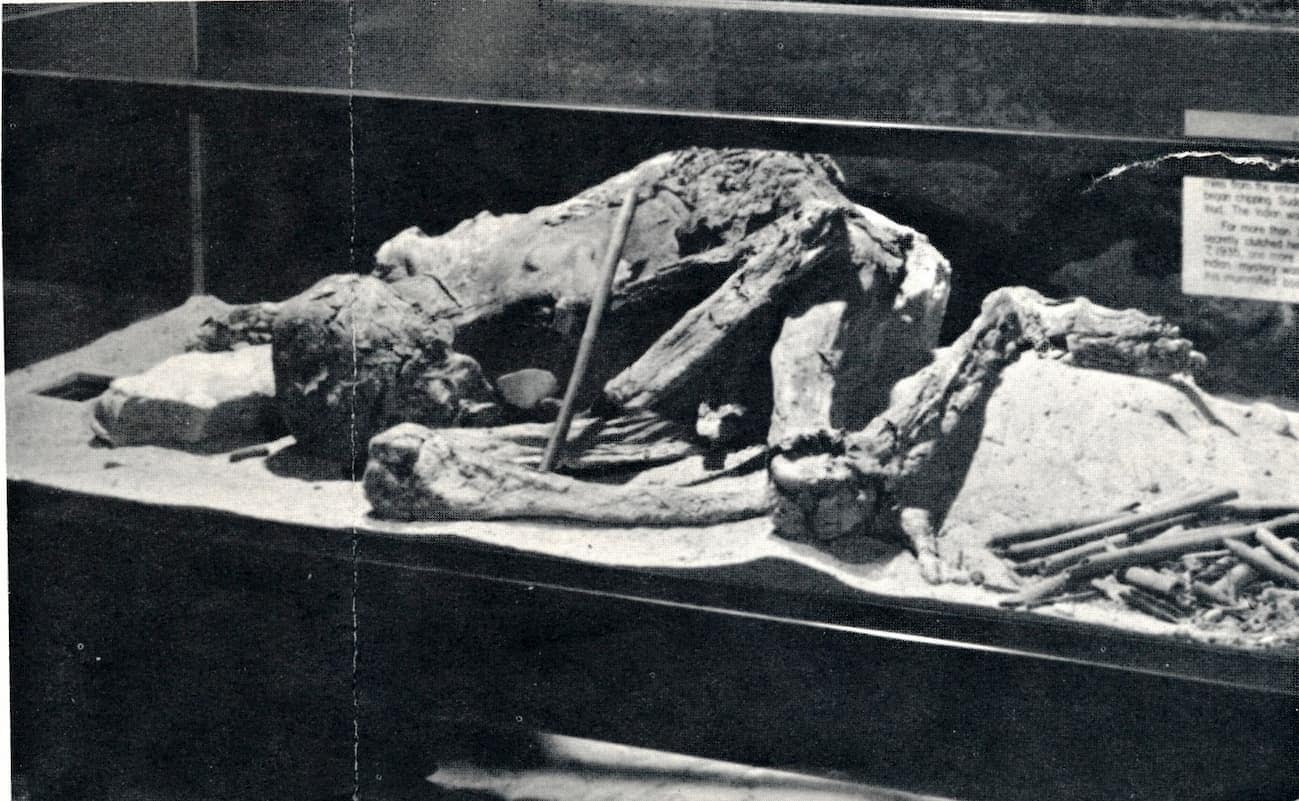

MAMMOTH CAVE PREHISTORIC MUMMY

When I met the male Indian mummy – who I discovered many years later was likely dated from the Late Archaic to the Woodlands periods (1500-2000 BC) of North America’s prehistory – I was amazed and captivated. I was thrilled and humbled at the same time just to be so close to an ancient corpse that was so well-preserved after hundreds of years. I carefully studied the mummy in his glass case from every angle. I knew that I would never forget him. He unknowingly planted in me an unusual interest for archaeology, paleontology, and geology. And since then my interest never faded, only increased toward the science of pathology.

Near the Indian mummy were some of his final, earthly possessions – cane reeds for torches and a woven foot sandal. He wore a woven loincloth and a mussel shell necklace, with skin that still covered his bones – though looking dry and brittle. His nose remained with its nasal bone and septal cartilage, but his eyes and ears were gone. Even his toenails remained. I never knew what a human body looked like in death and he inspired me to consider being an archaeologist; however, I became a writer digging up history instead.

So who was this prehistoric, Late Archaic Indian (1,000 BC to 500 BC) who ventured 2.5 miles into Mammoth Cave to mine gypsum? And why gypsum?

By 1500 BC, the Woodland culture Indian entered Kentucky and settled the area for approximately 600 years. They were skilled hunters and gatherers, and participated in a developed network of trade for materials such as copper from Lake Superior, volcanic glass called Obsidian from the Rocky Mountains, and conch shells from the Gulf of Mexico. They mined both Mammoth Cave and Salts Cave for gypsum, as well as the minerals mirabilite and epsomite for their medicinal, cleansing properties. The Woodland people cultivated corn, sunflowers, giant ragweeds, and amaranth (pigweed), and raising squash and gourds for containers rather than as a food source. The remains of two distinct Woodland groups, the Adena (early Woodland) and the Hopewell (middle Woodland), have been found in north-central Kentucky.

A definitive reason for gypsum mining by these Indians remains unclear. Some historical clues indicated a possibility for a white paint base for rituals, yet other uses may have been a type of salt, diet additive, medicine, or maybe fertilizer. Maybe they used it for toothpaste, or maybe they discovered that gypsum could be ground up and boiled at low temperature, which eliminated most of its moisture and created a fine powder. Maybe the Indians knew they could make a mortar from the powder by adding water – like Plaster of Paris – to form shapes that hardened. Possibly, but I couldn’t find evidence that supported these uses as a part of their culture even though they had limited use of pottery.

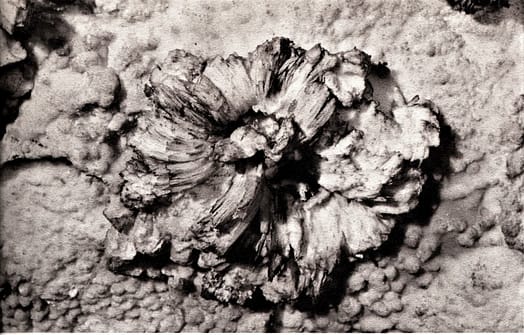

Gypsum naturally forms on rock surfaces as well as on walls and ceilings in Mammoth Cave. As they develop, they push older growths outward into different shapes and form a crust over an entire wall or ceiling. Uneven formations, called “blisters” or “snowballs,” are produced by pressure from behind, and when the “blister” opens, a beautiful, delicate shape is revealed – similar to flower-like petals, a rosette, or a fibrous mound that resembles cotton (see gypsum photo).

This ancient Indian gypsum miner was scraping gypsum from an overhead rock surface that was a 6.5‑ton boulder supported precariously by a small column of rock. The boulder dropped as he was digging into the rock surface. He was thrown from his kneeling position and crushed to death. For several centuries, he remained on his ledge under the rock boulder until he was found in 1935. His mummified body was well preserved by the cave’s cool, steady conditions and has been considered an important archaeological discovery.

According to cave historical records, its first mummy discovered was in 1813, by a man digging for saltpeter in the cave. It was the body of a tall, young Indian woman who was found behind a large flat rock in a burial chamber, seated upright and covered with a blanket. She had dark reddish hair and her hands were held across her chest by a fiber cord. She was buried with some personal possessions that included wrapped deerskins, fabric sandals, a woven knapsack, and a net bag. The knapsack and bag contained a cap, seven feather headdresses, several necklaces – a deer-hoof, an eagle-claw, and a bear-jaw – two rattlesnake skins, deer sinews, bone and horn needles, and two cane whistles.

By the late nineteenth century, other prehistoric Indian artifacts were discovered in the cave by other visiting archaeologists. Such items were a black-and-white-striped cloth, feather blankets, turkey tail-feather fans, baskets, squash-shell cups, raw textile materials, fishing nets, basket coffins of cane, as well as bows and arrows.

MAMMOTH CAVE UNDERGROUND RIVER

The next tour I remembered was the flat-bottom boat trip on the cave’s underground waterway called the Echo River (3 miles / 3 hours). The trail to the river went through the Rotunda, then through a section called Broadway, and again passed the Giant’s Coffin into a lower area of pits and domes. There was a 105-foot bottomless pit, and I remembered squeezing through the winding corridor called “Fat Man’s Misery.” We reached the place called “River Hall,” and the trail moved down to Echo River – 360 feet below the surface.

It was an eerie boat ride. So quiet, with the only light to see by was on the boat. The tour guide spoke of the famous blind fish that was discovered in 1838 in the cave’s river, but I don’t recall having seen any blind fish in the river; however, I remembered the wide‑brim hats and dark uniforms worn by the tour guides.

There were no other trails I remembered that our family toured in Mammoth Cave in 1965, but the photos I’ve seen of the “flowing” travertine rock formations in the area called “Frozen Niagara” looked very familiar. Most likely I saw them in the cave, but I cannot recollect that specific tour.

COMMENTARY

I went back to Mammoth Cave National Park 26 years later with my children, and I was sadly disappointed to learn that the “mummy” I adored was gone. I was told by a tour guide that the reason for removing the Indian mummy to a hidden location within the cave system was due to the decision that his remains would no longer be for public display. And those who made that decision felt there was a lack of respect to the remains as well as to his ancestors. I strongly disagreed with that decision. And I guess the Egyptian museum didn’t feel it was disrespectful to investigate and analyze their mummy ancestors or display them.

If scientists were allowed to examine the remains of the Mammoth Cave Indian mummy, I suspect their analysis would prove just as important as that of the Iceman. Useful DNA information could have been gained from the mummy’s examination determining his ancestral roots.

(continued…)

– CASE-IN-POINT –

Ötzi, the Iceman. A wet mummy that was mummified naturally in glacier ice 5,300 years ago and discovered in the Otztal Valley Alps on 19 September 1991 by two German tourists at an elevation of 10,530 feet (3,210 meters). The discovery site was on a mountain range in the central-eastern region of the Alps bordering southern Austria and northern Italy. Today, the mummy is stored in an icy vault at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, Italy.

I was so excited to hear about the discovery of Ötzi, the Iceman, that I couldn’t wait to meet him, even though it was only by television or print media pictures. I was thrilled to see him and hungry to learn as much as I could about him – very much like it was for me in 1965 with the Archaic Indian mummy from Mammoth Cave.

Scientific examination of his body revealed his age to be approximately 45 years old, and 5 feet (1.60 meters) tall. Most of his body hair was lost during decomposition, but small clumps of hair found on his body were of medium-length and dark. From his DNA, scientists’ found the oldest evidence of Lyme Disease, from his digestive tract they found whipworm eggs (an intestinal parasite), and from his clothes two human fleas. That’s exciting news.

Ötzi’s teeth, bones, joints, internal organs, and tattoos were also probed, but it was the results of his DNA analysis that I thought was the most profound and most valuable for the world today. His genome revealed his genetic ancestry was rare in Modern-Europe but found solely linked to the natives from the islands of Sardinia and Corsica, which were secluded from the mainland of Italy.

Another interesting fact revealed was that Ötzi was murdered. A mystery that perhaps will be solved in the future, but, for now, Iceman was an intriguing find into an ancient, unknown world who cracked a hidden door open into the Copper Age of Europe.

UPDATE (2017) – Ötzi, the Iceman – After much study, archaeologists confirmed Ötzi’s death was indeed violent. There was a head trauma and a deep cut to the bone between his thumb and forefinger. They also carefully examined the arrowhead embedded in his left shoulder and determined it was most likely a fatal wound that caused the Iceman to bleed to death.

Because of the glacier’s preservative properties, Ötzi’s weapons and tools successfully kept their initial shape. His hunting kit, a doeskin quiver along with feather-fletched arrows, is now known as the world’s oldest hunting kit, and it is carefully stored at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Italy. However, what museum researchers discovered among the Iceman’s belongings was the rarest of archaeological finds. It was the Iceman’s bowstring, which was carefully wrapped and stored in his quiver. It too was carefully inspected and found to be made of three strands of animal sinew twisted into a cord. The only other ancient bowstrings recovered from around the world were from Egyptian graves dated from 2200 to 1900 BC, thus, dating the Iceman’s bowstring from 3300 to 3100 BC as the oldest bowstring by a 1,000 years.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (NAGPRA)

When I discovered the NAGPRA, I understood why the Mammoth Cave mummy was reburied in a remote, undisclosed area of the cave. Indigenous American tribes claimed the rights to the remains of lineal descendants, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural items. “The statute requires Federal agencies and museums to provide information about Native American cultural items to parties with standing and, upon presentation of a valid claim, ensure the item(s) undergo disposition or repatriation.” – usbr-gov

As a result of the NAGPRA in 1990, museums and federal agencies were required to return more than 50,000 sets of human remains and a million grave objects to Indian tribes and Indigenous Hawaiian organizations. Even though we are now in a time of major advances in forensics, dating, and DNA analysis, the NAGPRA is urging efforts to adapt scientific interest in most ancient remains – 8,000 years and older – with the approval of the nation’s 567 federally-recognized tribes. However, according to some reports, not all ancient skeletons will face a pending reburial. Factors that influence such decisions would be the where and when discovered, the custodian, and the tribes expressing an interest for its return.

Much of the distrust between Indigenous communities and scientists is not based on facts but emotion. And that’s okay. I now understand the Native American right to claim the ancient, human remains from a tribe’s aboriginal lands. I only wish the Mammoth Cave tour guide in 1991 would have explained the whole reason why. Anyway, it’s their heritage, their tradition and belief, to control and protect the destiny of their ancient remains, and I respect that right. Even though I think some Indigenous groups are sincerely curious, like you and I, in knowing what could be learned from our ancient ancestors. And I’m very glad that I got to meet Mammoth Cave’s Indigenous American.

(…continued)

The Indian Mummy was an important teaching experience for me, and I am sure it was for others as well who witnessed his historic preservation. He was an ancient human whose body introduced me to the world of physical and visual science. That was a big deal for me because I didn’t like science in school. It was boring. But my encounter with Mammoth Cave was an experience that changed my view of science leaving an everlasting, impressionable mark on me. It was “hands‑on” learning, and that was the best approach for me to understand the world of science. There was so much to learn from the cave – geology, hydrology, archaeology, paleontology, natural rock decorations and deposits, and its more than 200 species of animals that inhabited its dark environment.

Our family camping trips during the 1960s to the southern States of Tennessee and Kentucky became invaluable for me. Those vacations provided sense experiences in a natural environment that a school classroom cannot teach; visual, touch, smell, hearing, and sometimes taste.

I’ve read many books in my youth and they were great for reaching into areas where I could not go or I did not know, but they could not compare to the insight and knowledge I received from the historical places I’ve toured. Revisiting these places brought back fond times of an innocent era when my imagination was introduced to a world beyond the descriptive words of a book. It brought back to life lost voices of the past and taught me to relive history through my senses.

References

Ansley, Clarke F. (ed.). 1935. The Columbia Encyclopedia In One Volume. Columbia University Press.

e-ReferenceDesk.com. Kentucky Early History: Kentucky First Inhabitants. 2013.

http://www.e-referencedesk.com/resources/state-early-history/kentucky.html

Construction Dimensions. 1985. Because water will return Gypsum to its Original Rock Form, Gypsum Has Earned Its Reputation as the “Wonder Mineral” in Construction.

http://www.awci.org/cd/pdfs/8503_c.pdf

Kennedy, M.C. Kennedy and P.J. Watson. 1997. The Chronology of Early Agriculture and Intensive Mineral Mining in the Salts Cave and Mammoth Cave Region, Mammoth Cave National Park, Kentucky. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies 59(1): 5-9.

https://caves.org/pub/journal/PDF/V59/V59N1-Kennedy.pdf

Nps.gov. Gold, Grass, and Gypsum. 2013.

Scout, Cav. 2009. Dixon Cave. Geocaching.

https://www.geocaching.com/geocache/GC1YH9B_dixon-cave

South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology -2016.The Mummy. Iceman.

USDOI.NPS. 1965. Mammoth Cave National Park. Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

The Bureau of Reclamation. 2019. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA)

https://www.usbr.gov/nagpra/

Toner, M. 2017. The Fates of Very Ancient Remains. American Archaeology; Vol. 21, No. 2

http://sites.utexas.edu/tarl/files/2017/08/Fates-of-Very-Ancient-Remains.pdf

US Fish & Wildlife Service. Updated 2019. Midwest Region Endangered Species.

https://www.fws.gov/midwest/endangered/mammals/inba/index.html

2013 | Reviewed 2023